How to develop climate scenarios

This page has the step by step process to develop your own climate scenario.

This page has the step by step process to develop your own climate scenario.

You can develop your own scenarios for testing a particular policy or strategy rather than using an existing set of scenarios.

Developing scenarios can be done by following the steps outlined on this page and by drawing on existing scenarios as a starting point.

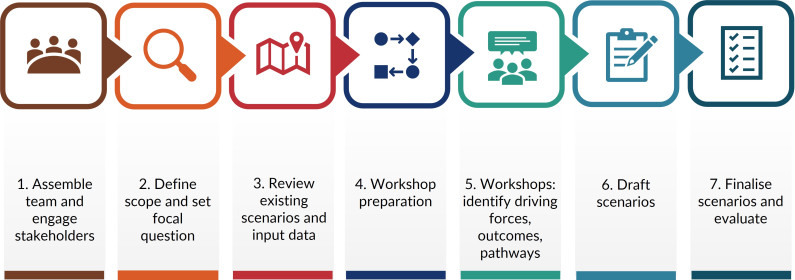

The image shows the scenario development process. It follows seven steps:

Step one: Assemble a team

Step two: Define the scope

Step three: Define scenario archetypes

Step four: Workshop preparation

Step five: Workshops

Step six: Draft final scenarios

Step seven: Finalise scenarios

The image shows the scenario development process. It follows seven steps:

Step one: Assemble a team

Step two: Define the scope

Step three: Define scenario archetypes

Step four: Workshop preparation

Step five: Workshops

Step six: Draft final scenarios

Step seven: Finalise scenarios

The output of this step is a scenario planning team responsible for co-design and delivery of activities.

The first step in scenario development is to assemble a team, determine roles and responsibilities and identify how the process will be used by the organisation.

Several different groups may be required.

Assemble a diverse team from across different functions and levels of the organisation to ensure that all relevant factors are considered.

Before starting the process, make sure your team has a good understanding of:

Climate change presents a complex challenge for Māori. The scenario development processes should give effect to rangatiratanga and mana whenua’s status as Treaty partners.

Organisations should establish a separate, dedicated scenario process or engage mana whenua early. Provide time and space for mana whenua who may be impacted, to define for themselves the problem, expectations, and anticipated outcomes of the process.

Policy makers should consider the Guidelines agreed by Cabinet for Treaty of Waitangi in policy development and implementation.

Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet Treaty of Waitangi analysis.

Bringing in a variety of perspectives will reduce the risk of ‘groupthink’ and defaulting to ‘business-as usual’ norms. To be useful, scenarios need to be challenging.

The output of this step is a statement on the scope of the scenario (or scenarios) and agreement on a focal question.

Once the team has been assembled, the next step is to clarify the question to be addressed. The scenario team can provide clarity, direction, and boundaries to help define or identify the problem or guiding question for the project.

Scenarios can be developed to assess a portfolio of issues across multiple sectors in a region, state, or nation or focus on a discrete project within one sector or within an organisation.

In practice, the broader the scope of the project, the more generic the scenarios will become and the less decision-useful they may be. With a narrower scope and clearly defined focal question, the scenarios will be more targeted and therefore more likely to usefully inform decisions and operational planning.

You may find visual approaches helpful at this stage, such as mind maps, to collaboratively define your project boundaries.

The scope should clearly define the project focus and boundaries, such as:

Once the scope is clear, a more discrete focal question can be defined. The focal question should be:

For the public sector, applying climate scenarios can take many different forms. An important part of defining the scope of your scenarios is deciding how they will be used in practice. The scenarios should be designed with this end use in mind.

Read how to apply climate scenarios

When selecting a time horizon for your scenarios, factors to consider include:

Challenge norms when you select time horizons, as climate-related risks, opportunities and impacts may keep evolving beyond the timescales of typical planning processes.

In most scenario archetypes, physical risks are relatively minor before 2050.

Therefore, using longer time-horizons (eg, 2070 or 2100) may be necessary to avoid missing some key risks.

Using longer time horizons helps to capture potential climate impacts that most current global scenarios place farther into the future, but which might happen faster in reality (as has been consistently experienced over the past decade).

Time horizons from existing scenarios, such as New Zealand sector scenarios, can be a useful starting point. You should consider, however, whether adjustments to these time horizons are needed to improve relevance to your organisation’s situation and your chosen focal question.

The output of this step is relevant, plausible, and scientifically and technically robust scenario archetypes and supporting data.

Once the focal question and scope has been set, the next step is to decide how many scenarios you need.

We strongly recommend developing and applying at least three scenarios. Three scenarios will better enable you to test a range of plausible, uncertain futures.

Each of your scenarios should have an ‘archetype.’ Scenario archetypes have similar underlying assumptions, and trends that facilitate comparisons.

Your scenario archetypes should include:

There are multiple ways to go about defining your scenario archetypes.

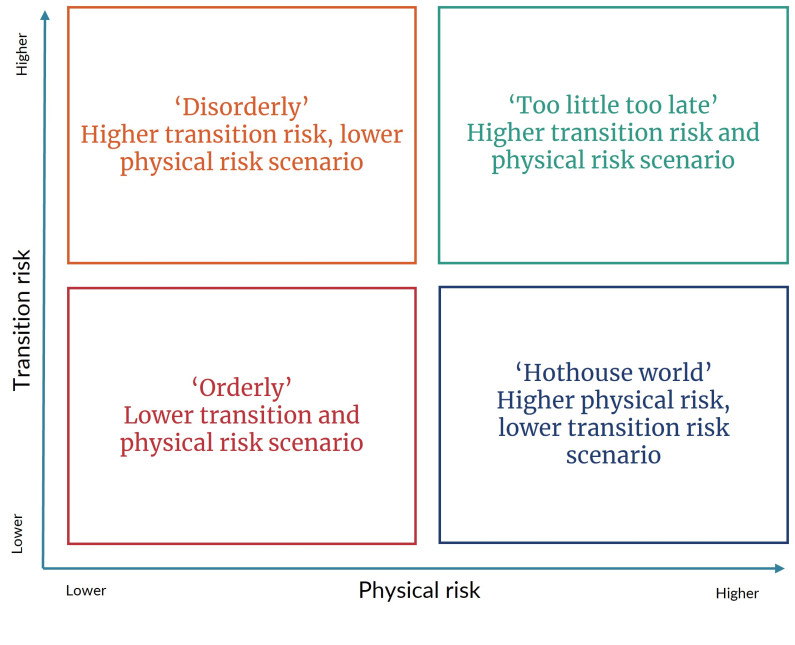

The four quadrants developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) is one popular framework for selecting climate scenario archetypes.

These four quadrants are designed so that the scenarios test differing extremes of physical and transition risks. Depending on how many scenarios you decide to develop, you may base your scenarios on two, three, or all four of the quadrants.

NGFS scenario archetypes:

NGFS scenario archetypes:

The four quadrants developed by the NGFS are not the only framework that can be used to define scenario archetypes.

Depending on your focal question, you could consider scenario archetypes that explore other axes, such as:

Regardless of how you define your archetypes, to further develop them you will want to draw on elements of existing scenarios. Depending on what is most relevant to your focal question, you may decide to draw on elements of many existing scenarios, or just a few.

Drawing on existing scenarios to develop your scenario architecture is as much of an art as it is a science. Existing scenarios were all designed by different entities for different purposes.

It is essential to check that existing scenarios are broadly consistent when combining them to create your scenario archetypes. Organisations can also change assumptions in existing scenarios in a transparent way if they consider it necessary.

You may decide to draw on elements from:

Explore the catalogue of climate scenarios

Read more about scenario archetypes and how to use existing scenarios in a consistent way on page 50 of Staff Guidance: Entity Scenario Development [External Reporting Board website].

The output of this step is materials needed for workshops, including presentations, templates, and agendas.

Once the scenario archetypes have been defined, the next steps are to prepare for and facilitate workshops to refine them into draft scenario narratives.

The workshop preparatory phase involves assembling materials for the scenarios workshops (see step five).

Draft materials – including process design, and archetypes – can be tested in advance with the smaller, support group. If done well, these people will provide critical feedback that you can discuss and where required, take on board. This smaller support group will also become your ‘workshop champions’.

Example workshop materials could include:

The output of this step is to undertake workshops (online or face-to-face) to go through the process of identifying and ranking driving forces, assessing these against archetypes and developing draft scenario narratives.

Workshops can be held in person, online, or in hybrid format, and should be a minimum of two-three hours each or ideally half a day.

The diagram shows from left to right:

The diagram shows from left to right:

The first workshop’s aim is to develop a shared baseline understanding of the ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how’ of scenarios. It’s a chance to introduce key terms and walk the group through the main points of the process, explaining the logic of each step.

This workshop focuses on identifying the underlying forces that could shape the organisation’s future in relation to the focal question.

Driving forces are the forces of change outside the organisation that will shape the dynamics of possible futures in both predictable and unpredictable ways. Things to consider include key trends and factors and drivers of change. Thinking from the “outside in” – starting with broad societal and environmental factors – can help spur identification of external driving forces.

You may wish to use a common framework for identifying driving forces, such as the STEEP framework (social, technological, economic, environmental, and political).

| Category | Description | Examples in New Zealand context |

|---|---|---|

| Social | Demographics, social norms, lifestyle trends, health, education, rural-urban divide | Migration, attitudes to lifestyle and consumption, distribution of wealth and opportunity, attitudes to science and the role of business in society |

| Technological | Research trends, emerging and/or disruptive technologies, technology uptake and market penetration | Biological methane inhibiting technologies, battery storage and electricity distribution, development of alternative or synthetic proteins, digitalisation |

| Economic | Macro and microeconomic policy, trade settings, finance, capital allocation | Interest rates and capital costs, public and private sector debt, trade settings and deals, value of exports |

| Environmental | Climate change, biodiversity loss, water, pollution, land use change, waste management, energy | Physical climate impacts, freshwater regulation and land use regulations, waste disposal options, energy systems |

| Political | Climate policy, law, regulation, legal liabilities, political attitudes and trends | Te Tiriti, net-zero emissions targets, emissions regulations, border settings and freedom of movement, legal challenges |

In addition to a common framework, such as STEEP, you should also consider cultural driving forces.

| Category | Description | Examples in New Zealand context |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Cultural practices and infrastructure | Mātauranga Māori, physical climate impacts on wāhi tapu, mahinga kai, urupā, and marae |

Explore the catalogue of climate scenarios

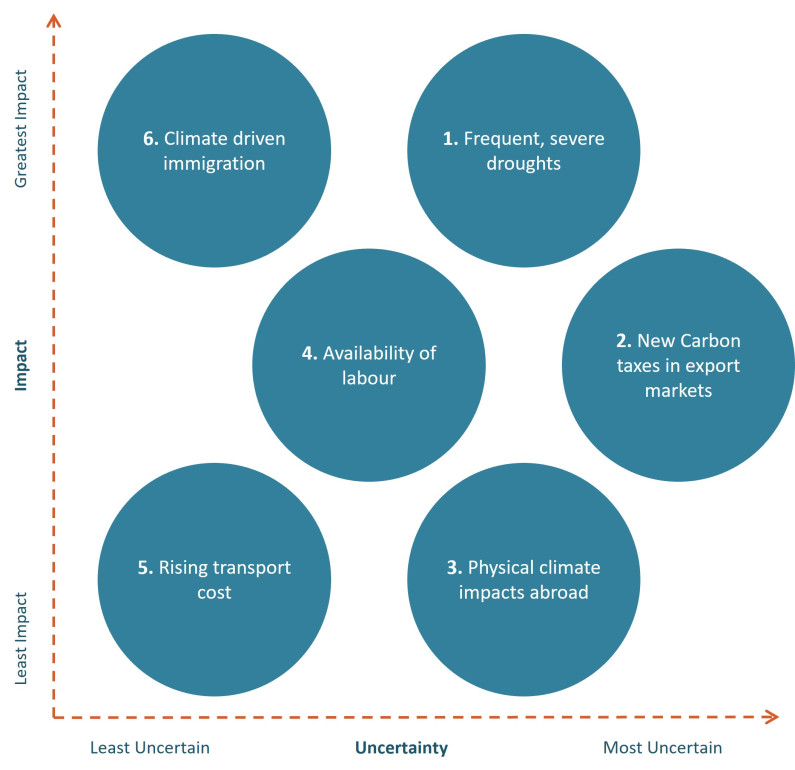

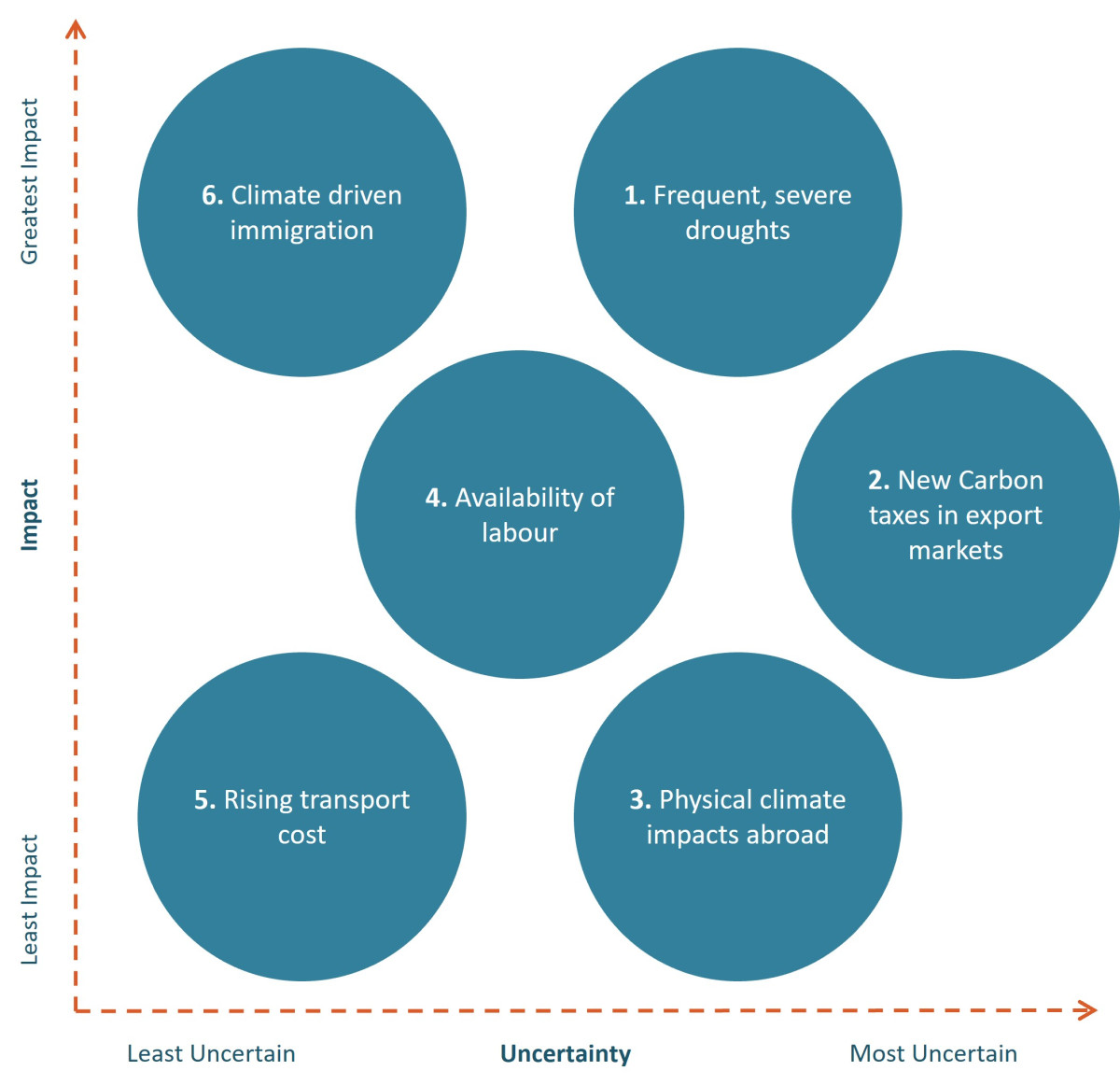

Impact is the degree of potential impact of the driver to the organisation (materiality). Uncertainty is the degree of uncertainty pertaining to a driver and how it will manifest. You may wish to rank driving forces on axes of least uncertain to most uncertain and least impact to greatest impact.

To determine the most appropriate parameters for the scenarios it is necessary to identify the drivers that generate critical uncertainties in the future.

Diagram shows driving forces plotted on axes of impact and uncertainty.

The driving forces are:

Diagram shows driving forces plotted on axes of impact and uncertainty.

The driving forces are:

The final selection of driving forces should be pared down to a limited set that is relevant and balanced. Because the driving forces will be used for building the scenarios, the more numerous the forces, the more complicated the scenario-building process. In most cases, scenarios are elaborated with four to eight forces.

This workshop aims to develop plausible outcomes within the scenario archetypes by identifying different future specifications for each of the critical driving forces.

This step starts with identifying the type of outcome that could take place in the future in relation to each selected driving force. From the possible outcomes for each driving force, states are developed.

A state is a hypothesis about what could happen to a driving force; it is a qualitative description of the driving force in the future at the selected time horizon. For each driving force, the states must be contrasted and mutually exclusive, meaning that two states cannot happen simultaneously within a given scenario. On completing this exercise, the result will be a collection of outcomes for each of the material and highly uncertain drivers, within each archetype. These draft scenarios form the basis for the final scenario narratives.

This workshop generates basic parameters for scenario narratives that can be shared for review and comment with the scenarios team and workshop participants.

The basic scenario architecture consists of the underlying storylines, trends and assumptions for each archetype, and the outcomes from the previous workshop.

The output of this step is draft scenario narratives that can be shared for review and comment with the scenarios team and workshop participants.

In this phase, the scenarios should be formulated, and narratives produced to help visualise and synthesise a range of plausible yet divergent futures. The narratives should follow the concept of staged access: overview ought to come first, and details shall follow on demand.

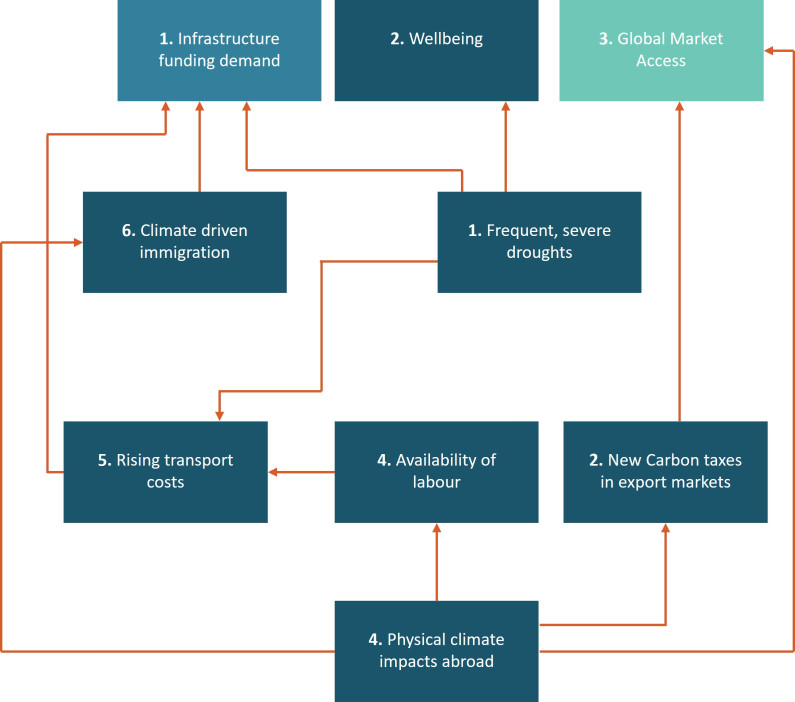

Before writing the scenario narratives, you may find it useful to draw a conceptual model of how driving forces and critical uncertainties interact under each scenario.

This conceptual model is an example of how driving forces and critical uncertainties interact under each scenario.

The driving forces and critical uncertainties shown are:

Begin drafting the scenario narratives by putting together a single paragraph with the full description of the states of driving forces corresponding to each scenario. The scenarios assume the top ranked driving forces occur and have material impacts which unfold in different ways across the archetypes.

Use the same structure across the scenarios’ narratives to begin drafting a coherent story. Driving forces that have high impact but lower levels of uncertainty can provide a common baseline to all the narratives.

For each scenario, keep in mind the scenario baseline and progressively complete the story by adding compatible states of the other driving forces. Each overall scenario narrative will represent a set of interrelated future events and states that may occur under the explicitly stated baseline conditions.

A short summary (200 words) for each scenario can capture most of the relevant points. These summaries can be accompanied by longer, more detailed discussion about each category.

In order to assess the quality of the final scenarios, the following key criteria can be applied:

|

Factor |

Check the scenario has* |

|---|---|

|

Plausible |

Events unfold in a manner that is possible and credible in the eyes of decision makers. |

|

Distinctive |

Differing assumptions about the interplay of driving forces under each scenario, with a sufficient number of scenarios produced to appropriately explore a range of outcomes. |

|

Consistent |

Application of the scenario logic is consistent between scenarios. |

|

Relevant |

Insights into the future evolution of climate-related risks and opportunities that directly relate to the strategic decisions an entity must take. |

|

Challenging |

Sufficiently challenge conventional wisdom and avoid falling into simplistic extrapolation of present conditions into the future. The scenarios need to help to evaluate the performance of the business model and strategy under difficult circumstances to be of greatest value. |

*Definitions taken from Staff Guidance Entity Scenario Development [External Reporting Board website]

The scenarios must provoke and challenge current mental maps in the minds of stakeholders or the public. But the scenarios should also not be fairy tales or science fiction stories either. Instead, they should describe plausible futures.

Several drafts may be needed to strike the balance between structured iteration, and an open and creative process.

The output of this step is competed scenario narratives ready to be applied to your situation or policy.

The completed scenarios should include:

The completed scenarios will provide plausible future versions of Aotearoa New Zealand in relation to the focal question and over the specified time frame(s).

The scenarios should not claim to predict or project what the future may look like. Rather, they should be plausible futures that can serve as a ‘test’ for navigating through uncertainty, ambiguity, and novelty for policy and decision makers.

The scenarios are a forward-looking framework that provide a reference for use in debates about potential futures.