PART A: Explanatory material to the exposure draft of the Natural and Built Environments Bill

1. The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is New Zealand’s main law governing how people interact with natural resources. As well as managing air, soil, freshwater and the coastal marine area, the RMA regulates land use and the provision of infrastructure, which are integral components of our resource management system. People can use natural resources if doing so is allowed under the RMA or permitted by a resource consent.

2. The RMA has not delivered on its desired environmental or development outcomes, nor have RMA decisions consistently given effect to the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti/the Treaty). Current processes take too long, cost too much and will not address the many new challenges facing our environment and our communities.

3. Aotearoa New Zealand needs a resource management (RM) system that will manage these challenges more effectively for current and future generations. The RM system needs to transform our relationship with the environment and better enable development and infrastructure. The design of the new RM system needs to learn from the past and produce better results.

4. In February 2021 the Government announced it would repeal and replace the RMA, based on the recommendations of the Resource Management Review Panel (the Panel, as described in paragraph 6 below). The three proposed Acts are the:

5. Various groups have called for comprehensive RM reform. There have been numerous reviews of the RM system, including by the Environmental Defence Society, central and local government, commissions, non-governmental organisations and Māori groups. For a list of relevant reviews and reports, see page 510 of the Panel’s report. Since that report, a collation of Waitangi Tribunal findings on the RMA has been republished. Other groups calling for reform include the Federation of Māori Authorities, the New Zealand Māori Council, and Kāhui Wai Māori; and (supporting the Environmental Defence Society) Property Council New Zealand, Infrastructure New Zealand, and Employers and Manufacturers Association (Northern).

6. In response, in July 2019 the Government appointed the Resource Management Review Panel to carry out an expert review of the current RM system, including a review of the RMA.

7. The Panel undertook the most significant, comprehensive and inclusive review of the RM system since the RMA was enacted. It was chaired by former Court of Appeal Judge, Hon Tony Randerson QC, and its other members were Rachel Brooking, Dean Kimpton, Amelia Linzey, Raewyn Peart and Kevin Prime.

8. The Panel’s thinking was informed by consultation with Te Tiriti partners, experts and stakeholders. It built on previous reviews and reports as noted above.

9. The Panel’s report New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand was released in July 2020 and is available online. It identified systemic issues in resource management and made comprehensive recommendations for reform. The summary and the full Panel report, as well as more information about the members and the review process, are on the Ministry for the Environment’s website.

10. The Panel’s report is guiding the next steps in this transformative change.

11. The Government’s reform objectives are listed in the table below, which maps issues with the RMA against these objectives. Meeting the objectives will be achieved through all three proposed Acts, which will work together as a package.

12. For more information about issues with the RMA, see the interim regulatory impact statement for the NBA exposure draft.

| Status quo | Reform Objectives | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Natural environment under significant pressure and degraded through unsustainable use, eg 4000 native species under threat | Protect and where necessary restore the natural environment, including its capacity to provide for the well-being of present and future generations |

| 2 | Planning and infrastructure constraints to development contribute to high costs of land and housing relative to median incomes. National Policy Statement on Urban Development yet to be implemented | Better enable development within environmental biophysical limits including a significant improvement in housing supply, affordability and choice, and timely provision of appropriate infrastructure, including social infrastructure |

| 3 | The RMA Treaty clause is to ‘take into account’ the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) | Give effect to the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and provide greater recognition of te ao Māori, including mātauranga Māori |

| 4 | Despite increasing extreme events, development is still occurring in high-risk places, with uncertainty about cost and who pays for adaptation, and ad hoc decisions about retreat | Better prepare for adapting to climate change and risks from natural hazards, and better mitigate emissions contributing to climate change |

| 5 |

Estimated costs of $100m per annum borne by resource users and councils.

Councils make most decisions, subject to some national direction and Environment Court appeals.

Low participation; submissions and appeals focus on site-specific impacts; Māori, women, younger people, and renters are under-represented. |

Improve system efficiency and effectiveness, and reduce complexity, while retaining appropriate local democratic input |

13. To deliver the NBA, the Natural and Built Environments Bill (the Bill) is being progressed in a two-stage select committee process. The first stage is the select committee inquiry into a partial draft of the Bill, ie the exposure draft. The second stage will be a standard legislative process for the full Bill next year.

14. More information on the policy intent behind the changes proposed in the Bill is provided in the rest of Part A of this paper, explanatory material, along with the wider context for the reform. This material has been prepared to help people better engage with the exposure draft.

15. Part B of this paper presents the exposure draft. The exposure draft does not cover the full Bill, but provides an early look at key aspects, including:

16. The exposure draft is the main focus of the select committee inquiry. The select committee will examine the draft with reference to the reform objectives, and seek feedback on the exposure draft from the public. The scope of the inquiry is set out in the Terms of Reference (Appendix 1).

17. The Terms of Reference also invite the select committee to consider ideas for reducing the complexity of the RM system – as the reform will only be successful if it results in a more efficient system. A list of ideas for increasing efficiency and reducing complexity, partially based on ideas received via the Panel’s review, is attached as Appendix 2 to help prompt thinking.

18. At the end of the inquiry, the select committee will publish a report. The Government will then consider the report and the feedback from submitters.

19. For information on the submission period for the inquiry and how to submit, see more about the exposure draft for the Natural and Built Environments Bill.

20. The Panel considered the interactions between the RMA, Local Government Act 2002, Land Transport Management Act 2003, and Climate Change Response Act 2002. These other acts are key parts of the RM system, but there are also other relevant pieces of legislation, such as the Conservation Act 1987 and Building Act 2004. Substantive changes to these other Acts are not proposed as part of this reform.

21. RM reform links into many other Government programmes. For example, this reform will influence, and be influenced by, current Government work on three waters, freshwater allocation reform and addressing Māori rights and interests in freshwater, climate change, biodiversity, housing and social infrastructure, and the future for local government.

22. Treaty settlements have led to many RM arrangements that recognise the unique relationships between tangata whenua and te taiao (the environment), and help councils meet their responsibilities to iwi and hapū.

23. The RMA interfaces with over 70 Acts and their associated deeds of settlement. Engagement with those iwi and hapū who have settlements or other RM arrangements will be important to ensure reform will both avoid unintended consequences for Treaty settlements, and uphold the integrity of Treaty settlements and agreements under the RMA between councils and Māori; as well as for:

24. Treaty settlement negotiations linked to the RMA will continue while the NBA is developed. The local and specific nature of these arrangements means duplication of NBA provisions is unlikely. The Government will continue to consider how arrangements under negotiation can be transitioned into the new system.

25. The exposure draft does not preclude any options for addressing freshwater rights and interests and their consideration as part of the ongoing discussions with iwi, hapū, and Māori.

26. See Appendix 3 for more information on engagement with iwi, hapū, and Māori groups.

27. This section sets out more information on the proposed legislation to replace the RMA. It draws heavily on the Panel’s report, which recommended repealing the RMA and replacing it with the NBA, SPA and CAA.

28. Appendix 4 provides a summary of the Panel’s recommendations on topics covered in the exposure draft of the NBA, and describes whether and how the exposure draft differs from the recommendations.

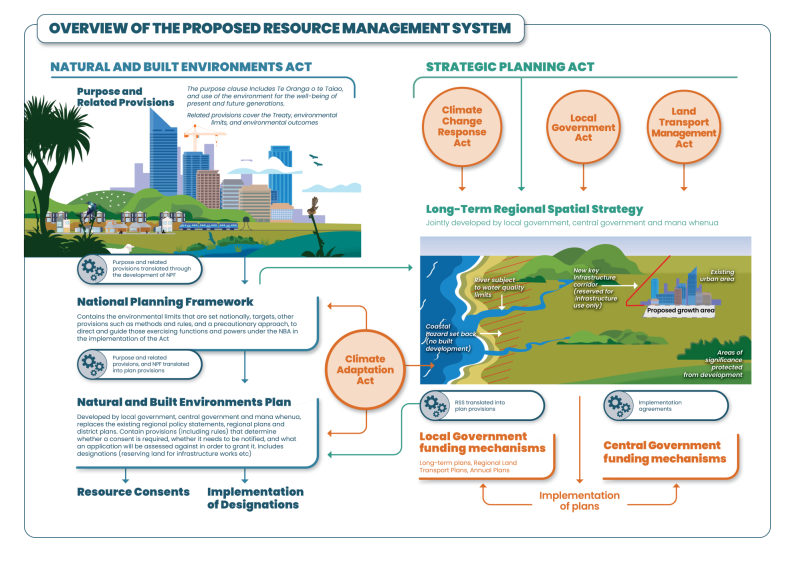

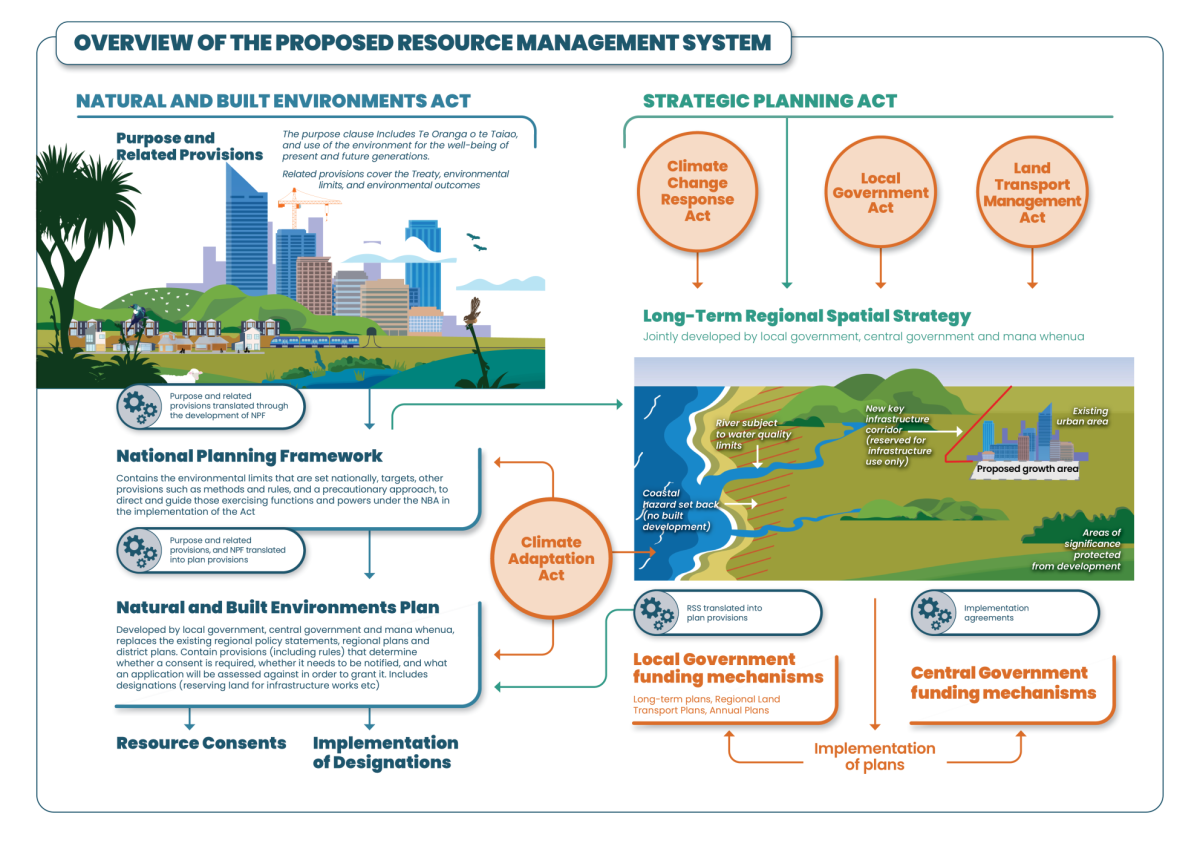

29. Although this paper does not present an exposure draft of the SPA or the CAA, their policy direction is signalled to provide context about the reform as a whole. The following diagram provides an overview of the new RM system.

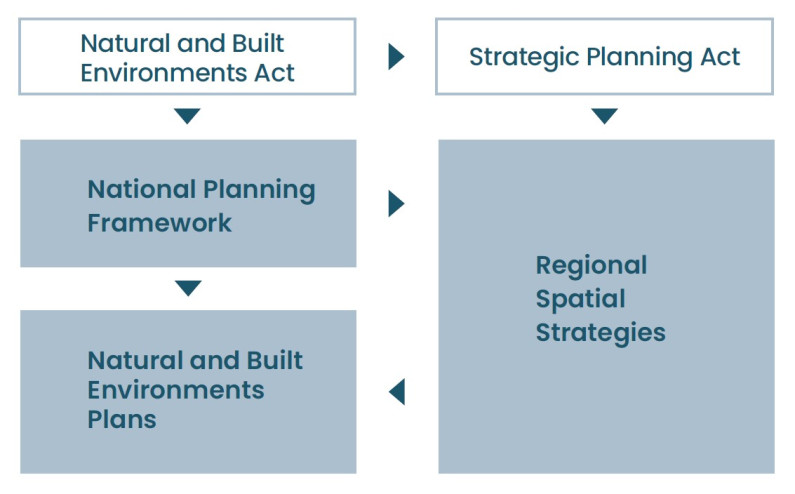

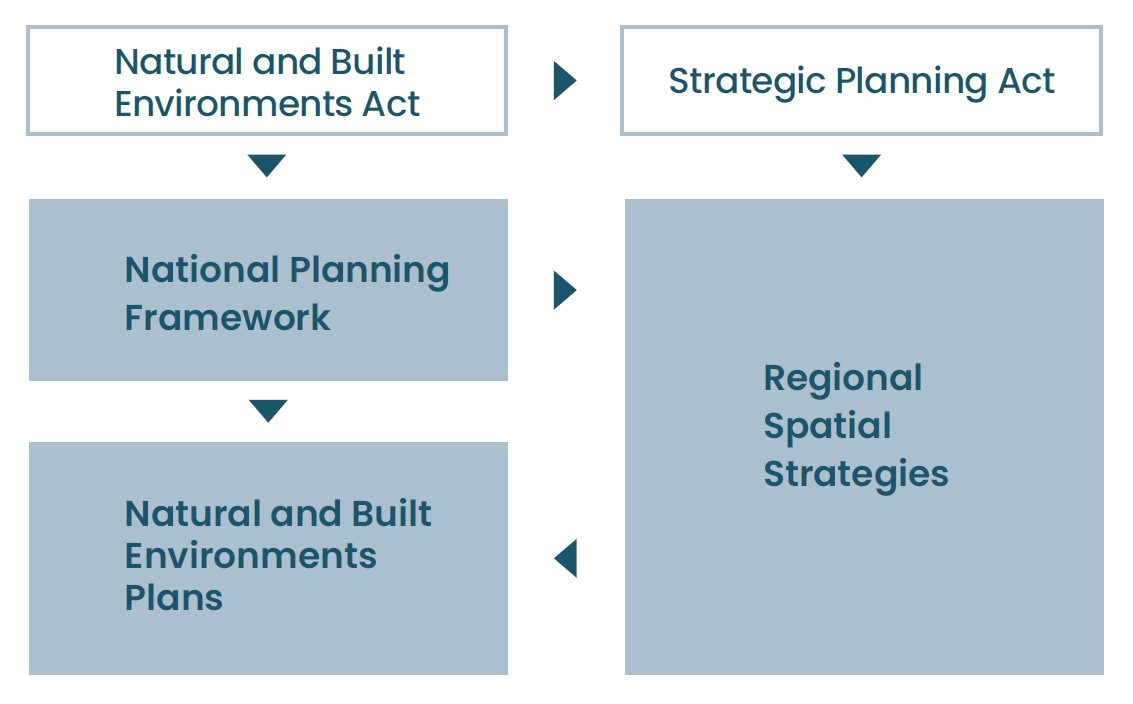

30. As the primary replacement for the RMA, the NBA will address the most significant weaknesses in the current RM system. Like the RMA, the NBA will be an integrated statute for environmental protection and land use. The NBA will work in tandem with the proposed Strategic Planning Act (SPA).

31. The Panel considered a split approach, with one statute governing environmental protection and outcomes, the other for planning, land use and development – but this was not favoured by the Panel. Although the RMA has not brought desired outcomes, an integrated approach is not the problem, and the case for integration remains strong.

32. A major criticism of the RMA is that it has not adequately protected the natural environment. One reason is that national and local RM policy and plans have not always set controls that are strong and comprehensive enough, such as environmental bottom lines.

33. The NBA will include a mandatory requirement for the Minister for the Environment to set environmental limits for aspects of the natural environment, to protect its ecological integrity and human health. These limits will be framed as a minimum acceptable state of an aspect of the environment, or a maximum amount of harm that can be caused to that state. Timing and transitional arrangements will be taken into account in setting limits.

34. Another criticism of the RMA is that it focuses too much on managing adverse effects on the environment, and not enough on promoting positive outcomes across all aspects of well-being. The NBA will specify a range of outcomes that decision-makers will be required to promote for natural and built environments.

35. Outcomes specified in the exposure draft include environmental protection, iwi and hapū interests, cultural heritage, protection of customary rights, housing, rural development, infrastructure provision, and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

36. Outcomes will also guide regional spatial strategies under the SPA.

37. The NBA will carry over the RMA’s requirement to ‘avoid, remedy, or mitigate’ adverse effects of activities on the environment. This will ensure a management framework exists for all adverse effects, including those not covered by limits or outcomes.

38. The NBA will also ensure that measures to avoid, remedy or mitigate effects do not place unreasonable costs on development and resource use. Although the NBA will intentionally curtail subjective amenity values, this will not be at the expense of quality urban design, including appropriate urban tree cover.

39. The NBA intends to improve recognition of te ao Māori and Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

40. To better recognise te ao Māori, Te Oranga o te Taiao will be included in the Act’s purpose. This concept is intended to encapsulate the intergenerational importance of the health and well-being of the natural environment. See paragraph 95 below for what Te Oranga o Te Taiao incorporates.

41. Decision-makers would be required to ‘give effect to’ the principles of Te Tiriti, replacing the current RMA requirement to ‘take into account’ those principles.

42. Under the NBA, the new National Planning Framework (NPF) will provide strategic and regulatory direction from central government on implementing the new system. This will be much more comprehensive and integrated than the RMA required.

43. The NPF will play a critical strategic role, setting limits and outcomes for natural and built environments, and ways to enhance the well-being of present and future generations. Where possible, the NPF will resolve conflicts, or give direction on resolving conflicts across the system.

44. The exposure draft has adopted the Panel’s proposal to develop one NBA plan per region, prepared by a plan committee comprising representatives from local government (regional and territorial), central government (Minister of Conservation), and mana whenua. The Government is still considering the best approach to NBA plan preparation and decision-making, and feedback received from the select committee inquiry will provide valuable input into this.

45. The intention is to consolidate over 100 RMA policy statements and regional and district plans into under 20 plans, simplifying and improving integration of the system.

46. It is important that the reformed RM system supports environments where people can choose to live close to employment, education, health and recreation, and the opportunities they provide. This will allow communities to develop in ways that support the prosperity and well-being of their people, enable social and cultural connections, and minimise environmental impact.

47. Through a more constructive and coherent influence on regional spatial strategies and NBA plans, the NPF will improve certainty for developers, local government, infrastructure providers and the community. It will provide strategic and regulatory direction and guidance (eg on infrastructure or zoning rules), increasing the consistency of plans.

48. Infrastructure is recognised in the purpose and related provisions of the exposure draft, as a mandatory topic in the NPF, and for consideration in NBA plans. The integration of decisions on land-use planning with the delivery of infrastructure and its funding is a key reason for the SPA as described below. Policy work will continue while the select committee is conducting its inquiry.

49. The proposed Strategic Planning Act (SPA) is a critical part of the reform, and will be a new addition to the RM system. The SPA will mandate strategic spatial planning and bring together outcomes and functions across several statutes to achieve a longer-term and integrated approach to land use and infrastructure provision, environmental protection and climate change matters. This would extend into the coastal marine area.

50. The Panel proposed that the purpose of the SPA should be “to promote the social, economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing of present and future generations through the long-term strategic integration of functions exercised under specified legislation.” (New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand, page 490.)

51. The Panel also proposed that the SPA include a Te Tiriti o Waitangi clause, based on the clause agreed for the NBA.

52. Regional spatial strageies (RSSs) were recommended by the Panel. They will be a key mechanism in the RM system requiring local government, central government and iwi, hapū and Māori, and to take a joined-up strategic vision of the future. This is about identifying the big issues and opportunities facing a region and identifying how it will grow and change over the next 30 plus years. RSSs will provide a clear strategic direction to decision-makers.

53. RSSs will be high-level and strategic and focus on the major issues and opportunities for a region. If too detailed, they would duplicate NBA plans and add complexity to the system.

54. RSSs will:

55. RSSs will need to be informed by robust information and evidence, including mātauranga Māori, that is proportionate to the level of detail required. RSSs will also need to uphold relevant Treaty settlements and customary rights.

56. RSSs will need to integrate with other relevant documents. For example, they will need to translate national-level direction, such as that contained in the NPF, into a regional context and provide strategic direction for NBA Plans and local authority funding plans. This will be covered in the Strategic Planning Bill, together with governance and decision-making on RSSs. The Bill will be introduced to Parliament with the full Natural and Built Environments Bill.

57. Aotearoa New Zealand’s communities, assets, infrastructure and taonga are increasingly exposed to the risks and impacts of natural hazards and climate change. Development has occurred in areas where there is, or is likely to be, high risk to life or property. Pressure is growing for new development in at-risk areas. If nothing is done, the number and likelihood of these risks and the costs to address them will continue to increase.

58. The Panel proposed the Climate Adaptation Act (CAA) as specific climate change adaptation legislation to address the complex legal and technical issues associated with managed retreat and funding and financing of adaptation. A central goal of the CAA will be to incentivise action now, to reduce future cost and distress.

59. The Panel noted that managed retreat is particularly challenging. It is a risk management response option for climate change adaptation and natural hazard risks. Managed retreat enables people, where possible, to relocate assets, activities, and taonga away from hazardous locations (eg areas at risk from coastal flooding). The aim is to enable retreat away from areas where the effects of climate change or other natural hazard risks are likely to be so severe that withdrawal is the preferred option.

60. Apart from managed retreat, the wider RM system (including the NBA and SPA) and the National Adaptation Plan under the Climate Change Response Act (CCRA) offer other tools for adaptive responses to natural hazards and climate change impacts. Some examples include:

61. As the CAA, NBA and SPA are further developed, consideration will need to be given to clear roles and responsibilities across the three pieces of legislation to enable effective adaptation and risk management responses.

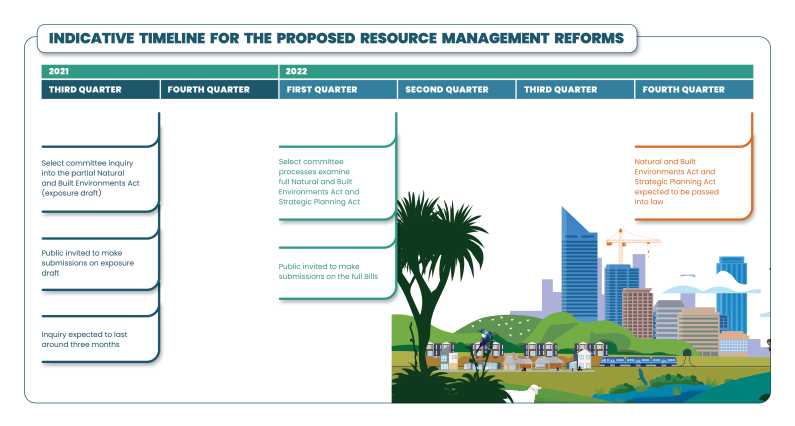

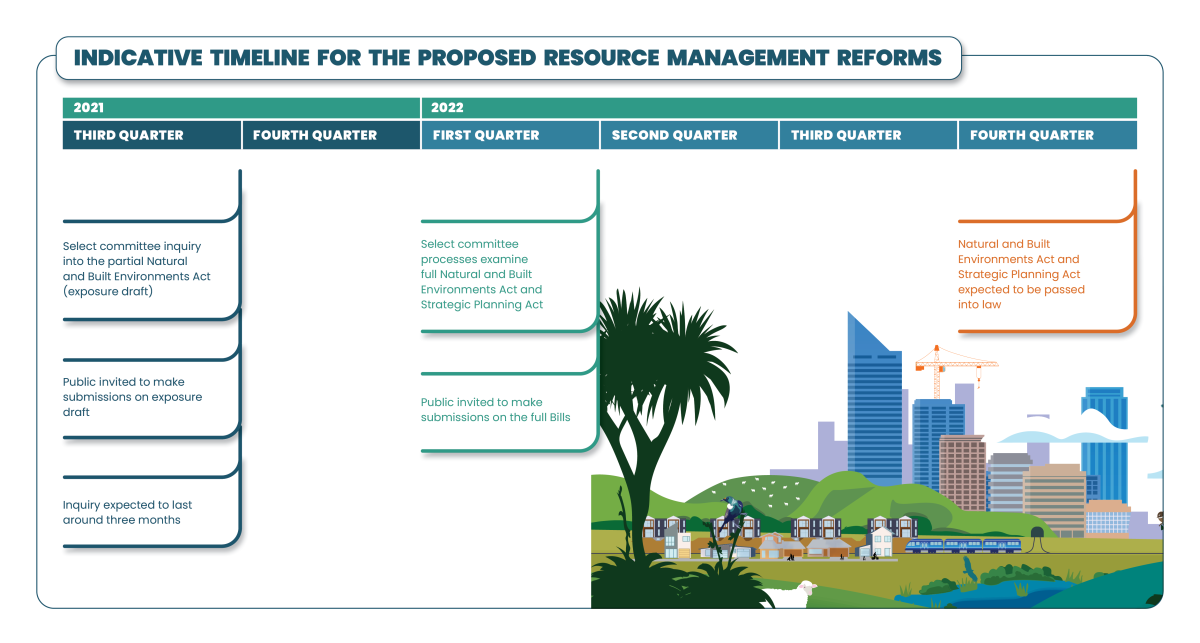

62. The outcome of the select committee inquiry will feed into our work on the NBA, and inform the other Bills. After the three Bills are introduced to Parliament, there will be an opportunity to submit on them through the usual select committee process.

63. The intention is for the NBA and the SPA to be introduced to Parliament in early 2022, follow the standard legislative process, and be passed before the end of the current Parliamentary term, including three readings in the House and a standard select committee process. [New Zealand Parliament website]

64. The core policy to be included in the CAA will be consulted on in early 2022 alongside consultation on the National Adaptation Plan under the Climate Change Response Act. This will allow for policy coherence across the response to the National Climate Change Risk Assessment, as well as coherence with the NBA and SPA. The CAA will be developed after considering the results of consultation, with the intention that legislation will be introduced to Parliament in early 2023.

65. See the timeline below for indicative dates for the reform programme.

66. A well-planned and well-executed establishment of the new system is essential. We have learned important lessons from how poor implementation of the RMA has contributed to poor environmental and urban development outcomes.

67. For the new RM system to have the best chance of working well, key elements such as the NPF must be in place as early as possible. Innovation and digital technologies will also be integral to transforming the system (eg planning, centralised data platforms, and web portals). Central government will also need to play a greater role in the new system.

68. All levels and all players in the system will need to have in place the capability and capacity to deliver the reform objectives. Culture change will be essential to the transformation required.

69. The Government will work with local government and Te Tiriti partners ahead of and during the transition, to establish enduring relationships and ensure support is in place, particularly as the new NBA plans and RSSs are developed. The Government is providing substantial funding for implementing the reform and establishing a well-functioning new system, including the guidance, processes, and tools required.

70. In the meantime, momentum must be maintained in addressing current environmental and planning challenges. The Government expects councils to continue working on the requirements of the RMA and current national direction. The development of the NPF is intended to capture the policy intent of existing national direction, align it with the new legislation, and determine how to fill in gaps.

71. Providing as much certainty about how the legislation will work in practice is critical to the success of the reform. It is important that management decisions are made with a clear understanding of the values and associations that different people hold in relation to the environment, and how these are relevant to particular decisions under consideration (including for plans and consents). It may be helpful to clarify this in the legislation.

72. The NBA will include transitional provisions that take account of existing processes, but these are not included as part of the exposure draft.

73. The exposure draft of the NBA contains key elements of the Bill to test with the public. This section explains the clauses in the exposure draft, and notes key elements that are still to come. Feedback on the exposure draft will help shape the full Bill.

74. The table below summarises what is in the exposure draft, and therefore the focus of the select committee inquiry. It also notes matters that are not included in the exposure draft, but will be in the full Bill.

| Included in the exposure draft | Not included* |

|---|---|

|

*This is not a complete list and does not represent what these matters may be called in the new system |

75. Placeholders are used in the exposure draft to signal clauses that can be expected in the full Bill and where they might fit. For example, clause 17 is a placeholder for the links between the CCRA and the NBA. How best to create those links is still being decided, and will be explored alongside work on emissions budgets, the Emissions Reduction Plan, and National Adaptation Plan. Also, clause 17 is a placeholder for the role of the Minister of Conservation in relation to the National Planning Framework (NPF). Under the RMA, that Minister takes the lead in preparing the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement.

76. This section explains each clause (or related group of clauses) in the exposure draft. It also notes what is not included in the exposure draft, in relation to each part of the draft.

77. Clause 1 is the Title clause.

78. Clause 2 provides for the Act coming into force. Parts of the Act may come into force at different times.

79. These preliminary provisions include the Act’s key definitions (the ‘interpretation’ section), and a placeholder for how the Act will bind the Crown.

80. Clause 3 provides definitions for terms used in the Bill.

81. Clause 3 only includes the definitions used in the exposure draft. The full Bill will have a wider set of definitions for terms used elsewhere.

82. Clause 4 is a placeholder for how the Act binds the Crown.

83. The intent of clause 4 is that the new Act will bind the Crown. Decisions on any specific exceptions to this, such as those in sections 4(2) to 4(12) of the RMA in relation to specific entities or activities, will come in the full Bill.

84. The purpose and related provisions of the NBA include:

85. These provisions will be located at the front of the Act, to set the context and key direction for the provisions that follow.

86. On a site-by-site basis, environmental protection and development goals are sometimes at odds. An important role for the system is to enable people and communities to weigh competing objectives and make decisions.

87. Good planning can raise environmental standards as well as ensure there is sufficient housing and infrastructure to service a growing population. The system needs to recognise and encourage synergies between development and environmental protection. For example, more renewable electricity generation requires new infrastructure such as wind farms.

88. A key consideration for the NBA will be how much active planning is needed to achieve outcomes for natural and built environments. The main focus of the RMA was (at least in practice) primarily on managing adverse effects. The NBA is designed to give central government, with iwi, hapū and Māori, a larger role in promoting activities and uses to achieve positive outcomes.

89. Clause 5 sets out the purpose of the NBA, which is to enable:

90. To achieve the purpose:

91. The purpose of the NBA aims to improve on the RMA in two key ways:

92. Upholding Te Oranga o te Taiao and being more explicit about the intrinsic relationship between iwi, hapū and te Taiao also better reflects te ao Māori within the system.

93. The Panel proposed recognition of the concept of Te Mana o te Taiao, as part of the purpose statement. The Panel proposed that this concept outline the core aspects of the natural environment that must be maintained to sustain life.

94. The inclusion of a concept that draws on te ao Māori contributes to the reform objective to “give effect to the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and provide greater recognition of te ao Māori, including mātauranga Māori”, as well as contributing to other reform objectives, including the objective to “protect and where necessary restore the natural environment, including its capacity to provide for the well-being of present and future generations”.

95. The Government has explored whether 'Te Mana o te Taiao' was the tika (right/correct) concept to use, whether ‘recognise the concept’ was the right statutory weighting to use, and whether the definition of Te Mana o te Taiao as suggested by the Panel was appropriate. Various alternatives that addressed these questions were presented to Ministers.

96. Te Oranga o te Taiao was suggested by the Freshwater Iwi Leaders Group (FILG) and Te Wai Māori Trust (TWMT). These are two of the Māori groups the Government has engaged with (see Appendix 3 for more information). In their view, Te Oranga o te Taiao more appropriately reflected a te ao Māori approach and encapsulated the intergenerational importance of the health and well-being of the natural environment. FILG and TWMT felt that 'Te Mana o Te Taiao', as articulated and defined by the Panel, did not adequately reflect or embrace a te ao Māori view, including the innate whakapapa-based relationship between iwi, hapū, Māori and te Taiao.

97. For the purpose of the NBA, the definition of Te Oranga o te Taiao incorporates:

98. Importantly, Te Oranga o te Taiao is not being advanced as a standalone proposition within the purpose of the NBA. As with 'Te Mana o te Taiao', it is intended to be connected to, and supported within, other NBA provisions that provide for the better alignment of the RM system to Te Tiriti o Waitangi and te ao Māori. This includes environmental outcomes and implementation principles.

99. Feedback is sought on Te Oranga o te Taiao through the select committee inquiry process. Officials will also continue to work on the concept and its implementation with iwi, hapū and Māori groups (and on any modifications or alternatives advanced).

100. The term ‘outcomes for the benefit of the environment’ includes, but is not limited to, ‘environmental outcomes’ listed in clause 8.

101. Clause 6 provides that all persons exercising powers and performing functions and duties under the NBA must give effect to the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi.

102. This will be a ‘general effect’ Treaty clause.

103. The requirement to ‘give effect to’ the principles of the Te Tiriti reflects the importance of the environment to Māori, the Crown’s obligations under the Te Tiriti to iwi and hapū in relation to the environment, and the importance of the Treaty partnership in resource management.

104. Compared to the RMA’s ‘take into account’ Treaty clause, those with powers and functions under the NBA will have a stronger and more active duty to give effect to the principles of Te Tiriti.

105. The requirement to give effect to Te Tiriti will be realised in the new system through mechanisms like participatory rights in preparing NBA plans and RSSs, and the expectation that iwi management plans are used in the preparation of NBA plans. Decision-making is expected to be consistent with the principles of Te Tiriti.

106. ‘Te Tiriti o Waitangi’ will be defined (consistent with the RMA and the Panel’s recommendation) to mean the same as ‘Treaty’ in the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, where Treaty means the Treaty of Waitangi as set out in both English and in Māori in Schedule 1 of that Act. Consequently both the English and Māori texts are referenced in this clause. As the Panel noted, referring solely to Te Tiriti o Waitangi in the NBA “will not affect the legal application of the term” but is “an important symbolic step”. (New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand, page 76 (paragraph 119), page 101 (paragraph 68)).

107. Clause 7 states that environmental limits must be prescribed through the National Planning Framework (NPF), or in NBA plans in accordance with any requirements set out in the NPF. The purpose of these limits is to protect the ecological integrity of the natural environment and human health.

108. Environmental limits may be formulated as either:

109. Environmental limits must be prescribed for at least these matters:

110. The requirement to prescribe environmental limits through the NPF is pivotal to achieving the purpose of the Act. These limits will make a key contribution to protecting the ecological integrity of the listed matters and human health.

111. There will be discretion to prescribe limits for other natural environment matters outside of those listed.

112. Limits could be set in two forms, describing:

113. Limits will need a degree of sophistication drawing on a range of knowledge sources (including mātauranga Māori), some of which may have imperfect data or are not easy to quantify. The Bill will therefore provide for limits to be qualitative (descriptive) as well as quantitative (set using numbers). Limits will take a precautionary approach (and therefore incomplete or uncertain data should not be a barrier to setting limits).

114. Clause 8 states that the NPF and all plans must promote environmental outcomes on the following topics:

115. An outcomes-based approach works for both protecting resources (eg biodiversity) and enabling activities (eg housing and infrastructure) and responds directly to the needs of communities in each region to resolve tensions. An outcomes-based approach founded in Part 2 of the NBA will require planning practice to shift from solely focusing on managing adverse effects.

116. The NBA outcomes are to be long-term and enduring. The detail on how this will be achieved will be set out in the NPF and NBA plans. This includes development of targets, use of regulation, and other tools like economic instruments (environmental taxes and charges).

117. It is a significant shift to focus on outcomes, and providing for these in the NPF and NBA plans. Being clear about outcome delivery should improve the performance of the regulatory system and the accountability of decision-makers for its results.

118. The NBA will promote the well-being of both urban and rural areas. In relation to rural areas, an outcome (clause 8(m)) is for development to be pursued that:

119. The role of the environmental outcomes in guiding decision-making about resource consents, designations and other approvals under the NBA is yet to be decided and is not addressed in the exposure draft.

120. An important role for the resource management system is managing conflicts between competing objectives, particularly between the use and protection of the environment.

121. The exposure draft has the following measures to clarify how to resolve potential conflicts:

122. The strong emphasis on setting environment limits, and the mandatory content required in the NPF, will help resolve potential conflicts. More comprehensive plans will also help address conflicts between different outcomes; for example, classifying more activities as either ‘permitted’, or ‘prohibited’ in NBA plans or national direction.

123. Conflicts between outcomes will inevitably arise in consenting decisions, including in ways that plans do not cover. It will not be feasible for the NPF and NBA plans to foresee and conclusively resolve all tensions in advance, but the full Bill will provide mechanisms for decision-makers to resolve conflicts at the consenting stage.

124. The Panel proposed a number of duties on the Minister for the Environment to give national direction on limits and outcomes. Most of these duties are now reflected in mandatory requirements for the content of the NPF. An important exception is the Panel’s proposal for national direction on how to give effect to the principles of Te Tiriti. It is instead intended that guidance and direction on this will be contained in further provisions of the NBA.

125. Part 2 does not define targets, or what they will be set for, or how they will be applied to different places and circumstances. These matters will be determined through the process of developing the NPF.

126. While the NBA outcomes include the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, further work is underway to explore how the NBA can be used to make progress towards achieving New Zealand’s emissions reduction goals under the CCRA.

127. The National Planning Framework (NPF) will be the tool under the NBA for strategic and regulatory direction from central government on the use, protection and enhancement of the natural and built environments in the interests of all New Zealanders. The NPF will:

128. Clause 9 establishes that there must at all times be an NPF. The Minister for the Environment must prepare and maintain the NPF in the manner described in Schedule 1. The Bill will contain transitional provisions to address how this requirement applies to the preparation of the first NPF.

129. Clause 10 states that the purpose of the NPF is to help achieve the purpose of the NBA, by providing integrated direction on matters of national significance or matters where national or sub-national consistency is desirable.

130. The RMA largely devolves decision-making about resource management and land use to local authorities. However, central government can give policy direction, set standards and methods, and prescribe regulatory plan content. Under the RMA, this is done using various instruments including: national policy statements, national environmental standards, national planning standards, and other regulations.

131. Under the RMA, national policy statements are able to include content such as ‘development capacity’ requirements in the National Policy Statement on Urban Development or the national target in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 that 90% of specified rivers and lakes are suitable for primary contact by 2040.

132. The Panel recognised the important role of direction from central government on matters of national importance, and recommended that the set of national direction be integrated, with conflicts between instruments resolved. This latter point is key, as one criticism of the RMA is that limited, and sometimes apparently conflicting, national direction has led to inconsistent policy in RMA plans, and unresolved conflict between national priorities.

133. The NPF will provide:

134. The NPF will also provide direction on resource management matters that must be consistent throughout the system. This may include methods, standards and guidance to support spatial strategy and plan-making processes. It should also make planning and consenting faster and more efficient.

135. Clause 11 states that the NPF will have the effect of regulations. The regulations that make up the NPF may apply throughout New Zealand or to specific locations, specific classes of people, and specific periods. The regulations may set directions, policies, goals, or methods; or provide criteria, targets, or definitions.

136. The NPF will be made as regulations. It will be secondary legislation under the NBA, and will be a disallowable instrument. A disallowable instrument is a type of secondary legislation that is subject to review by the Regulations Review Committee (a select committee with proportional representation from across the House). Parliament has the power to ‘disallow’ an instrument, so that it will cease to have effect, where certain criteria apply.

137. Secondary legislation allows direction to be updated over time as the state of the environment changes, and as new and unforeseen issues arise.

138. Clause 12 provides that the NPF may set limits directly or may prescribe a process for planning committees to determine limits.

139. Environmental limits may be prescribed:

140. The NPF is the main vehicle for setting environmental limits. It will be mandatory for the NPF to set limits on the matters set out in clause 7 (eg air, biodiversity, coastal waters, estuaries, freshwater and soil).

141. The Minister for the Environment would be responsible for setting NPF limits and processes.

142. The provision allows for flexibility, which acknowledges that limits will need to provide different levels of environmental protection to different circumstances and locations.

143. There should be strong links between limits and other instruments in the NPF and plans that would manage harmful activities. For example, between a limit and the planning controls that restrict land use or development causing unacceptable harm; or economic instruments that could help allocate scarce resources.

144. Clause 13 sets out the topics that the NPF must include:

145. The NPF may also include provisions on other topics outside this list if they accord with the purpose of the NPF.

146. In addition, the NPF must include provisions to help resolve conflicts relating to the environment, including between environmental outcomes.

147. This section sets out mandatory topics on which the Minister must provide direction through the NPF.

148. Under the RMA, the only mandatory requirements for national direction are for the New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement and the minimum requirements for national planning standards.

149. The Panel recommended (pages 76-79 of its report) a broader suite of mandatory national direction under the NBA, on 21 matters including:

150. The list in clause 13 for mandatory direction in the NPF is intended to ensure the development of central government direction is prioritised for matters that are critical to achieving the NBA’s purpose, and matters for which direction is most needed to support timely development of RSSs and NBA plans. In addition, the policy intent of existing national direction instruments will be consolidated and integrated with the NPF. The Minister will also have discretion to provide direction in the NPF on topics outside this mandatory list that accord with the purpose of the NPF.

151. The Panel recommended mandatory national direction on Te Tiriti. Instead, it is intended to provide direction and guidance in the legislation itself on how to implement clause 6 (Te Tiriti).

152. In a new outcomes-focused system, central government direction must be more active in setting priorities and helping to manage conflicts across outcomes. The NPF must therefore give direction as priorities, pressures and opportunities change over time. The NPF should provide more considered direction for regional decision-makers who need to reconcile and prioritise competing matters in their communities. The NPF should also integrate with RSSs and NBA plans to ensure system efficiency and achievement of the outcomes sought under both.

153. Clause 14 states that the NPF must include strategic goals such as:

154. The scope and contents of national direction under the RMA differs between the various instruments (ie national policy statements, national environmental standards, national planning standards, and regulations). Current instruments are issued separately. Best practice is to consider how new national direction aligns with existing direction when it is prepared. However, the variety of individually issued instruments under the current legal framework can inhibit integrated management.

155. This will be remedied through the proposal to combine and integrate national direction instruments in the NPF.

156. Clause 15 sets out how NPF provisions will be put into practice.

157. The NPF may direct that certain provisions:

158. The NPF may direct local authorities to amend NBA plans to give effect to regulations, either through a public plan change process, or (if directed) without this process.

159. The NPF will give clear, practical and measurable direction for local authorities and communities. A subsequent process at a regional level may or may not be needed to integrate this direction into a plan in any given case. This approach strikes a balance between enabling central government to efficiently respond to emerging environmental issues, and allowing local input.

160. Clause 16 states that in setting environmental limits, the Minister for the Environment must apply a precautionary approach.

161. The precautionary approach (defined in clause 3) applies where effects on the environment are uncertain or unknown but could cause potentially serious or irreversible harm to the environment. The precautionary approach favors taking action to prevent those adverse effects rather than postponing action because there is a lack of full scientific certainty.

162. Clause 17 is a placeholder for further matters to come. These include:

163. Clause 18 is a placeholder for implementation principles, with placeholders within it. The clause proposes that relevant persons must:

164. The Panel developed a number of implementation principles that it recommended be included in Part 2 of the NBA.

165. Clause 18 provides an example of what general implementation principles could look like. While they would be applied differently depending on the decision in question, having the principles as general requirements would ensure they could always be drawn on when useful in decision-making.

166. Alternatively, the implementation principles could be incorporated as part of specific substantive and procedural decision-making requirements. This would ensure what was required of decision-makers was clear in different circumstances. The table below sets out how the implementation principles have been incorporated into the exposure draft.

167. Further consideration is being given to how the implementation principles can be clearly expressed to best support decision-making in the new system.

| Implementation principle | How principles are reflected in exposure draft |

|---|---|

| Promote the integrated management of the environment |

|

| Recognise and provide for the application, in relation to te taiao, of kawa, tikanga (including kaitiakitanga) and mātauranga Māori |

|

| Ensure appropriate public participation in processes undertaken under this Act, to the extent that is important to good governance and proportionate to the significance of the matters at issue |

|

| Promote appropriate mechanisms for effective participation by iwi and hapū in processes undertaken under this Act |

|

| Recognise and provide for the authority and responsibility of each iwi and hapū to protect and sustain the health and well-being of te taiao |

|

| Have particular regard to any cumulative effects of the use and development of the environment |

|

| Take a precautionary approach |

|

Schedule 1 (referred to in clause 9 of the Bill) is a placeholder for the process to develop the NPF. The process will be included in the full Bill.

168. The process to develop the NPF should provide for direction in all forms, ranging from significant national policy to administrative standards and regulations. This could include using a board of inquiry or independent panel and designing a simplified process for less significant matters.

169. There could be a standing independent body (such as a permanent board of inquiry) that could convene at different times to maintain consistency and integration across different topics in the NPF.

170. The process is intended to provide for:

171. Further work is needed to determine the role for iwi, hapū and Māori in the process and substance of the NPF – in order to give effect to the principles of Te Tiriti and provide greater recognition of te ao Māori, including mātauranga Māori, in the RM system.

172. Further aspects not yet provided for in Part 3 include:

173. These matters will form part of the full Bill (and the Strategic Planning Bill regarding RSSs).

174. Part 4 describes, at a high level, what planning will be like under the NBA. It addresses the role of NBA plans in the system, their relationship to the NPF and regional spatial strategies (RSSs), and what they must achieve.

175. The exposure draft has adopted the Panel’s proposal to develop one plan per region, prepared by a plan committee.

176. Clause 19 states that there must be at all times a natural and built environments plan for each region.

177. NBA plans will further the purpose of the Act by providing a framework of policies, rules, objectives and processes for managing the environment within a region or district. An NBA plan will translate high-level direction from the Act, the NPF and the RSS into local application, to guide decisions on resource use.

178. The existing system of both regional and district plans under the RMA has planning functions split across regional councils and territorial authorities, and has resulted in poorly integrated management across various parts of the environment. This has led to complexity, unacceptable cumulative effects and poor environmental outcomes.

179. One plan per region that covers resource use, allocation and land use management will support integrated management and reduce conflicting policies.

180. This is a significant change as it will require a different model for plan-making and local authority working arrangements, including working with mana whenua. In contrast to the RMA, decisions relating to plan-making and development, including the approval or rejection of submissions, will be made by the planning committee for the region rather than solely by local authorities.

181. The Panel considered that this approach would create better outcomes for the environment and shift away from plans that lock in land and resource management approaches, protecting the status quo – and would create plans that better respond to environmental pressures and address environmental or social issues, such as housing supply.

182. Clause 20 states that the purpose of an NBA plan is to further the purpose of the Act by providing a framework for the integrated management of a region’s environment.

183. Clause 21 provides for how NBA plans must be prepared. A planning committee is responsible for preparing the NBA plan in each region, following a specified process, which is not included in the exposure draft. Clause 21 refers to Schedule 2, Preparation of natural and built environments plans, which is a placeholder for the planning process.

184. Planning committees will have responsibility for preparing and changing plans in their regions. More detail on the nature and makeup of planning committees is included in Schedule 3, including the role of constituent local authorities. The process should provide for the evaluation of policy direction and content, and include pre-notification participation and consultation with relevant parties.

185. Effective public participation can be achieved by undertaking engagement early in the process, and seeking a diverse range of views and targeting different communities of interest. Improved tools, including greater use of digital platforms, could enable a greater reach so everyone has access to the process.

186. The status of plans as secondary legislation (and the applicable requirements under the Legislation Act 2019 and/or the Local Government Act 2002) has not yet been determined, but will be once final decisions have been made relating to responsibility for plan-making.

187. Clause 22 sets out the content that NBA plans must contain, and the manner in which plans will provide for that content.

188. Clause 22(1) states that a plan must include provide for the matters specified in its sub-clauses.

189. This sub-clause requires that a plan state the environmental limits that apply in the region, whether set by the NPF, or by a planning committee under clause 25.

190. NBA plans will play an important role in ensuring that the environment is managed within the environmental limits prescribed under clause 7.

191. This sub-clause requires that a plan must give effect to the NPF in the region as the NPF directs.

192. The NPF will provide NBA plans with a foundation for achieving integrated management in a way that is both consistent nationally and recognises regional differences.

193. Note that clause 24(4) below specifies that the planning committee must assume that the NPF furthers the purpose of the Act, and need not independently make that assessment when giving effect to the NPF. This is consistent with the approach in the King Salmon decision. (King Salmon (SC), above note 7 [Courts of New Zealand website]).

194. This sub-clause requires a plan to promote the environmental outcomes specified in clause 8 subject to any direction given in the NPF.

195. The ‘subject to’ requirement is also consistent with the King Salmon decision.

196. This sub-clause proposes that a plan be consistent with the RSS. The intention is that key strategic decisions made through the RSS are not to be revisited when preparing a plan.

197. This sub-clause requires a plan to identify and provide for matters that are significant to a region, and for the districts within the region.

198. Each region will have different priorities for its natural and built environments. For example, in some regions the development of certain infrastructure may be a priority.

199. Some significant matters will be the same across the region, but geographical spread, various economic and social circumstances, and different communities may mean there are matters that may only be significant to one district within a region.

200. This is currently a placeholder sub-clause, however the intention of this clause is to signal that plans will still need to regulate the topics that are currently described as local authority functions under the RMA (ie both land use and resource allocation functions will need to be translated and described as plan content to ensure that the environment is managed in an integrated way).

201. This sub-clause requires a plan to help resolve conflicts relating to the environment in the region, including any potential conflicts between environmental outcomes described in clause 8. The plan should give plan users more certainty, leaving fewer matters to resolve at the permissions and approval stage, compared to the RMA.

202. However, it is impossible for policies and rules in plans to predict every possible scenario around resource use, so permissions and approvals will still be required in the new system. Plans will set up the regulatory framework for granting these if needed.

203. Because clause 22(1) may not provide a complete list of the matters a plan should contain, additional contents may be added in the full Bill.

204. This sub-clause states that a plan may include anything else that is necessary for the plan to achieve its purpose.

205. Clause 22(2) states that a plan may:

206. Clause 23 states that a planning committee must be appointed for each region:

207. The exposure draft has adopted the Panel’s proposal to develop one plan per region, prepared by a planning committee. The key functions for a planning committee are to make and maintain a plan, approve or reject submissions from an IHP and set environmental limits, where authorised by the NPF.

208. Policy is still in progress on the matters covered by clause 23, and it is expected that a planning committee will have additional functions in the full Bill.

209. Schedule 3 (referred to in clause 23 of the Bill) outlines the membership and support that will be required for a planning committee, and contains placeholders for matters that still require policy development. Clauses 1 to 4 of the Schedule deal with Membership, and clauses 5 to 6 with Support.

210. The Panel recommended that a committee be made up of the local authorities and mana whenua of a region and a representative of the Minister of Conservation. (This is to reflect that Minister’s role with regard to the coastal marine area under the RMA. However, the Minister’s role in the planning committee is not limited to matters within the coastal marine area).

211. The Panel’s approach included a secretariat function to provide advice and administrative support to the planning committee and assist it in carrying out its functions under the NBA.

212. While the exposure draft adopts the Panel’s proposal for planning committees, there are matters still under consideration, including options around the:

213. Clause 24 sets out the matters that the planning committee must have regard to when making decision on an NBA plan, including:

214. Additionally, the committee must apply the precautionary approach. Clause 24(4) states that the committee is entitled to assume that the NPF furthers the purpose of the NBA, and must not independently make that assessment when giving effect to the NPF.

215. The intention of this clause is to ensure that a planning committee appropriately considers the effects that the proposed plan will have on the environment. This would include whether unintended cumulative effects could be created.

216. Clause 24(4) codifies aspects of the Supreme Court’s King Salmon decision, particularly relating to the hierarchy between planning documents. Specifically, by ‘giving effect’ to the NPF, a planning committee is necessarily furthering the purpose of the Act, as this is a requirement of the preparation of the NPF. The implication of this is that when a planning committee implements the NPF into its plan, it must not refer back to the purpose of the Act to interpret how the NPF is to be provided for in the plan.

217. NBA plans will be an important mechanism to reflect te ao Māori perspectives on the environment and manage resources in a way that actively protects iwi, hapū and Māori interests. They are also a key mechanism for giving effect to the principles of Te Tiriti.

218. Clause 24 is not a complete list of the matters that a plan decision-maker will need to consider. It is anticipated that additional matters will be required as the development of the full Bill progresses.

219. Clause 25 provides the planning committee with the power to set an environmental limit for the region in the plan where directed by the NPF, and following the process set out in the NPF.

220. Environmental limits will be set in the NPF, but in some instances it may be desirable for environmental limits be set by planning committees in NBA plans to account for local variation, especially between ecosystems.

221. It is expected that additional provisions specifying how a planning committee undertakes this function will be provided in the full Bill.

222. A comprehensive outline of the plan-making process is not included in the exposure draft including:

223. Matters not included in the exposure draft in relation to plan governance and decision-making include:

PART A: Explanatory material to the exposure draft of the Natural and Built Environments Bill

June 2021

© Ministry for the Environment