Tupuārangi Everything that grows above the earth

E tū Tupuārangi e

Ka pōkai tara ki runga

Whatitiri ngā parirau manu

Nau mai te pua nui a Tāne

Behold Tupuārangi

A great flock of birds above

With many wings like thunder

Welcome the bounty of Tāne

Tupuārangi (Atlas) is the star linked to food and growth above the ground. Tupuārangi also has a strong connection with birds. Tupuārangi is comprised of two words: tupu which can mean ‘new shoot’ or ‘to grow’, and rangi (sky), an abbreviation of ‘Ranginui’ (sky father). Tupuārangi has influence over the domains of Tāne, the atua of the forest, Haumietiketike, the atua of uncultivated foods and insects, and Tūtewehiwehi, the father of reptiles, fern roots, nīkau, harakeke, and silver tree fern (ponga).

This section focuses on land-based ecosystems, in particular our forests. It looks closely at some key species which illustrate our connection to Tupuārangi, including kererū, flax (harakeke), and mānuka.

Mātauranga Māori tells us that shifts in the mauri of any part of an ecosystem eventually affect the whole system (see the Matariki section for the definition of mauri used in this report). The use or harvest of parts of the ecosystem such as birds and plants may cause such shifts in mauri. Any damage or contamination to the environment will therefore also cause loss of, or damage to, mauri (Harmsworth & Awatere, 2013).

Some believe that if the stars Tupuānuku and Tupuārangi shine brightly when Matariki rises in the new year, people can plan for a plentiful harvest of crops, as well as berries, fruits, and birds from the forest (Matamua, 2017). Reflecting the connection of Tupuārangi to birds, during the rising of Matariki, kererū (Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae) were harvested in large numbers and preserved for the months ahead. This is seen in the proverb ‘Ka kitea a Matariki, kua maoka te hinu’ (‘When Matariki is seen the fat of the kererū is rendered so the birds can be preserved’) (Matamua, 2017).

The connections some Māori have with Tupuārangi can be demonstrated with the kererū. Historically, Tūhoe Tuawhenua (an iwi located in the Ruatāhuna region in Te Urewera) harvested kererū only in a particular season as a food source and for special occasions. There were strict observances around who would harvest kererū, as well as the ways in which their meat and feathers would be used and prepared (Timoti et al, 2017).

More recently, Tūhoe Tuawhenua have also reflected on the loss of kererū from the Te Urewera Ranges, particularly after the 1950s. Given the close linkages between kererū and Tūhoe Tuawhenua, some iwi members believe their declining interactions with kererū have contributed to the decline of the birds’ population (Lyver et al, 2008).

This loss of connection to Tupuārangi shows how the loss of access to ecosystems can diminish the sense of connection to place, identity (especially through whakapapa/geneology), and mana (power, authority). It also leads to the loss of Māori knowledge (mātauranga Māori) which comes from engaging with the environment (Lyver et al, 2008).

Practices concerning the harvesting of tītī (sooty shearwater or muttonbird) in the islands around Stewart Island (Rakiura) provide a further example of the inherent connections of humans to ecosystems – and the physical and spiritual worlds – in Māori worldviews. Tītī are an important source of food. Chicks are harvested by Rakiura Māori, who hold the manawhenua (territorial rights) on local breeding sites (King et al, 2013).

For Rakiura Māori, the harvesting of tītī (or ‘muttonbirding’) has not only food purposes but also significant social and cultural importance: in particular kinship links, the importance of keeping access rights to resources, and maintaining cultural knowledge (Wanhalla, 2009). Similar practices happen elsewhere in Aotearoa – for example, on islands off the Coromandel Peninsula iwi harvest small numbers of grey-faced petrel chicks (King et al, 2013).

Maintaining and rebuilding connections to customary harvesting of food (kai) reconnects people with land (whenua), wetlands (repo), and other ecosystems. Further, this supports the transmission of knowledge to the generations to come (Herse et al, 2021; Waitangi Tribunal, 2011).

Tupuārangi is also connected with plants and trees. Growing in our repo, harakeke has always been and continues to be an important resource in the Māori culture and economy. As well as being used for a wide range of medicinal applications, its leaves can be woven into baskets and other containers, mats, and clothing. The fibre (muka) can be twisted, plaited, and woven to make useful objects such as fishnets and traps, footwear, and ropes (DOC, 2022; Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, 2022).

Our forests and other wild places contribute to our wellbeing by giving us experiences, a sense of place, and enhancing our understanding of the environment. Sense of place is important when considering ecosystem values and environmental management (Dunball, 2020; Masterson et al, 2017). Recognising that people are part of ecosystems makes the management of ecosystems inseparable from their connections to human society (Ryfield et al, 2019).

Forests provide important economic benefits which support people’s livelihoods and wellbeing. Timber from pine plantation forests is one of our major export revenue earners. For the year ending December 2020, almost all (99.97 percent) of the logs harvested in Aotearoa came from plantation forests, with the remaining percentage harvested from indigenous forests. Of these, 87 percent of the trees in our plantation forests were Pinus radiata and 7 percent Douglas fir (Forest Owners Association, 2021). For the same year nearly 33 million logs were harvested, of which 61 percent were exported non-processed and the remainder processed in Aotearoa. The contribution of forestry and logging to GDP was 0.5 percent in 2020 (Stats NZ, 2021a). The total value of all forestry exports in 2020 was $5.5 billion (MPI, 2021f).

Honey is another important product we obtain from forest ecosystems. Twenty-seven thousand tonnes of honey were produced in Aotearoa in 2020 from 9,585 bee-keeping enterprises, most of them in the North Island. Honey export volumes have increased by 28 percent (2,223 tonnes) in 2020 compared to 2019 (MPI, 2021a). Mānuka honey in particular is an important export earner, with monofloral mānuka honey making up over half of honey export volume and commanding a higher price than other varieties for the year ended March 2021 (MPI, 2021e).

Geographic features and landscapes, such as forests and mountains, contribute to New Zealanders’ national identity (Blaschke, 2013; Chick & Laurence, 2016). When New Zealanders were asked what species and natural features they considered nationally iconic, species commonly mentioned were kiwi, ferns, kauri, pōhutukawa, tūī, kākāpō, kea, rimu, kōwhai, and tuatara (Premium Research, 2011).

Our forests and native ecosystems also provide opportunities for recreation, and to appreciate their wildlife and enjoy the scenic landscapes in which they occur. A survey of over 3,800 New Zealanders about their experiences in the outdoors found that 84 percent of respondents felt having access to the outdoor spaces of Aotearoa is a major advantage of living here (DOC, 2020b).

Access to greenspace enhances our wellbeing in numerous ways. We can receive many of these benefits through spending time in urban parks in our towns and cities as well as by visiting our more remote native forests. Natural features such as forests and parks in towns and cities provide many benefits for our health and lifestyle quality, including reduced air and noise pollution and increased biodiversity (Meurk et al, 2013).

These benefits are not always available close to where people live. For people living in towns and cities, accessing and benefiting from greenspace becomes more challenging (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021a). These benefits are unevenly distributed: lower-income communities in general have less access to greenspace and the wellbeing benefits it provides (Regional Public Health, 2010). The area of publicly accessible greenspace in Aotearoa urban areas is low compared to Europe (Souter-Brown, 2020), yet in 2019, 84 percent of New Zealanders lived in towns and cities (Stats NZ, 2021b). The highest percentage of greenspace in Aotearoa towns and cities is 13 percent in New Plymouth, while the highest in Europe is 68 percent in Oslo, Norway (World Cities Culture Forum, 2018). This lack of access to greenspace is likely to disadvantage urban Māori, who disproportionately live in lower socio-economic areas and tend to have fewer opportunities to connect with nature (Walker et al, 2019).

Access to nature and greenspace has a range of wellbeing benefits (MfE & Stats NZ, 2021a). It is positively associated with physical activity, and both physical activity and greenspace exposure are associated with greater emotional wellbeing (Markevych et al, 2017; Ward et al, 2016). In adults, greenspace is strongly associated with life satisfaction (Cleary et al, 2017; Houlden et al, 2018), while recreational visits to green and blue spaces improve mental wellbeing (White et al, 2021). Exposure to greenspace has also been shown to help build social connections (Markevych et al, 2017). People who live in areas with more urban greenspace perceive their neighbourhoods to be more socially cohesive (Holtan et al, 2015) and are more likely to volunteer (Ng et al, 2019).

There are mental health benefits for younger people in access to greenspace. In children, it is shown to reduce stress and improve attention, cognitive function, memory, and behaviour (McCormick, 2017; Sobko et al, 2018). In adolescents, exposure to greenspace is associated with reductions in stress, depressive symptoms, and psychological distress and improvements in mood, emotional wellbeing, and behaviour (Mavoa et al, 2019; Zhang et al, 2020).

Under COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, we learnt that access to nature was important for people’s wellbeing. During 2020 lockdowns in the UK, people reported better wellbeing and health if they had access to parks or gardens (Poortinga et al, 2021). In Aotearoa, people reported that connecting with nature during lockdown, such as listening to birdsong, brought a sense of calm and joy and eased anxieties (Greenaway, 2020).

This section examines the state of terrestrial biodiversity in Aotearoa, with a focus on the ecosystems and some of the plant and animal species that are especially important to Māori in the realm of Tupuārangi.

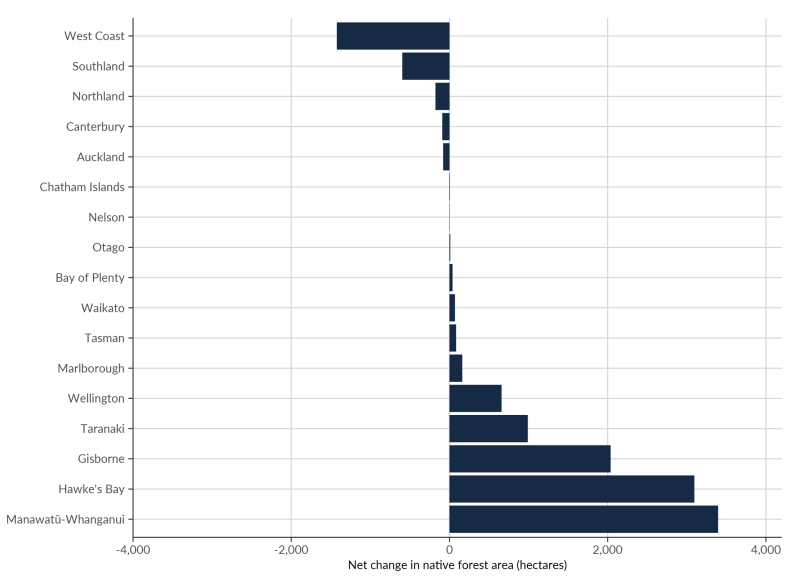

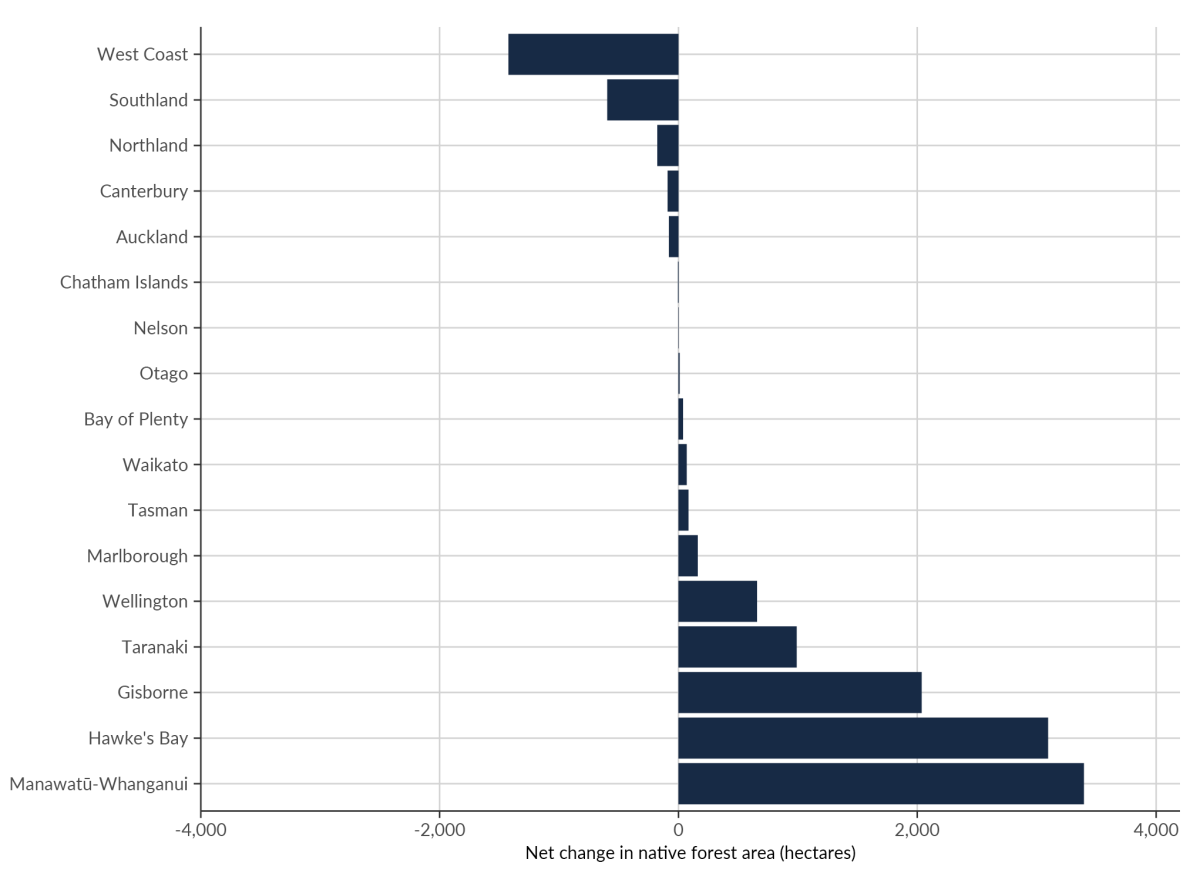

Native forests in Aotearoa have been steadily removed since human occupation, with less than one third of their original extent remaining (see Pōhutukawa section). Little of our lowland or coastal forests remain. In recent times, the area of native forest has remained fairly static. However, some regions have seen increases between 2012 and 2018 (in particular, Manawatū-Whanganui, Hawke’s Bay, and Gisborne). Other regions, most notably the West Coast, continued to lose indigenous forest (1,423 hectares lost in this region over this period). (See figure 4 and indicator: Indigenous land cover.)

In 2014, 71 ecosystems were identified as rare ecosystems in Aotearoa because they represented less than 0.5 percent of the country’s land area. Of these rare ecosystems, 45 were classified as threatened with collapse. Inland and alpine systems had the largest number of rare ecosystems (30), with just over half of these threatened (16). (See indicator: Rare ecosystems.)

Image: Data source — Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

Image: Data source — Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

As a consequence of topography and British planning tradition, cities such as Dunedin and Wellington have the benefit of an urban green belt (Meurk et al, 2013). Initiatives in other cities aim to increase the area of accessible greenspace. Urban forests enhance people’s wellbeing by providing recreation areas, community involvement and connection with biological heritage.

Waiwhakareke Natural Heritage Park in Hamilton is an example of successful urban forest restoration (Wallace & Clarkson, 2019). The Avon Ōtākaro River park proposed for Eastern Christchurch aims to restore native habitats for birds and other species, while also creating access for recreation and citizen science projects (Orchard et al, 2017).

Large scale conservation projects near cities seek to revitalise the environment through restoring the ecology and protecting native species. Examples include Cape to City in Hawke’s Bay (Predator Free Hawke’s Bay, nd) and Taranaki Mounga in Taranaki (Taranaki Mounga Project, 2022), which involve planting natives and predator trapping to increase habitats for birds.

With the reduction of our forests and wetlands, habitats for the plants and animals that depend on these ecosystems have vanished. Habitat destruction, along with the introduction of mammalian predators, has severely reduced the populations of many of our unique birds, reptiles, and plants (see Pōhutukawa section).

In 2016, 74 percent of our terrestrial birds (78 of 105) were threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened. For reptiles this proportion was far greater: 94 percent (116 of 124) were threatened or at risk in 2021, while for vascular plants it was 46 percent (1,253 of 2,744) in 2017. (See indicator: Extinction threat to indigenous land species.)

Looking at some of our treasured (taonga) species that were highlighted earlier in this section, kererū are classified as not threatened (population is stable) and have the qualifier ‘conservation dependent’. This means they are dependent on ongoing conservation efforts such as pest control (Robertson et al, 2017; Townsend et al, 2008). However, declines have been noted in some parts of the country, especially the South Island. Besides controlling predation by introduced mammals within forests, kererū recovery needs to also address the availability of food and forest areas for these birds (Carpenter et al, 2021).

Mātauranga Māori indicators of kererū populations in Te Urewera suggest that kererū in the area are in decline. The cultural indicators Tūhoe Tuawhenua use as evidence of this decline include audible and visual cues (rustling and fumbling noises, size of flocks, and visits to toromiro trees). Traditionally, the ease of harvest was also an indicator of population trends. These indicators reflect the breadth of interactions and knowledge that is involved in the connection Tūhoe Tuawhenua have with kererū. The loss of mana by the iwi over the kererū and forest and the retraction of the mauri of the kererū by Tāne-mahuta are some of the mātauranga explanations for the decline. Biophysical explanations for the decline are predation, competition with introduced species, variability in food supply, and loss of habitat (Lyver et al, 2008).

Eight out of the nine species of tītī are classified ‘at risk’ (Robertson et al, 2017).

There are two recognised species of New Zealand flax: Phormium tenax (flax, harakeke), and Phormium cookianum (mountain flax, wharariki). These are both considered ‘not threatened’ (population is stable to increasing) (de Lange et al, 2017). Flax grows throughout Aotearoa, but it is likely that some special cultivars cultivated by Māori for weaving may have gone extinct (Harris & Woodcock‐Sharp, 2000). Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research holds national collections of remaining unique cultivars and distributes plants to weaving groups and marae throughout the country (Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, nd).

Mānuka is widespread throughout Aotearoa (DOC, nd-a), but between 2001 and 2018 the area has decreased and some variants are threatened (de Lange et al, 2017). (See indicator: Indigenous land cover.) The pathogen myrtle rust introduced in 2017 is posing an increasing risk on the mānuka honey industry and other species of the Myrtaceae family (Sutherland et al, 2020).

While native forest cover has remained fairly static in recent years, we still see losses in some regions. Habitat destruction, along with the introduction of mammalian predators, has severely reduced the populations of many of our unique birds, reptiles, and plants, with many remaining threatened with extinction or at risk of becoming threatened.

Even small changes to our environment can have important consequences for ecosystems and species, and hence our wellbeing. Forested landscapes and native species are a big part of our identity as New Zealanders. Simply spending time in greenspace enhances our wellbeing, and we receive many other cultural and economic benefits from our land ecosystems.

Tupuārangi Everything that grows above the earth

April 2022

© Ministry for the Environment