The aim of this guide is to assist with the implementation of the National Environmental Standard (NES) for Sources of Human Drinking Water. The guide does not replace the NES regulations, but it is intended to make them easier for users to understand.

The aim of this guide is to assist with the implementation of the National Environmental Standard (NES) for Sources of Human Drinking Water. The guide does not replace the NES regulations, but it is intended to make them easier for users to understand.

In keeping with requests from stakeholders during the development of the NES, the wording of the regulation has been designed to provide councils with flexibility in the approaches they take to its implementation. Therefore, this guide should not be viewed as a prescriptive set of requirements to be followed to the letter. Instead, it is intended to provide plain-English guidance on the intent of the regulations and approaches to follow (or matters to consider) during implementation.

It is important to note that this guide is not a legal interpretation of the regulation and has no legal status.

The NES is a regulation made under sections 43 and 44 of the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). The NES was gazetted in December 2007. A six-month phase-in period provided councils, water suppliers and consent applicants time to become familiar with its requirements. The regulation came into force on 20 June 2008.

The purpose of the NES is to improve drinking water management by ensuring that catchments are included in the management of drinking water.

The NES has come about as a result of the Ministry for the Environment and the Ministry of Health working together to improve the management of drinking water in New Zealand. Although the quality of New Zealand drinking water is generally very good, disease-causing micro-organisms are present in many water sources. These enter water from a range of sources, including animal and human waste. This places drinking water supplies at risk. New Zealand has one of the highest rates of gastroenteritis in the developed world. While the reasons for this are not fully understood, drinking water is one of the routes by which people are exposed to the micro-organisms that cause disease.

Water quality monitoring involving the collection and analysis of water samples has historically been the main method for managing the quality of drinking water supplies. Relying solely on monitoring is, however, a poor defence against water-borne contaminants. Because of the time taken to analyse samples, results only provide historical water quality information unless monitoring is continuous. Thus consumers may have been receiving contaminated water for some time before a water supplier learns that the supply is contaminated.

Effective management of drinking water requires reducing the risk of contamination – from source through to the treatment plant and distribution system. If the risk of contamination is minimised at every step of the process, a failure at one step will not lead to catastrophic consequences. This is known as the ‘multiple barrier’ approach and is recommended by the World Health Organization.

The multiple barrier approach principle is internationally recognised as a cornerstone for managing risk in water supplies. The use of more than one barrier is encouraged in the Drinking-water Standards for New Zealand 2005 (DWSNZ). The presence of more than one barrier between water consumers and possible sources of pollution reduces the likelihood of contaminated water being supplied. If one barrier fails, there are others in place to protect consumers.

Key barriers include:

- protection of source water from contamination (eg, fencing rivers or streams so animals cannot get direct access to the water source. This reduces the type and concentration of contaminants that have to be dealt with by the water treatment plant)

- treatment plant processes:

- filtration improves water quality by removing particles

- disinfection (following particle removal) inactivates disease-causing micro-organisms (pathogens)

- protection of water after treatment to prevent re-contamination (eg, ensuring there is some chlorine in all pipes between the treatment plant and consumers, and regularly checking pipes to ensure there are no leaks).

- protection of water after treatment to prevent re-contamination (eg, ensuring there is some chlorine in all pipes between the treatment plant and consumers, and regularly checking pipes to ensure there are no leaks).

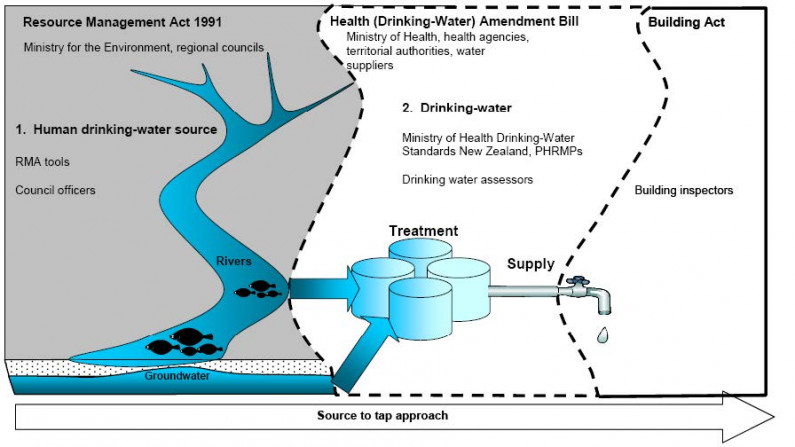

The NES for Sources of Human Drinking Water was introduced to strengthen the protection of source water. This is possibly the most important barrier because it reduces the contaminant load that later barriers have to remove. Figure 1 illustrates the multiple barrier approach to drinking water management.

Figure 1: Elements of the multiple barrier approach

Internationally, failure to recognise the importance of the multiple barrier approach has resulted in severe outbreaks of water-borne disease in developed countries, leading to serious illness and deaths. Analysis of numerous disease outbreaks linked to water supplies worldwide has revealed that contamination of water sources is often the cause.

Notable examples are outbreaks in Walkerton and Milwaukee in North America. In the small rural town of Walkerton, Canada, an outbreak of the toxin-producing bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157 in 2000 led to around 2000 cases of illness and seven deaths. Costs were estimated at CAN$155 million. The contamination that caused this event entered the water supply from effluent run-off. The other well-known case was water supply contamination by cattle feed lots in 1993. This led to an estimated 400,000 people becoming ill and over 100 dying in Milwaukee, in the United States.

New Zealand has been fortunate enough to avoid large-scale outbreaks of disease caused by contaminated drinking water, but a number of smaller outbreaks have occurred in the past 30 years. The largest of these was in Queenstown, where in 1984 an estimated 3500 people became ill as a result of drinking contaminated water. In July 2006 contamination of a drinking water source at Cardrona ski field resulted in over 120 cases of illness.

There have been many other outbreaks of water-borne disease in New Zealand. Further examples can be found in: A Ball. 2007. Estimation of Burden of Water-Borne Disease in New Zealand: Preliminary Report. Unpublished report prepared for ESR.

A study for the Ministry of Health estimated that the annual cost to New Zealand of water-borne disease was $25 million.

Before the enactment of the NES there was no explicit legislative requirement to consider the effects of activities on sources of human drinking water in regional or district plans. This gap left community water sources potentially vulnerable to contamination.

The power to control the effects of activities in catchments on drinking water sources rests with local government, under the RMA. Regional councils (including unitary authorities) have primary responsibility for managing water quality in the environment under section 30 of this Act.

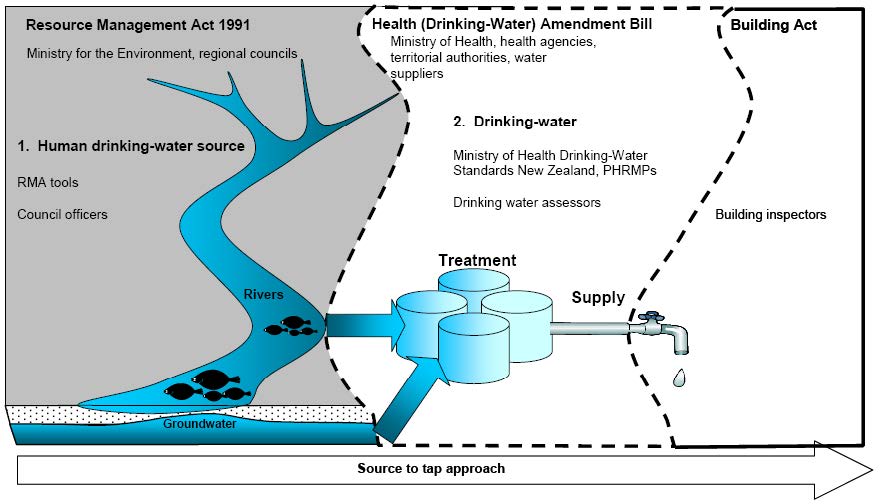

Health, local government, building and civil defence legislation applies to water only after it is taken from its source for treatment and/or delivery to the consumer. From the point of abstraction from source water, drinking water quality comes under the jurisdiction of health legislation, implemented by health agencies and local government (see Figure 2).

To achieve integrated management of water from source to tap, and therefore implement the multiple barrier approach, controls are needed under both the RMA and health legislation.

Before the NES, the degree of regulatory protection for drinking water sources in New Zealand varied greatly around the country. At the time the NES was developed only three of the country’s 16 regional councils comprehensively addressed protection of drinking water sources in their plans. The NES now requires regional councils to consider effects on drinking water sources when making decisions on resource consents and regional plans. Previously there was no clear mandate.

Figure 2: Key legislation and agencies involved in drinking water management

Notes:

- This figure shows only the key legislation associated with the management of drinking water. Other associated legislation includes the Local Government Act 2002 and the Civil Defence and Emergency Management Act 2002. The Local Government Act 2002 requires local authorities to undertake a specific assessment of the quality and adequacy of drinking water supplies (Part 7, section 126). However, there is no mandated requirement to manage source water quality. The shaded part of the diagram indicates the area of drinking water management where the NES applies.

- PHRMP = Public Health Risk Management Plans.

In September 2005, the Ministry for the Environment publicly notified the proposed NES for sources of human drinking water. Details of the original proposal were described in a discussion document, Proposed National Environmental Standard for Sources of Human Drinking Water, which was distributed during the submission period.

Four workshops on the proposed NES were held in Wellington, Dunedin, Christchurch and Hamilton in October 2005. Several separate meetings were also held with local government, drinking water assessors and other stakeholder groups. Also in 2005, the Ministry for the Environment’s Talk Environment roadshow travelled throughout New Zealand, holding over 30 meetings in 16 regions and talking to over 2700 people, and the proposed NES was one of the key topics discussed.

When the submission period closed on 28 November 2005 the proposal had been delivered to over 3100 people and 82 submissions had been received. An overview of these submissions is contained in the report Proposed National Environmental Standard for Sources of Human Drinking-water: Report on Submissions, available on the Ministry for the Environment website.

The NES was approved by Cabinet in November 2006 and gazetted in December 2007. It then had a six-month phase-in period before it officially came into effect on 20 June 2008.

See more on...

1. Introduction

May 2009

© Ministry for the Environment