Chapter 2: The driving forces

The basics of life – where we choose to live and the food we choose to eat – have an influence on the demand for land and how it is used in Aotearoa New Zealand. Our growing population will continue to drive this demand in the future.

A growing global population increases the demand for timber and food. More people, higher incomes, and changes in behaviour shift the demand for certain goods, causing changes in export markets.

Overseas markets are a significant driver in land use. Most of the products of agriculture and forestry are exported and these activities cover half of our land area.

The impacts of climate change are expected to force people to move from coastal locations and increase demand for housing inland.

Policies on trade, immigration, and housing can also affect how, and how intensively, we use land. The decisions we make today about how to use the land in this country will shape the ability of future generations to meet the demands of their time.

What we choose to eat and where we choose to live flows through to the ways we use land. The quality and price of food and housing, and the location of our housing are important for wellbeing. These essentials make up a large proportion of our expenditure. Housing and household utilities and food accounted for around 40 percent of the average weekly household expenditure for the year ended June 2019 (Stats NZ, 2020a).

Around the world, consumers are becoming more discerning about how the food they buy is produced. Food producers are expected to be transparent about their food growing methods and practices, and this influences industries to adapt their land-use practices to meet the demand (Driver et al., 2019; Journeaux et al., 2017). Land owners can be required to meet certain sustainability standards, including protecting biodiversity, but meeting standards may increase prices and access to markets (Norton et al., 2020).

Passing an exhaustive document audit earlier this year was the last hurdle to full organic certification for Mark and Karen Spooner’s dairy farm. It completes a three-year transition from conventional farming.

“We were thinking about organics, but on a family trip to America we were blown away that what the market over there was screaming out for was grass-fed, traceable, low input milk. It was exactly what we were doing but we weren’t getting full recognition for it”, says Mark. “When we got home we did the numbers and realised that organic production captured that and stacked up from a business perspective – it had to.”

Researching the organic option involved visits to local organic dairy farms, which Mark confesses he imagined would be full of weeds and look unkempt.

“I didn’t want to have a farm where it looked like the land was going backwards, but these were beautiful – I couldn’t believe it. There were trees and shady areas, and the cows could eat everything that was growing, even the feijoa hedges. That was a game-changer for me.”

The Spooner’s farm comprises 110 hectares of prime dairying land near Te Aroha in Waikato. Mark grew up on the farm, which was bought by his grandparents in 1944. Today he and Karen milk 260 cows.

“Under a conventional system it was about trying to get the most out of the land. After we bought the farm from my parents we pushed the numbers up to 340 for financial reasons. That’s what I thought stewardship was. Now I see myself more as a caretaker than an owner.”

Mark says animal welfare and soil health are foundational to organic farming because backups like antibiotics are off-limits.

“As soon as something doesn’t look quite right, you have to act on it. But we rarely have vets or lame cows on the property now. Our soils were compacted and anaerobic, but aerating them solved so many problems – it got rid of the buttercup and the mud, and lifted production exponentially. Nurturing the soil means it gives back to the animals and the end product.”

Changing to organic milk production has reignited Mark’s passion for farming and its “golden gift” has been retraining his thinking. It’s also been a special connection point with his grandmother, who has taken a keen interest in the process.

“She’s been really supportive of the organic road because that’s how they farmed. Everyone was organic 50 years ago. It’s about using what nature provides. I think organics can play a massive part in the turnaround for the environment that we all need to be part of.”

Image: Mark Spooner

The number of consumers in New Zealand is projected to reach 6.8 million by 2073 having passed 5 million in June 2020 (Stats NZ, 2020b; 2020c). This will continue to drive the demand on land to supply food, housing, and opportunities for recreation.

A growing population also partly drives urban expansion and the development of rural residential areas. Urban areas currently cover only 1 percent of land in New Zealand but 87 percent of the population live in towns and cities. (See indicator: Urban land cover.) About 80 percent of our population growth for 2018–43 is expected to be in the main urban centres (Stats NZ, 2017).

Most urban expansion is outwards onto productive land rather than upwards in multi-story buildings because it is cheaper to develop flat land than build on less productive hilly sites (MPI & MfE, 2019). Fields on the fringes of urban areas are therefore in demand for residential developments, which creates tension between the use of land for housing and for agriculture (Curran-Cournane et al., 2018; Greenhalgh et al., 2017).

Land use in New Zealand is strongly influenced by consumer demand here and overseas. Overseas markets are affected by global population growth and consumer preferences (Kelly, 2016; Spiess, 2016). The global population is projected to reach 10.9 billion by 2100 (UN DESA, Population Division, 2019). More people, higher incomes, and changes in behaviour can shift demand for certain goods – including food.

Overseas markets play a significant role in the relative profitability of different land uses. This is because half of our land is used for agriculture and forestry, with most of the products from these industries being exported. (See indicator: Exotic land cover.) In 2019, New Zealand’s land-based primary industries generated $44 billion in export revenue (MPI, 2020c).

Fluctuations in these factors can cause an increase or decrease in the area of land used to produce certain goods. As an example, higher milk prices caused a change in land use from sheep and beef to dairy farming – from 1983 to 1993, the area of land used for sheep farming decreased by 32 percent while land used for dairy increased by 22 percent (Willis, 2001). Increased milk prices helped make dairy farming more economically viable on land that was previously considered unsuitable. Higher prices were able to overcome the relatively high cost of the fertiliser and irrigation required (Wynyard, 2016). Higher milk prices also supported the intensification of dairy farming from the early 1980s, resulting in more milk produced per hectare through the use of fertiliser, irrigation, and cattle feed.

Māori freehold land (administered under Te Ture Whenua Act 1993) accounts for about 6 percent of New Zealand’s total land area (RBNZ, 2021). Its uses are diverse and a significant proportion supports land-based primary industries.

A significant proportion of assets in the primary sectors are in Māori ownership: 40 percent of forestry; 30 percent of lamb production; 30 percent in sheep and beef production; 10 percent in dairy production; and 10 percent in kiwifruit production in 2017 (Chapman-Tripp, 2017; MFAT, 2019).

Māori values, mātauranga Māori and tikanga can promote healthy soil, and the sustainable use of soil and food production (Hutchings et al., 2018).

Climate change is already affecting New Zealand through increased temperatures and changing rainfall (MfE & Stats NZ, 2020a). As the climate continues to change in the future, the changes it brings to the environment will affect the ways we use and manage land.

Land owners are already recognising climate change as one of the main influences on the ways they use, plan, and manage land resources (Driver et al., 2019) (see chapter 6: Land and a changing climate). Threats from rising sea levels are also likely to encourage moves away from coastal residential areas (MfE, 2020; Resource Management Review Panel, 2020). To accommodate people, it may be necessary to develop new housing in existing urban and residential areas and create denser cities. The need may be greatest in places like Wellington, where suitable land for additional housing is naturally limited, or where there is competition between highly productive land and housing.

Policies on trade, immigration, and housing can affect how, and how intensively, we use land. A range of policies direct the type and intensity of activities that can take place on different land in New Zealand. These include zoning and planning regulations that dictate how land in specific areas can be used. Local governments (regional, district, and city councils) put these policies into action by creating and enforcing regulations about land use and management.

Policies also influence markets and through them, land use. For example, national and international policies to address climate change, like the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme, can make plantation forestry a more or less attractive investment (Cortés-Acosta et al., 2020).

Internationally, environmental crises and competing uses for land have triggered the development of policies and conventions to guide land management and regulate land use. International agreements such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity influence options and decisions around land use (CBD, 2020; UNFCCC, 2021).

Policies that address environmental, social, and economic issues will continue to affect how land is used and managed. Innovative legislation and ways of governing natural resources have been introduced in this country. Tikanga, mātauranga Māori, and co-governance are being included more and more in legislation and policies that govern land use (see Ngāi Tūhoe and the co-governance of Te Urewera) (MPI, 2020a; Resource Management Review Panel, 2020).

Co-governance and co-management of land by indigenous people and government representatives is a unique way of managing natural resources. In a global first, Te Urewera (an area that was previously a national park) was given the same rights, powers, duties, and liabilities as a legal person.

The status of Te Urewera means that the land is not owned by anyone – this drives its use and management differently to land owned by the Crown, iwi, or individuals. Management of Te Urewera is based on tikanga and mātauranga, to preserve the mauri of the land and preserve it for future generations. This includes the obligations of kaitiakitanga. Decisions on what happens to the land are discussed by a board of representatives from Tūhoe and the Crown.

Te Urewera sets a precedent for recognising Māori rights and interests in our legal system. The recognition of natural features as legal persons may drive future Treaty settlements and co-management of land. The recognition could also provide a framework for natural resource management in other areas, both in New Zealand and internationally (Sanders, 2018).

This major legal shift is a direct reflection of the values underpinning te ao Māori (Māori world view) perspectives of the environment and opens up opportunities for wider understanding of the indivisible relationship between indigenous people, values, and landscapes. (Hutchings et al., 2018). It effectively gives the land itself a say in what it will be used for.

Read the long description for Healthy land, healthy soil, healthy people

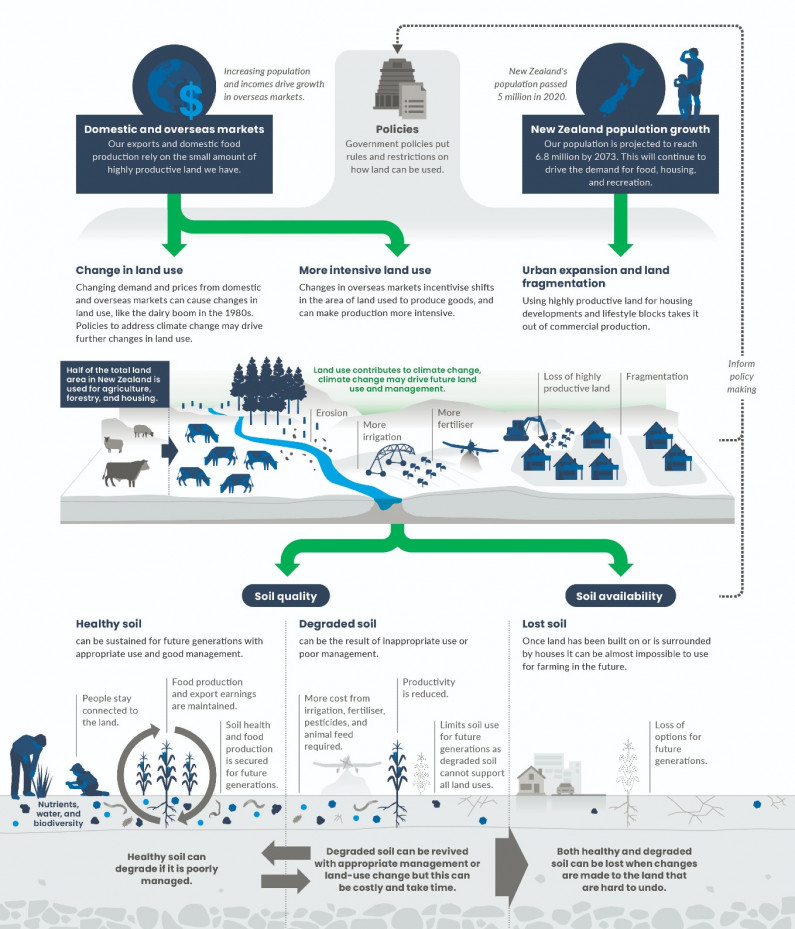

[An infographic connecting drivers of land-use change to the pressures, state, and impact on land and soil quality. The drivers (domestic and overseas markets and New Zealand population growth) flow into the pressures (change in land use, intensive land use, urban expansion, and land fragmentation) which flows into the state/impact of the soil in terms of soil quality and soil availability.]

Domestic and overseas markets

Increasing population and incomes drive growth in overseas markets. Our exports and domestic food production rely on the small amount of highly productive land we have.

Policies

Government policies put rules and restrictions on how land can be used.

New Zealand’s population growth

New Zealand’s population passed 5 million in 2020. Our population is projected to reach 6.8 million by 2073. This will continue to drive the demand for food, housing, and recreation.

Change in land use

Changing demand and prices from domestic and overseas markets can cause changes in land use, like the dairy boom in the 1980s. Policies to address climate change may drive further changes in land use.

More intensive land use

Changes in overseas markets incentivise shifts in the area of land used to produce goods, and can make production more intensive.

Urban expansion and land fragmentation

Using highly productive land for housing developments and lifestyle blocks takes it out of commercial production.

Half of the total land area in New Zealand is used for agriculture, forestry, and housing. Land use contributes to climate change, climate change may drive future land use and management.

Soil quality

Healthy soil can be sustained for future generations with appropriate use and good management. People stay connected to the land. Food production and export earnings are maintained. Soil health and food production is secured for future generations.

Degraded soil can be the result of inappropriate use of poor management. More cost from irrigation, fertiliser, pesticides, and animal feed required. Productivity is reduced. Limits soil use for future generations as degraded soil cannot support all land uses.

Lost soil. Once land has been built on or is surrounded by houses, it can be almost impossible to use for farming in the future. Loss of options for future generations.

Healthy soil can degrade if it is poorly managed. Degraded soil can be revived with appropriate management or land-use change but this can be costly and take time. Both healthy and degraded soil can be lost when changes are made to the land that are hard to undo.

Chapter 2: The driving forces

April 2021

© Ministry for the Environment