Waitī Freshwater

E tū Waitī e

He wai whakaata

He wai Māori

He wai oranga e

Behold Waitī

Reflecting water

Freshwater

Water that brings life

Waitī (Maia) is connected to freshwater: springs, streams, rivers, lakes, wetlands, and the plants and animals that live in freshwater. Waitī is comprised of two words wai (water) and tī which means sweet. Waitī is linked to Parawhenuamea, atua of freshwater and Rakahore, the personification of the rocks.

This section focuses on our essential connection to freshwater, and how we are impacted by the degraded state of many of our freshwater environments.

The mauri concept for Waitī links the health of freshwater to everything that is connected to it. If the mauri of Waitī is low, the mauri of everything that lives with her is negatively impacted (see the Matariki section for the definition of mauri used in this report). If she is healthy and well (mauri ora) we will see an abundance of food supplies such as whitebait (īnanga), eels (tuna), and freshwater crayfish (kōura).

The mauri of Waitī is affected by how we, as humans, have altered the freshwater environment. A healthy mauri means that eels and fish are free to swim in unpolluted water upstream to live or spawn without the damaging effects of dams, weirs, and other barriers. We would also have water clean enough to drink and swim in.

For Māori, the human and non-human worlds are indivisible; there are kinship relationships and therefore responsibilities towards natural features, including freshwater. A healthy mauri is a sign that a river is expressing its mana, or spiritual power. Indigenous frameworks are a part of our approach to freshwater management. They provide a hierarchy of needs greater than human needs, first and foremost giving back to the water, a preservation of mauri. This is followed by the health needs of the people (eg drinking water), and then the ability of people and communities to provide for their social, economic, and cultural wellbeing (MfE & MPI, 2020).

In addition to this, some settlements now require recognition of interconnectedness between the mana of wai and the mana of the iwi. These include Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River) which established in law Tupua te Kawa, the intrinsic values of the river, and Ngā Toka Tupua o Te Waiū o te Ika, which did the same for the Whangaehu River. These settlements enshrine in legislation the relationship between these iwi and their awa (river) (Nancy Tuaine, pers. comm., 2022).

Our interaction with freshwater builds knowledge and, in turn, identity. According to Rangi Matamua, “where there are bodies of freshwater, people inhabit those areas. When people inhabit an area, knowledge is formed. So, identity is dependent on freshwater that is embedded in the land” (Rangi Matamua, pers. comm., 2021).

The natural beauty of our rivers, lakes, and estuaries is central to our national identity. Aotearoa is perceived as a healthy place to live and grow up, and a high value is placed on the ability to swim in our rivers and lakes (Roberts et al, 2015). For Māori, water is a treasure (taonga) that people share an intimate connection with. The flow of freshwater through the landscape connects people and places to each other and to other forms of life (Anderson et al, 2019).

One indicator of the health of the waters and the people, and the close links between them, is the ability to fish and harvest food. Mahinga kai refers to the traditional Māori practices of gathering food, across the realms of land (whenua) and marine and freshwater. A range of foods are gathered from freshwater environments, including eel (tuna), whitebait (īnanga), freshwater mussel (kākahi), freshwater crayfish (kōura), and watercress (wātakirihi) (Collier et al, 2017). Flax (harakeke) and bulrush (raupō), plants that grow near waterways or in wetlands, are also used for harvesting, carrying, and preparing food.

More than simply food gathering, the ability to collect these resources affects the mana of an iwi or hapū, as they contribute to their capacity for manaakitanga – offering food from their whenua and wai to invited guests, an important part of hospitality. The protection of taonga species important to mahinga kai is therefore also the protection and maintenance of Māori language (te reo Māori), tikanga (customs/protocols), and Māori knowledge (mātauranga Māori): the language, practices and knowledge that are associated with them. In this way the ability to harvest these species is an indicator of the health of both the waters and the people (Rainforth & Harmsworth, 2019).

The Tupuārangi section noted the importance of access to greenspace for our mental and physical wellbeing. There is a growing body of evidence that spending time in or near ‘blue space’, such as rivers, lakes, and the sea, has similar benefits. These wellbeing benefits are evident when we spend this time actively (eg swimming, running, or walking) or passively (eg simply sitting by blue space). Benefits include reduced fatigue and stress, improved immune system function, and increased fitness (Gascon et al, 2017; Pasanen et al, 2019; White et al, 2020).

Many New Zealanders engage in freshwater recreation. A survey of almost 4,000 New Zealanders found that over 50 percent of adults participate in swimming outdoors at least once a year. Approximately a third of people engage in fishing at least once a year, and around 20 percent of people participate in kayaking or rafting at least once a year (DOC, 2020c).

Blue spaces also provide the opportunity for social connection. This is amplified through activities that involve collaboration with others, such as stream restoration (Meurk et al, 2013). These activities offer other mechanisms for increased wellbeing, including fostering a sense of belonging through enhanced connection with place, and a sense of contributing meaningfully towards creating a better environment (Morris et al, 2015).

Freshwater is essential to agriculture and electricity generation. As outlined in the Pōhutukawa section, the amount of irrigated land almost doubled between 2002 and 2017, and then decreased by 1.6 percent from 2017 to 2019. Increased irrigation has enabled greater agricultural production but it does put pressure on other areas, changing river flows and altering the habitats of native species. It can also impact recreation and drinking water supply (MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). (See indicator: Irrigated land.)

When compared to total energy consumption, Aotearoa has one of the highest proportions of renewable energy consumption in the world. Hydroelectric power is the biggest single contributor to electricity supply for Aotearoa, accounting for between 55 and 60 percent of generation each year (MBIE, 2020a). The artificial lakes created by dams are also used extensively for recreation (PCE, 2012).

However, dams also significantly alter the character of a river and the surrounding landscape. The mauri of the river is adversely impacted by it not being able to flow unobstructed from the mountains to the sea, and the spiritual significance to iwi rests in the river as a whole. Changes to flows and sediment transport negatively impact native plants and animals (PCE, 2012; Young et al, 2004). Dams also block the migrations of native fish and eels. The New Zealand longfin eel, endemic to Aotearoa, is particularly affected due to its migrations far inland. Some retrofitting of dams with devices to allow fish migration is currently being undertaken (Williams et al, 2017). For more on the impacts of dams see Our freshwater 2020.

Access to unpolluted water for drinking and recreation is vital for our health. Good quality water for hydration is essential for human digestion, improves our moods, energy levels, and alertness, and enhances physical and mental performance (Benton et al, 2015). During 2018–19, approximately a quarter of New Zealanders on registered drinking water supplies did not have access to water that met all the requirements of the Drinking-water Standards for New Zealand. These standards set acceptable levels of bacteria (such as E. coli), protozoa (such as Cryptosporidium), and chemicals (EHINZ, 2020).

Contamination of water used for drinking or preparing food is linked to a range of negative health outcomes. Contamination can come in a variety of forms, including the presence of illness-causing bacteria such as Campylobacter and E. coli or unsafe levels of contaminants such as nitrates (a form of nitrogen) or heavy metals. For instance, blue baby syndrome, also known as infant methaemoglobinaemia, is caused by excessive nitrates in drinking water (WHO, 2016).

Wetlands (repo) are an integral part of environmental and cultural landscapes. Repo act like giant filters, with the ability to remove nutrients and sediment from water. As well as protecting from extreme events like floods or storms, repo, especially peatlands, store large amounts of carbon that could be released if drained or disturbed (Ausseil et al, 2015; The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, 2019).

The ability of wetlands and estuaries to trap sediment and filter out pollutants before they reach the ocean are among the many benefits of wetland protection and restoration (NIWA, 2007). See Waitā section for the impacts of pollutants and sediment on freshwater and marine ecosystems.

Repo cover less than one percent of the land area of Aotearoa, yet they provide a habitat for two thirds of our threatened freshwater and estuarine fish species and 13 percent of threatened plant species. Wetlands are also vital for the survival of many of our native bird species, including the Australasian bittern (matuku), brown teal, New Zealand fernbird (mātātā), marsh crake (koitareke), and white heron (kotuku), who rely entirely on remnant wetlands (Clarkson et al, 2013; DOC, nd-c). They are a crucial source of mahinga kai, as the breeding grounds for tuna, īnanga, and other culturally important fish species (Clarkson et al, 2013). Repo are also a source of plants for medicinal use (rongoā), plants for use in weaving (raranga), and construction materials for houses (whare) (Taura et al, 2017, see also Tupuārangi section).

More than simply a supplier of food and materials, repo are an important part of the cultural landscape. They are deeply embedded in cultural life, as reservoirs of mātauranga Māori and places of deep historical, economic, and spiritual significance (Taura et al, 2021). If repo continue to be lost, cultural indicators that have been founded on generations of mātauranga Māori, such as those relating to watercress (kōwhitiwhiti), the giant spike sedge (kuta), and harakeke, will also be lost, along with the ability to interact with these places.

Many of our lakes and rivers have unnaturally high levels of nutrients due to leaching and run-off from urban or agricultural sources. We used both measured and modelled data to assess the water quality of our rivers and lakes. Computer models were used to estimate water quality for the period 2016–20 for all lakes and river segments, including those that do not have monitoring sites. Models are based on measured data, as well as variables such as climate, geology, topography, hydrology, and land cover. These models estimated that of 3,813 lakes in Aotearoa, 46 percent rated poor or very poor in terms of nutrient enrichment (as measured by Trophic Level Index) between 2016 and 2020.

Modelled data for 2016–20 indicated risk of environmental impairment (based on comparison with reference conditions) from at least one form of phosphorus (total phosphorus, or dissolved reactive phosphorus) in 64 percent of the river length of Aotearoa, and 69 percent for at least one form of nitrogen (total nitrogen, nitratenitrite-nitrogen, or ammoniacal nitrogen).

Water quality varies according to how much the catchment has been modified. Freshwater river quality tends to be poorest near areas with a high proportion of human modification and is highest quality in areas that have had the least modification. Monitored sites with higher proportions of human modified land cover in the upstream catchment area had higher concentrations of all forms of nitrogen and phosphorus, compared to sites with lower proportions of human modified land cover for 2016–20.

Between 2001 and 2020, trends were improving for nitrate-nitrite-nitrogen at 38 percent of monitoring sites, and for ammoniacal nitrogen at 61 percent of monitoring sites. (In this and the following section, improving and worsening trends include both likely and very likely statistical trends. See relevant indicators for trend assessment detail.) For the same period, 67 percent of sites had improving trends for dissolved reactive phosphorus. Freshwater systems are complex and nutrients can move at different speeds through catchments, so it is difficult to understand the causes of these trends (McDowell et al, 2021; MfE & Stats NZ, 2020b). For lake water quality there was insufficient data to determine 20-year trends across the network of monitored lakes. (See indicators: Lake water quality, River water quality: phosphorus, River water quality: nitrogen.)

Water clarity is a measure of underwater visibility in rivers and streams, while turbidity is a measure of how cloudy the water is. Excess sediment introduced to waterways by human activities such as forest clearing and urban development contributes to lowered clarity and increased turbidity. Computer models for 2016–20 estimated risk of environmental impairment (based on comparison with reference conditions) for turbidity in 37 percent of the river length of Aotearoa, and 9 percent for visual clarity. For the period 2001 to 2020, clarity and turbidity trends were improving at over half of monitoring sites and worsening at approximately one third. (See indicator: River water quality: clarity and turbidity.)

Macroinvertebrates – small animals without backbones such as insects and worms that live in the water – are used as an overall measure of river health. Macroinvertebrates play a central role in stream and river ecosystems by feeding on algae, aquatic plants, dead leaves, and wood, or on each other. In turn, they are an important food source for fish and birds. A high macroinvertebrate community index (MCI) score indicates a high level of river health.

Of the river length of Aotearoa, computer models estimated 17 percent had MCI scores that may indicate severe organic pollution or nutrient enrichment between 2016 and 2020. Only seven percent had modelled MCI scores indicative of pristine conditions with almost no organic pollution or nutrient enrichment. MCI scores worsened across 56 percent of monitoring sites between 2001 and 2020. (See indicator: River water quality: macroinvertebrate community index.)

The quality of our groundwater is mixed but improving in many places. For nutrients, between 2009 and 2018 more groundwater monitoring sites had improving trends than worsening. However, for E. coli, half of groundwater monitoring sites showed a worsening trend with only 18 percent improving over this period. For further discussion of groundwater see Our freshwater 2020 and indicator: Groundwater quality.

Polluted waters degrade the connections we have with Waitī. Water quality is especially important for drinking water and for recreational activities involving full immersion (eg swimming) or where water droplets may be inhaled (eg kayaking). E. coli is used as an indicator for the presence of other pathogens associated with animal or human faeces, including Campylobacter.

For the period 2016–20, computer models estimated 22 percent of river length in Aotearoa had an average Campylobacter infection risk of more than seven percent (the highest risk). Concentrations tended to be higher at monitored sites with higher proportions of human modified land cover in the upstream catchment area. Between 2001 and 2020 the number of monitoring sites with improving trends in E. coli (declining concentrations) was approximately equal to the number of sites with worsening trends (increasing concentrations). (See indicator: River water quality: Escherichia coli.)

Popular swimming spots in Aotearoa are monitored over the summer months for the presence of E. coli and the likelihood of cyanobacterial toxins. Toxic algae or cyanobacteria are also monitored at recreational sites as contact can be harmful to the health of both people and dogs. Toxic algal blooms generally occur as a result of high levels of nutrients (nitrogen and/or phosphorus) in warm, calm weather, forming thick mats on rocks or the riverbed. If water containing toxic algae is ingested, it can cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea, and can be fatal to dogs. Skin contact can cause rashes and irritation of the eyes, nose, and mouth (Canterbury District Health Board, 2020).

Properly assessing the health of freshwater requires a holistic view. Ki uta ki tai (from the mountains to the sea) is an approach to freshwater management based on Māori knowledge and practice. This approach recognises that the health and mauri of a river cannot be determined by looking just at the water. The whole catchment that is drained by a river must be examined, as an intact mauri depends on the status of all the interrelated components in the catchment. In this approach, the mauri of the water diminishes as it comes into contact with detrimental aspects of human activities (Tipa, 2009).

Ki uta ki tai methodologies to assess the overall health of a catchment are increasingly being used in freshwater management (Rainforth & Harmsworth, 2019). The mauri of the waterways is connected to the mauri of the people who live there, and the conditions of the water impact cultural wellbeing (Anderson et al, 2019). This means that ki uta ki tai approaches are intrinsically connected to particular places and the values of the people who live there. These values are not transferrable so it is not possible to understand the state of freshwater without also understanding the core values of the people in that place (Crow et al, 2018). The cultural health index is a national tool used to assess the health and mauri of a waterway and to monitor changes to it over time. It assesses a site’s accessibility, its ability to undertake mahinga kai activities, and cultural stream health. Cultural health index scores for waterways were very good or good at 11 sites, moderate at 21 sites, and poor or very poor at 9 sites, of 41 sites tested between 2005 and 2016. (See indicator: Cultural health index for freshwater bodies.)

While the focus in this section is the quality of our freshwater, there are knowledge gaps around how much freshwater is removed from rivers and aquifers for human use. We know how much freshwater extraction regional councils have given consents for. These data show a legal maximum, but we do not know how much water is actually being used. See Our freshwater 2020 for further discussion on water extraction.

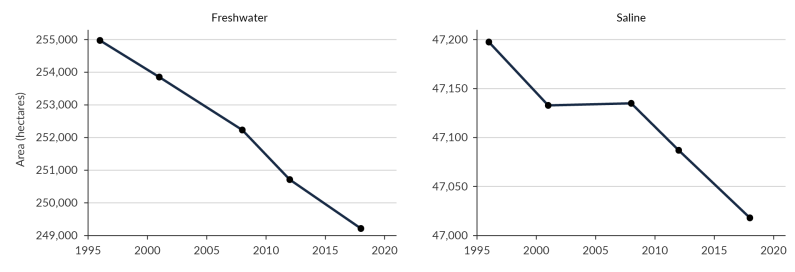

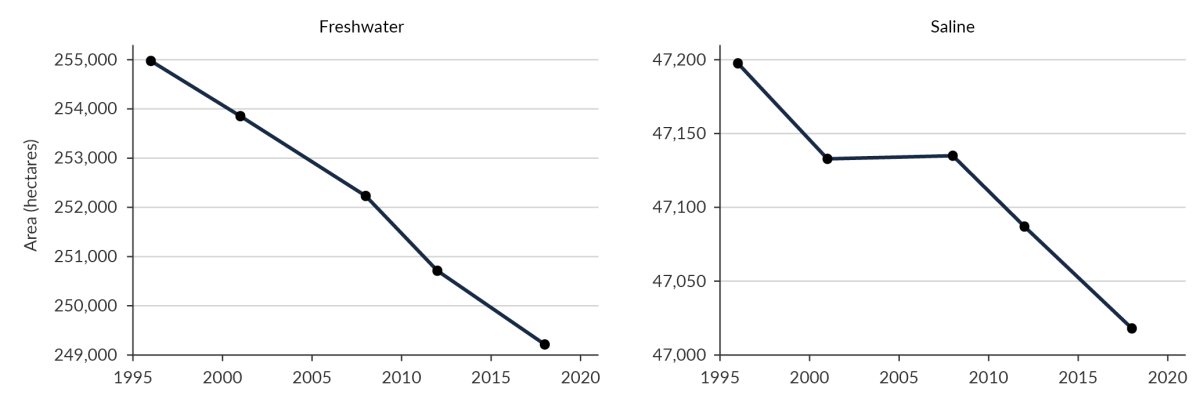

As outlined in the Pōhutukawa section, we have lost the majority of our historical wetland area (Dymond et al, 2021). The wetlands that remain still provide enormous benefits, but wetland loss is continuing, with freshwater wetland area decreasing by 1,498 hectares (0.6 percent) between 2012 and 2018, and saline wetland area decreasing by 69 hectares (0.1 percent) in the same period. (See figure 5 and indicator: Wetland area.)

In Southland, between 1996 and 2018, there was a net loss of 2,665 hectares of freshwater wetlands. Of the area of freshwater wetlands that were lost, 98 percent were because of conversion to land covers associated with farming and forestry. (See indicator: Wetland area.)

If wetlands continue to be lost, cultural indicators that have been founded on generations of mātauranga Māori will also be lost, along with the ability to interact with these places. The legacy of the drainage of organic soil wetlands is also having an effect, with a potential contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, in the order of 0.5 and 2 Mt CO2 equivalent per year (Ausseil et al, 2015).

Image: Data source — Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

Image: Data source — Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

The enormous importance of wetlands across so many domains means their protection and restoration has many benefits, to ecosystems and to people. Being involved in the active restoration of wetlands can enhance our wellbeing in many ways – from the individuallevel physical and psychological benefits of engaging in blue and greenspaces, to building and maintaining cultural knowledge of environmental indicators, through to the large-scale societal and environmental benefits that wetlands provide. There are many examples of wetland restoration projects across Aotearoa.

An agreement has been reached to construct a nationally significant wetland next to Lake Horowhenua. The project is a collaboration between Muaūpoko, Lake Horowhenua Trust (representing the owners of the lake), Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga, Horizons Regional Council, Horowhenua District Council, dairy farmers, horticulturalists, and the wider Lake Horowhenua community. Currently a dairy farm, the land will be converted back to a wetland which is intended to improve the water quality of the lake and restore its ecosystem (New Zealand Government, 2021).

Human activities are degrading our rivers, lakes, and groundwater with many lake and river sites scoring poorly in terms of water quality. Pollutants in our waterways and habitat destruction put pressure on our native freshwater ecosystems and fish species.

If we are unable to swim, kayak, or fish in our rivers and lakes, this undermines the physical and psychological benefits of blue spaces. Unhealthy freshwater ecosystems prevent us from gathering mahinga kai. This lack of access to freshwater spaces undercuts important aspects of how we identify as New Zealanders.

Waitī is connected to freshwater as well as the plants and animals that live in the springs, streams, river, lakes, and wetlands. She sits above her sibling Waitā, who is connected to the marine domain, reflecting the interconnectedness of water (wai) between these domains.

Our connections to freshwater are important to our identity. However, the state of our rivers, lakes, and groundwater is degraded in areas where land has been transformed by human activities.

Benefits from healthy freshwater:

Pressures on our freshwater ecosystems:

The state of freshwater affects our wellbeing through the health impacts of interacting with polluted waters.

Waitī is connected to freshwater as well as the plants and animals that live in the springs, streams, river, lakes, and wetlands. She sits above her sibling Waitā, who is connected to the marine domain, reflecting the interconnectedness of water (wai) between these domains.

Our connections to freshwater are important to our identity. However, the state of our rivers, lakes, and groundwater is degraded in areas where land has been transformed by human activities.

Benefits from healthy freshwater:

Pressures on our freshwater ecosystems:

The state of freshwater affects our wellbeing through the health impacts of interacting with polluted waters.

Waitī Freshwater

April 2022

© Ministry for the Environment