Chapter 12 Building and construction

Download a PDF version of this chapter [PDF, 921 KB]

By 2050, Aotearoa New Zealand’s building-related emissions are near zero and buildings provide healthy places to work and live for present and future generations.

|

Projected emissions without the initiatives in this plan |

32.5 Mt CO2-e |

|

Projected average annual emissions without the initiatives in this plan |

8.1 Mt CO2-e |

|

Estimated emissions reduction from the initiatives in this plan |

0.9 to 1.7 Mt CO2-e |

In 2018, nearly 9.4 per cent of domestic emissions were building-related. These emissions are largely accounted for in the energy and industry, transport and waste sectors. For example, they include:

As we reduce our emissions and build Aotearoa New Zealand’s circular economy and bioeconomy, we can expect healthier homes, less reliance on global supply chains for construction materials and more sustainable living.

* Unlike other sectors, these figures reflect a ‘consumption’ approach that includes emissions accounted for in other sectors but for which building and construction is responsible (eg, emissions from energy used in buildings, emissions from the manufacture of building materials). Counting only emissions directly produced from buildings (predominantly fossil fuels used for space heating and cooling), building and construction produced 1.59 Mt CO2-e in 2018. This represents 3.6 per cent of total domestic emissions for that year (excluding biogenic methane).

Buildings are where New Zealanders spend most of their time living, working and playing. They impact on most wellbeing indicators at an individual, community and national level – they are our houses, our hospitals, residential and aged care facilities, our shops and offices, our warehouses and industrial buildings. Buildings are key to our everyday lives.

The building and construction sector is Aotearoa New Zealand’s fourth largest employer. It contributed NZ$20.5 billion (around 6.7 per cent) to Aotearoa New Zealand’s gross domestic product in the year ended March 2019.*

* See National accounts (industry production and investment): Year ended March 2019 [Statistics New Zealand website]

The building and construction sector was responsible for 7.4 Mt CO2-e of emissions in 2018. This represents 9.4 per cent of domestic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or over 15 per cent of emissions if biogenic methane is excluded (see figure 12.1).*

In addition, the building and construction sector was responsible for 2.9 Mt CO2-e of emissions that occurred outside Aotearoa, largely from the production of imported construction materials and products. These are not included in domestic emissions budgets for Aotearoa but are a significant proportion of the sector’s total emissions.

Emissions directly from buildings, such as fossil fuels used for space and water heating, are only one part of the emissions for which buildings are responsible. They also drive emissions that are accounted for in the energy, industry, waste and transport sectors.

To enable us to account for and reduce all of the emissions that buildings generate, this chapter uses a "consumption" approach (as recommended by He Pou a Rangi – Climate Change Commission) which incorporates all the emissions in Aotearoa related to buildings, regardless of the sector that produces them (see figure 12.1). This differs from the ‘production’ approach of other sector-specific chapters, which specifically incorporate emissions produced within that sector.

The consumption approach includes the impact of two types of building-related emissions.

* Figures in AR4 terms, based on the New Zealand's Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2018 published in 2020 as opposed to the most recent inventory published 2022.

Buildings and houses are long lived, and the amount of energy used to heat, cool, light and maintain them is affected by their original design and construction. Designing, building, using and deconstructing our buildings more efficiently will provide more opportunities to reduce emissions across many sectors.

Initiatives are underway across government and industry to reduce emissions from building and construction, and to meet the sector’s complex challenges – like workforce and skills shortages, material supply constraints, pipeline uncertainties, productivity constraints, and health and safety concerns.

More needs to be done to ensure this sector can meet the scale of the challenge. Everyone has a role to play – central and local government, business and industry, the finance and insurance sectors, and households and communities. The Construction Sector Accord provides a platform for much of this collaboration.

Together, government and industry must identify opportunities that reduce emissions, create cost savings and support affordability. For instance, changes to building designs or footprints can be cost neutral but significantly reduce emissions. Some opportunities have long-term cost savings, for instance, from reduced energy bills, but can have higher upfront costs.

To provide an equitable transition, the Government will work to understand potential costs and mitigate their negative impacts for groups, including workers, renters, seniors, disabled people and lower socio-economic groups.

The steps we are taking to reduce emissions have two objectives:

We can reduce the emissions created during the extraction, manufacture, operation and disposal of resources used in buildings through the actions below.

Actions in this focus area put in place requirements and support for people to measure or reduce their buildings’ embodied carbon.

The Government consulted on a Whole-of-Life Embodied Carbon Reduction Framework [Building Performance website] in 2020. The framework would require reporting and measurement of whole-of-life embodied carbon emissions – from manufacturing building materials to disposing of them at the end of a building’s life. The framework would cap new buildings’ whole-of-life embodied carbon and reduce the cap over time.

The Government is looking to use a climate innovation platform to enable the rapid development and adoption of innovative low-emissions building materials and approaches. This will involve policy and regulatory changes, international cooperation and supply agreements, and developing capability. These tools have the potential to lift competitiveness and increase access to innovation and affordability.

The Government supports innovative use of timber in buildings where this can reduce embodied carbon. The Wood Processing and Manufacturing Industry Transformation Plan and the newly established Timber Design Centre are two examples of work to develop a competitive and resilient timber industry (see chapter 14: Forestry).

To provide an equitable transition, the Government will look to support small businesses, Māori-owned businesses or emerging companies which may not have the same capacity as larger enterprises to access innovation opportunities or funding.

The Government will also explore providing independent specialist advice to households and supporting product information about low-emissions building products, which could also support households to take meaningful action.

* Environmental Product Declarations assess the greenhouse gas emissions from a product over the course of its lifecycle, in accordance with international standards.

Up to half of all waste in Aotearoa is made up of construction and demolition waste, with 20 per cent of this waste going to municipal landfill and 80 per cent to non-municipal landfills or cleanfills.* Adopting circular principles, where waste is minimised at the design, construction and deconstruction phases, will reduce emissions from landfills.

A more circular economy, where existing materials are reused and recycled, will lower costs and reduce emissions associated with extracting resources and manufacturing new materials (see chapter 15: Waste and chapter 9: Circular economy and bioeconomy).

The transport of building and construction materials, products and workers generates emissions. Improving coordination and project management across the construction supply chain will help reduce transport costs and emissions.

* Reducing building material waste [BRANZ website]

Reducing building-related emissions requires lower-emissions alternatives to be the norm for both the sector, and for households and building owners. These must be competitive to produce and affordable. Households and building owners, government and the sector must make informed, deliberate decisions about embodied carbon and operational efficiency when considering the design and use of buildings.

We must adopt and mainstream new manufacturing and construction processes, technologies, building designs, materials and products to reduce building-related emissions and increase affordability and competitiveness.

The Government owns, manages or procures a large number of buildings, including public and defence housing, schools, hospitals and office buildings. The Government can use its purchasing power to drive the market towards low-emissions alternatives.

Operational emissions can be reduced by improving building design so that maintaining a comfortable indoor environment uses less energy and by using energy from low-emissions sources. This can also reduce energy costs across a building’s lifetime.

Half of all Aotearoa New Zealand’s electricity is used in buildings, mostly for heating and cooling spaces and water heating. Building electricity use often occurs in peaks – many homes will use heating at the same time, such as on cold evenings. Peak electricity is more likely to be generated by burning coal or gas. Many buildings in Aotearoa are also hard to heat and not dry or healthy, which can contribute to poor health outcomes for building users.

The Government has already made significant investments to lift buildings’ energy efficiency, improve their quality and drive down energy costs. For example, more than 85,000 insulation and heating retrofits have been completed under the Warmer Kiwi Homes programme since July 2018. However, more needs to be done for both new and existing buildings to meet the scale of the emissions reduction challenge.

Further reducing operational emissions requires more substantial changes to the Building Code. In 2020, the Government consulted on the Transforming Operational Efficiency framework [Building Performance NZ website]. It proposes to cap buildings’ use of energy and water and defines quality measures for indoor environments. Implementing any proposals will require care to avoid unintended consequences.

This work also presents an opportunity to provide more broadly for an equitable transition. Complementary actions will be explored such as improving building accessibility and seismic resilience, supporting workforce development, and enabling medium- and higher-density housing options that support more liveable urban environments.

The building regulatory system largely focuses on the performance of new buildings. However, we also need to address existing buildings. This means reducing emissions by improving their performance and energy efficiency.

Supporting existing buildings to become low emissions is an important part of an equitable transition. People living in existing buildings, including vulnerable populations, are less likely to benefit from regulation that ensures new buildings are warmer, drier and healthier.

Actions currently in place – such as the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority’s Warmer Kiwi Homes programme, the continued rollout of the Healthy Homes Standards, and Kāinga Ora’s work to improve the operational efficiency of its building stock – will address some of these impacts (see the case study below).

Ngā Kāinga Anamata (homes of the future) is part of Kāinga Ora’s carbon-neutral programme. The proposed public housing development aims to meet the aspirations for mitigating carbon under the Building for Climate Change programme.

The project in the Auckland suburb of Glendowie plans to deliver 30 new homes in five, three-level apartment buildings. Each building will use common structural systems and materials, and achieve significantly reduced carbon and energy outputs compared to typical 2020 construction.

The project team conducted whole-building lifecycle carbon assessments throughout the design process. The result is a lifecycle carbon reduction of approximately 74 per cent less than typical 2020 apartment construction. This includes timber’s biogenic carbon sequestration, or a 58 per cent carbon reduction without.

If agreed for delivery, Ngā Kāinga Anamata will share lessons and insights to prove low lifecycle carbon construction is possible now. It will accelerate decarbonisation in new residential construction. Monitoring and evaluation during building and occupancy will establish the overall cost and benefits of low-carbon housing. The project will report this to the industry to help drive change towards a decarbonised, climate-resilient built environment.

Ngā Kāinga Anamata was showcased as one of only 17 global initiatives in the COP26 Build Better Now pavilion – part of the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

About 4 per cent of Aotearoa New Zealand’s domestic emissions in 2018 were from fossil fuels used in buildings for space and water heating, cooling and cooking.

Transitioning buildings from fossil fuels to low-emissions renewable energy will reduce these emissions. It will also improve the health and wellbeing of building users. To be equitable, the transition must take care to mitigate unequal impacts for building users, households, communities and industry.

For example, fossil fuels are currently the only viable energy option in some rural and off-grid communities, homes and marae. Measures that affect the affordability or supply of fossil gas or coal may disadvantage these people unless the transition is supported.

Fossil fuel use in buildings will be reduced through actions already covered in the emissions reduction plan, including:

Continuing to reduce building related emissions will require looking ahead and establishing relationships, training systems, data and regulatory systems to support change and make the most of low-emissions opportunities.

The Government and the building and construction sector must be well positioned to understand and respond to the diverse needs and aspirations of Māori. Partnership in the building and construction sector needs to be improved to support Māori aspirations and progress key opportunities across the sector.

Hapū, iwi and whānau Māori are significant land and property holders, business owners and participants in Aotearoa New Zealand’s construction sector. Empowering Māori and maximising opportunities will contribute to better outcomes, both for Māori and emissions reduction.

High-quality, user-friendly data and evidence is needed to introduce regulation change for operational emissions and embodied emissions reduction. Data and evidence also supports monitoring and evaluation and allows the sector and households to make informed decisions about the emissions impacts of their building choices.

New Zealanders could benefit significantly from low-emissions buildings, materials and practices that are not yet mainstream. Shifting attitudes and behaviours could result in emissions reductions becoming a core consideration when procuring or undertaking building work. This will support business competitiveness and raise the real (and perceived) affordability of low-emissions approaches.

Supporting people to become more aware of low-emissions building and construction opportunities will underpin much of the work in the building and construction sector in the first emissions budget period and complement initiatives across government.

Reducing emissions in the building and construction sector will create new economic and job opportunities across the sector – including for people and skills that the sector has not traditionally employed.

To take advantage of these opportunities, it is important that the workforce has the right skills, capabilities and capacity. As well as supporting an equitable transition, the actions preparing –and upskilling – the workforce could also help address existing shortages.

The Government will partner with the Construction Sector Accord’s people development and environment workstreams, Māori and Pacific businesses and workers, and across regions, industries and professions, to realise opportunities and an equitable transition.

The Government will future-proof the Building Act 2004 to ensure it is clear about the Government’s priorities for climate change. This will lay the foundation for future legislative and regulatory action that might be required to progress emissions reduction and adaptation work.

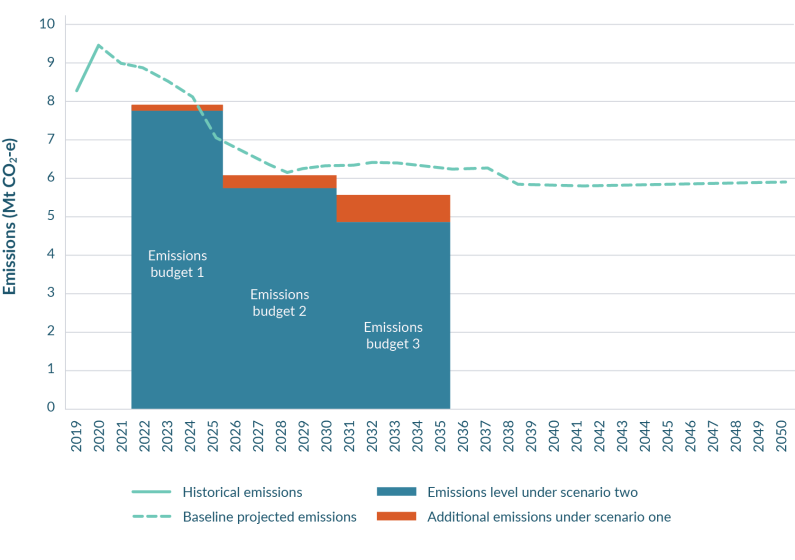

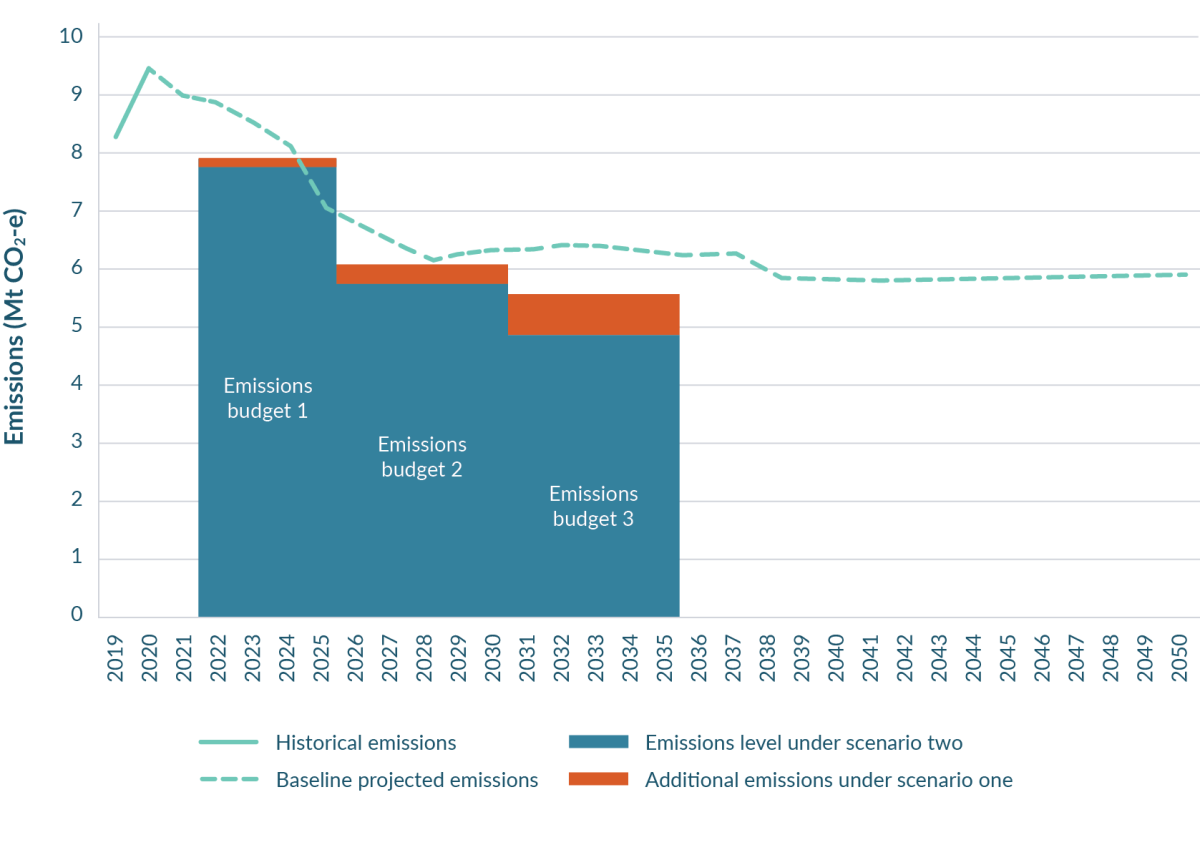

Building-related emissions are expected to reduce by 0.9 Mt CO2-e to 1.7 Mt CO2-e in the first emissions budget period, mainly through the potential impact of non-regulatory initiatives such as a behaviour change programme and providing technical infrastructure such as data and tools.

Regulatory actions that could come into force from 2025 are expected to have a more significant impact on emissions reductions in the second and third emissions budget periods. The specific reductions will depend on the strength and speed of the regulatory settings, which the Government will decide at the appropriate time. As an illustration, building-related emissions reductions of between 1.5 Mt CO2-e and 3.4 Mt CO2-e could be realised in the second emissions budget period, and between 3.9 Mt CO2-e and 7.5 Mt CO2-e in the third emissions budget period.

The Government has modelled two scenarios to show the sector’s potential emissions reductions from the actions above. The scenarios show the impact that different timelines and initiatives could have on emissions from the building and construction sector.

The modelled emissions reductions mostly occur in the energy and industry sectors, with some reductions in the waste and transport sectors.

The Government is putting in place the systems and settings to facilitate a low-emissions building and construction sector, but we all need to work together to meet our 2050 targets.

In their role as building-consent authorities, local government co-regulate the building system. They will have a role to play in implementing proposed Building Code requirements to report and measure whole-of-life embodied carbon and operational emissions. Local government will also have a role in reducing construction and demolition waste.

All parts of the building and construction sector have a role in reducing emissions. For instance, designers, engineers and architects can develop and offer lower-emissions building designs, builders can reduce construction waste onsite, and industry training organisations can build the climate change skills and capability needed for the workforce.

The financial and insurance sectors also have levers that may enable or incentivise households and businesses to opt for low-emissions houses and other buildings. For example, mortgage lenders and brokers can offer "green loans" (loans with more favourable terms for more climate-resilient buildings) or adapt lending criteria for efficient, low-emissions buildings with small footprints.

The 2020 National Climate Change Risk Assessment for New Zealand identified "risks to buildings due to extreme weather events, drought, increased fire weather and sea-level rise" as one of its 10 most significant climate change risks, based on urgency.*

The forthcoming national adaptation plan (to be released by August 2022) will outline regulatory and non-regulatory actions to address risks. These actions will be jointly developed by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and Te Tūāpapa Kura Kāinga (Ministry of Housing and Urban Development) to ensure they consider the linkages between the building regulatory system, housing and Māori priorities.

The Government will ensure system settings mitigate the risk of trade-offs between emissions reduction and building adaptation or resilience. In addition, the national adaptation plan will outline appropriate policies and support to ensure Māori can achieve both adaptation and emissions reduction goals. Work with Māori outlined in action 12.5.1 will support the development of further actions.

* For an assessment and more details of this risk, see the Ministry for the Environment National Climate Change Risk Assessment for Aotearoa New Zealand: Main report – Arotakenga Tūraru mō te Huringa Āhuarangi o Āotearoa: Pūrongo whakatōpū [PDF, 5.1 MB], at pp 82–87.

Chapter 12 Building and construction

May 2022

© Ministry for the Environment