3. Freshwater

Aotearoa New Zealand’s freshwater environment supports all aspects of our lives, and we share an intimate connection with it. It is central to our quality of life, supporting the economy, recreation and food-gathering. For many Māori, the freshwater environment is central to customs and protocols (tikanga), knowledge (mātauranga) and traditional food-gathering practices (mahinga kai).

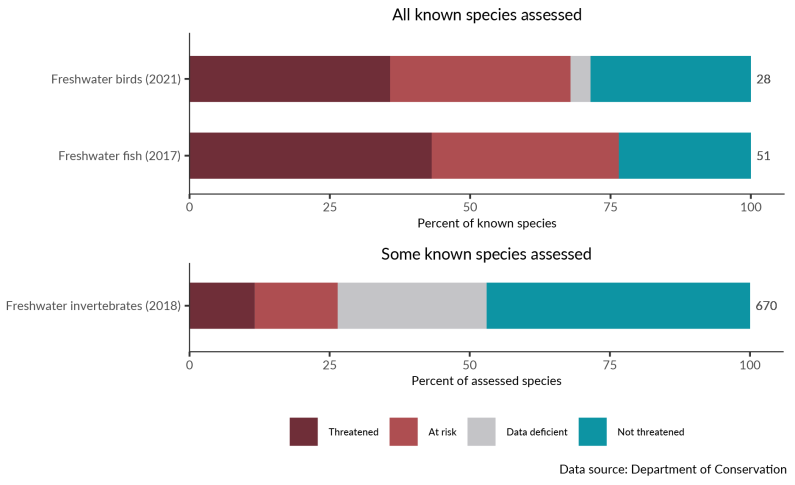

Despite this, freshwater is under pressure from activities on the land and in the water, and from a changing climate. Although some freshwater bodies are in a reasonably healthy state, many have been degraded by the effects of these pressures on water quality and freshwater habitats. Further, most indigenous freshwater fish and freshwater bird species, including some iconic treasured (taonga) species, are either threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened.

Rivers and groundwater act as pathways transporting nutrients, sediments and contaminants from the land to the marine environment. Changes in the quality of freshwater can also affect estuaries and coastal waters (see section 4: Marine).

This section looks at two key issues.

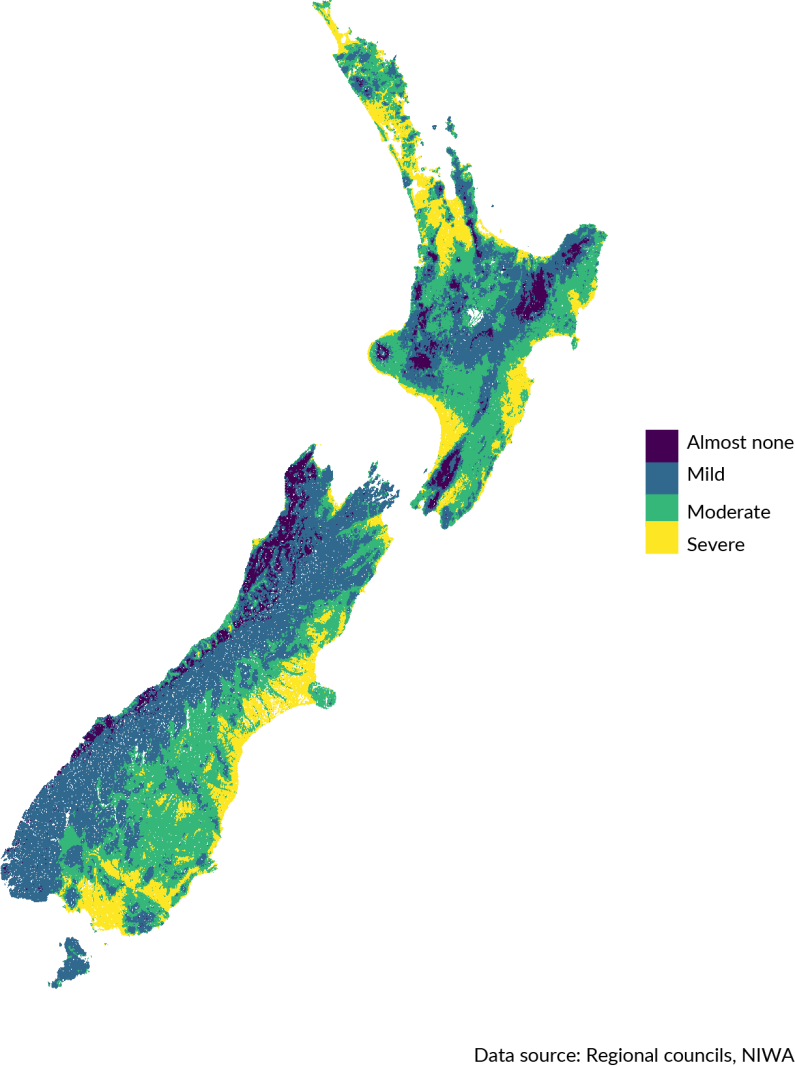

First, it reports on the state of freshwater quality in our groundwater, rivers and lakes. It also summarises the pressures, including agriculture, wastewater and stormwater, which are responsible for the degraded state of many waterways.

It then presents evidence on how freshwater quality, land conversion, changes to flows and water courses, pests and climate change are all affecting the state of freshwater habitats and native species.

For the wider effects of the state of freshwater, see section 7: Impacts on people, society and the economy.

New Escherichia coli (E. coli) monitoring data show that contamination by faecal pathogens remains the most widespread water quality issue affecting groundwaters. Evidence not previously available from water suppliers shows that E. coli levels have failed to meet drinking water standards in some samples from aquifers that supply public drinking water.

An assessment of new nitrate-nitrogen monitoring data has strengthened previous assessments of the scale of nitrate impact in groundwaters. It indicates that a significant proportion of groundwaters have accumulated excess nitrate due to human activities, which can compromise drinking water quality and degrade surface water ecosystems. Groundwaters in most parts of the country continue to comply with drinking water standards, but some aquifers are still not safe for supplying drinking water that has not been treated for nitrate.

New monitoring data for pesticides and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) indicate that they are not widespread in groundwaters, and rarely occur above drinking water standards.

A new model for lake water quality affirms previous assessments that almost half of the country’s lakes are in poor health due to excess nutrients. However, unlike the previous model, it predicts that most of the remaining lakes are in good health, rather than average. This is due to the new model’s improved accuracy for lesser-impacted lakes, and does not reflect a measured change in the state of lake environments between assessment periods.

(See Some river and lake ecosystems are showing signs of degradation from excess nutrient levels.)

The indicator update for indigenous freshwater-dependent birds shows most species remain threatened with extinction, or at risk of becoming threatened.

(See Many indigenous freshwater species are threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened.)

An updated assessment by the Department of Conservation shows a significant proportion of our indigenous freshwater plant species remain threatened with extinction, or at risk of becoming threatened.

(See Many indigenous freshwater species are threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened..)

The quality of our freshwater is affected by different human activities. This impacts the health of ecosystems, and our ability to safely connect with the freshwater environment. This subsection looks at the state of groundwater, lakes and rivers, and what it means for drinking and swimming. It also examines the pressures that can degrade them.

Freshwater quality is widely monitored across groundwater, lakes and rivers, and models are used to predict water quality in unmonitored rivers and lakes. Cultural indicators, such as for traditional food-gathering practices (mahinga kai), can show the overall health of freshwater ecosystems. This subsection uses a selection of these measures to assess the extent of freshwater pollution in New Zealand, focusing on faecal pathogens and nutrients. Elevated nitrogen and faecal contamination can make waters unsafe for drinking, and faecal contamination can make them unsafe for recreation. Excess nutrients can degrade freshwater habitats and ecosystems, and harm freshwater species.

4 Moreau et al (2025) update the information in the current version of the Stats NZ Groundwater quality indicator, published in April 2020. The data from Moreau et al will be incorporated into the next indicator update, but the statistics published in the updated web page may differ due to methodological (or other) differences (see Technical annex).

New Zealand has many unique native species that depend on freshwater. When freshwater quality declines, these species and their ecosystems become threatened. This subsection looks at how pressures such as invasive species, sediment and contaminants, along with changes to water flows from irrigation and hydropower, are affecting habitats and placing some species at risk of extinction.

The effects of climate change are intensifying many of these pressures. This is discussed in section 6: Atmosphere and climate.

5 Note that extinction threat information updated since the Extinction threat to indigenous species indicator update in 2023 has been included in the text and is based on New Zealand Threat Classification System data downloads (see Technical annex; NZTCS, 2025). Figure is based only on information available in the indicator (see indicator: Extinction threat to indigenous species).

3. Freshwater

April 2025

© Ministry for the Environment