Our marine environment at a glance

Te moana, the coast and oceans of Aotearoa New Zealand, are central to our identity and intertwined with our history – we are a maritime nation. For Māori, te moana is a source of whakapapa.

Image: TS Images, Photo New Zealand

We have one of the largest areas of ocean in the world. Our marine landscapes and habitats are diverse, supporting complex ecosystems and many unique species.

Our oceans support us. The marine economy added $7 billion to our economy in 2017 and employed more than 30,000 people. Healthy marine ecosystems provide essential benefits like taking up carbon dioxide, removing pollutants and providing kaimoana. In te ao Māori (the Māori world and worldview) the mauri, or life force, of a healthy moana enhances the mauri of those who interact with it.

This report summarises four priority issues for the marine environment and these issues mirror those we are also grappling with on land.

An estimated 30 percent of Aotearoa New Zealand’s biodiversity is in the sea but many species are in trouble: very few marine species are assessed, but of these 22 percent of marine mammals, 90 percent of seabirds and 80 percent of shorebirds are threatened with, or at risk of, extinction. The number of identified, non-native species established here is rising and now totals 214. Many non-native species can spread rapidly and some affect native species and habitats.

Estuaries and living habitats, like seagrass meadows and kelp forests, provide marine life with the food and shelter they need to thrive. Many biogenic habitats are decreasing or under threat. A decline in the number of kuku (green-lipped mussel), from over 100 million in 2007 to less than 500,000 in 2016, was observed in Ōhiwa Harbour. Declining marine health makes our coasts and oceans less resilient to disturbances, including climate change.

Our activities on land, especially agriculture and forestry, and growing cities, increase the amount of sediment, nutrients, chemicals, and plastics that enter our coasts and oceans.

Inter-tidal sedimentation rates have generally increased and become highly variable since European settlement. In estuaries and harbours across the Waikato region, historical sediment accumulation rates were less than 0.5 millimetres per year. After European settlement, rates became unstable, reaching almost 200 times historical rates. Thick deposits of sediment can smother animals and degrade habitats.

Coastal water quality is variable but generally improving nationally although very site dependent. Some pollutants, like pharmaceuticals and cleaning products, end up in the marine environment and the impacts of this are not well understood. Plastic is found throughout the ocean including inside shellfish, fish, and birds. Seabirds and other animals that eat plastic can get sick or die. Citizen science data collected at 44 sites showed more than 60 percent of beach litter was plastic. Pollution affects our ability to harvest kaimoana, swim, and fish in our favourite local places.

Our activities on coasts and in oceans like fishing, aquaculture, shipping, and coastal development, provide value to our economy and support growth.

Since 2009, the total commercial catch has remained stable at less than 450,000 tonnes per year. In 2018, 84 percent of routinely assessed stocks were considered to be fished within safe limits, an improvement from 81 percent in 2009. Of the 16 percent that were considered overfished, 9 stocks were collapsed.

Fishing has long-term and wide-ranging effects on species and habitats. The accidental capture (bycatch) of seabirds and marine mammals is decreasing but remains a significant pressure on some populations. Seabird deaths in the 2016/17 fishing year were estimated at 4,186. Seabed trawling and dredging have decreased in the last 20 years. About 24 percent of the fishable area has been trawled since 1990. Shallow areas are trawled more extensively than deeper areas, with varying impacts depending on fishing intensity, gear type, and vulnerability of habitat.

As an island nation, 99.5 percent of our imports and exports move by sea, and shipping traffic and vessel size has increased. Boat traffic is associated with the spread of non-native species and pollution and requires further construction of wharves and coastal infrastructure.

Most of our activities in the marine environment tend to increase in intensity towards the coast and, on top of the pressure from coastal development, this results in coastal environments being most impacted. Coastal waters tend to hold the greatest diversity of species.

Global concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gas are increasing because of activities like burning fossil fuels for heat, transport, and electricity generation. This is causing unprecedented change in our oceans.

The rate of sea-level rise has increased: the average rate in the past 60 years (2.44 millimetres per year) was more than double the rate of the previous 60 years (1.22 millimetres per year). Recent data suggests an even faster rate of sea-level rise. Extreme wave events may be becoming more frequent. Roads, bridges, coastal communities, and habitats are at risk from flooding and sea-level rise.

Our seas are warming. Satellite data recorded an average increase of 0.2° Celsius per decade since 1981. Years with an average temperature above the long-term average are more frequent. An unprecedented marine heatwave occurred in the Tasman Sea and near the Chatham Islands from November 2017 to February 2018 during our hottest summer on record.

Warmer seas affect the growth of even the smallest things in the ocean like plankton which can impact the whole food web. Some temperature-related changes in individual species and fish communities have been observed and tohu (environmental indicators that identify trends in the natural world) have changed.

Long-term measurements off the Otago coast show an increase of 7.1 percent in ocean acidity in the past 20 years. Oceans will continue to become more acidic as more carbon dioxide is absorbed. Shellfish, including oysters, pāua and mussels, are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity and this poses a risk for the shellfish-farming industry.

The pressures associated with biodiversity loss, activities on land, our activities at sea, and climate change have many effects on coasts and oceans. These can interact and lead to cumulative effects. This is one of the most urgent problems we face in our oceans. Given the complexity of the marine environment and lack of long-term data, the nature of cumulative effects is difficult to predict.

This report looks at the individual and cumulative pressures on kuku (green-lipped mussel). This is illustrative only and helps to build a picture of what the messages in this report mean within the context of a single species. The ability to report on the impacts of changes in the marine environment on species and habitats is often limited by a lack of baseline data, understanding of tipping points, and connections between domains.

Working together across mātauranga Māori and other science disciplines is improving our holistic place-based knowledge that is crucial in understanding cumulative effects. For Māori the whenua and moana are inextricably linked and there is a complement or balance for everything on land in the oceans.

Read the long description for The complexity of our marine environment:

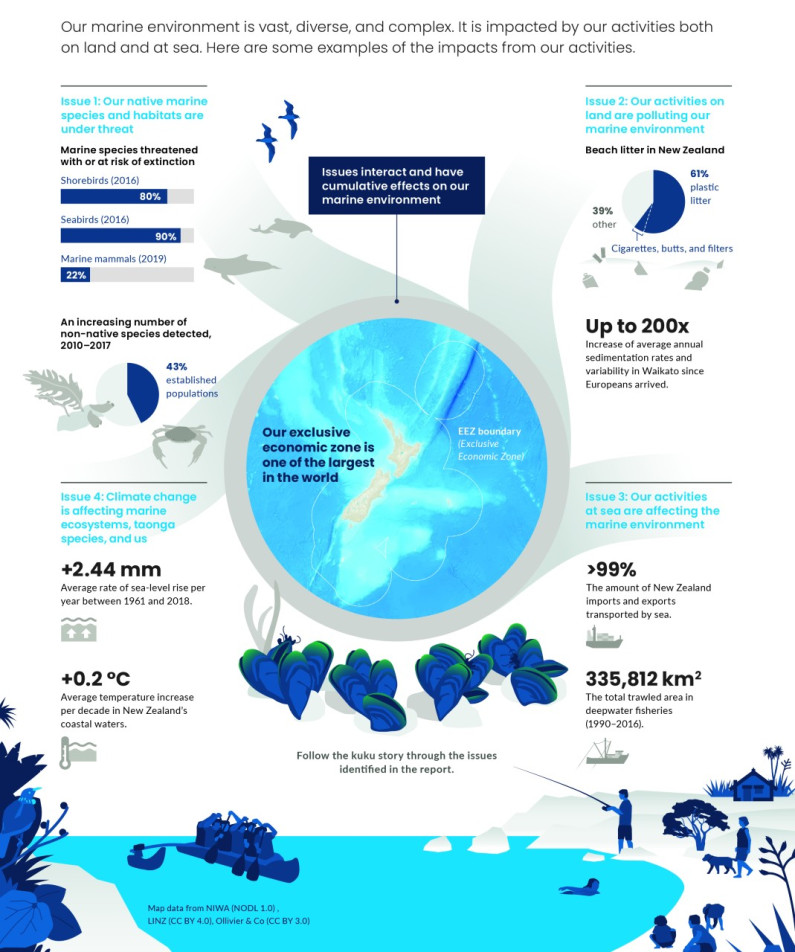

Our marine environment is vast, diverse, and complex. It is impacted by our activities both on land and at sea. Here are some examples of the impacts from our activities.

Our exclusive economic zone is one of the largest in the world.

Issues interact and have cumulative effects on our marine environment.

Issue 1: Our native marine species and habitats are under threat.

Marine species threatened with or at risk of extinction:

An increasing number of non-native species detected, 2010–2017

Issue 2: Our activities on land are polluting our marine environment

Beach litter in New Zealand

Up to 200x - Increase of average annual sedimentation rates and variability in Waikato since Europeans arrived.

Issue 3: Our activities at sea are affecting the marine environment

Issue 4: Climate change is affecting marine ecosystems, taonga species, and us

Follow the kuku story through the issues identified in the report

Map data from NIWA (NODL 1.0), LINZ (CC BY 4.0), Ollivier & Co (CC BY 3.0)

Our marine environment at a glance

October 2019

© Ministry for the Environment