C.1 The overall approach

The principle of using guideline values is simple: we measure the level of ‘faecal indicator organisms’, which do not necessarily cause disease themselves but signal the potential presence of disease-causing organisms. Guideline values of faecal indicator organisms such as enterococci have been used successfully for a long time in recreational waters. However, there are still questions about the effectiveness of this approach for monitoring and measuring water quality, and a number of environmental and physical factors may influence the usefulness of faecal bacteria as indicators.

The main constraints to the approach used in current guidelines are as follows:

- Management actions are retrospective – they can be deployed only after human exposure to the hazard.

- While beaches may be designated as suitable or unsuitable for recreational activities, there is in fact a gradient of increasing severity, variety and frequency of health effects with increasing sewage pollution. It is therefore desirable to promote incremental improvements or prevention, prioritising ‘worst features’, to achieve cost-effective intervention.

- Although enterococci have been identified as having the best relationship with health effects in marine waters, they may also be derived from other than faecal sources in some conditions.

- Such conditions as sub-tropical temperatures and the influence of mangrove swamps and freshwater run-off from dense vegetation have been identified in parts of New Zealand.

- Many New Zealand recreational sites are at estuaries, where historical results from both Escherichia coli (E. coli) (as the preferred indicator for freshwater faecal contamination) and enterococci are required for an assessment of health risk.

Such constraints to the use of guideline values are not confined to New Zealand. In November 1998 a group of experts from the WHO, the Commission of the European Communities and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) met in Annapolis, USA, to consider ways to address such anomalies and constraints. The experts agreed that an improved approach to regulating recreational water that better reflected health risk and provided enhanced scope for effective management intervention was necessary – and feasible. The resulting approach has become known as the ‘Annapolis Protocol’. Published in 1999, it covers approaches involving both an environmental hazard assessment and a microbiological water quality assessment.

See Note G(x) for further details on the Annapolis Protocol.

The Ministry for the Environment responded by establishing the Marine Bathing Working Group in 1999 as a consultation of interested parties to investigate the application of an ‘Annapolis’ approach to New Zealand conditions. The approach has been modified after consultation and trial during the 2001 bathing season. It has also been modified to incorporate updates from the WHO contained in their publications Bathing Water Quality and Human Health: Protection of the human environment water, sanitation and health (WHO 2001) and Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments: Volume 1 Coastal and Freshwaters (WHO 2003), and as such is incorporated as part of these guidelines.

This approach has also been applied in the development of the freshwater guidelines, for which the Ministry for the Environment established the Freshwater Guidelines Advisory Group. The freshwater guidelines were trialled over the 2003 bathing season, and have been updated in light of feedback.

C.2 The framework

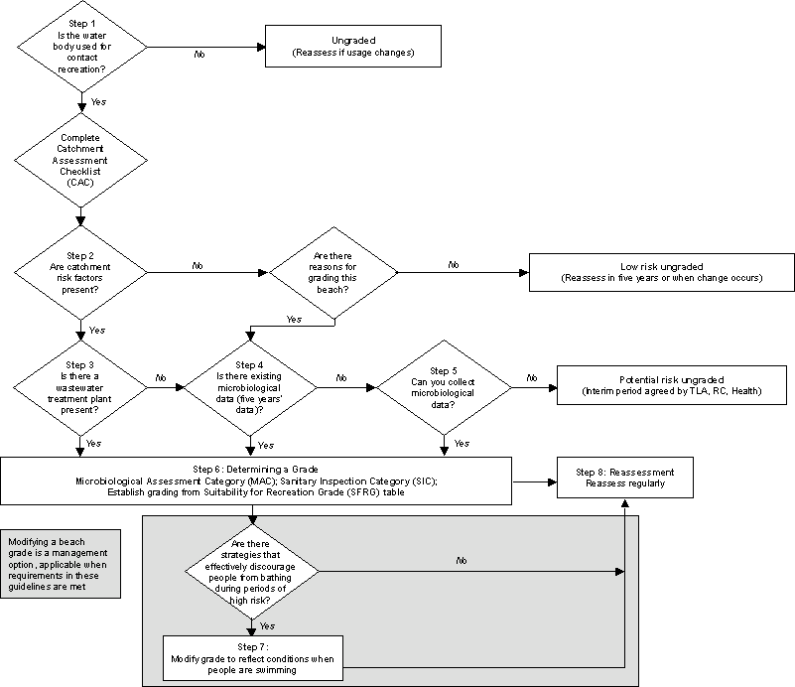

The framework used in these guidelines is a combination of catchment risk grading and single samples to assess suitability for recreation. This is a move away from the sole use of quantitative ‘guideline’ values of faecal indicator bacteria towards a qualitative ranking of faecal loading in a recreational water environment, supported by direct measurement of appropriate faecal indicators. The framework is summarised in Figure C1.

Figure C1: Surveillance requirements for graded beaches

Image: Data source — Modified from WHO, 2003.

Image: Data source — Modified from WHO, 2003.

An explanation of all the features of this framework, including the Catchment Assessment Checklist (used to derive the Sanitary Inspection Category), the Microbiological Assessment Category and the Sanitary Inspection Category, will be given when we look in Part II at setting out to grade a beach. For the moment we are focusing on the final result of this process – the Suitability for Recreation Beach Grade.

This grade provides an indication of the general condition of a beach. The risk of becoming sick from swimming at a beach increases as the beach grading shifts from Very Good to Very Poor.

Conditions affecting water quality vary for the middle range of beach grades (Good, Fair and Poor). For example, ‘Good’ beaches usually comply with the guidelines, but events such as high rainfall increase the risk of contamination levels from run-off.

Weekly monitoring should be carried out during the bathing season for these middle-range beaches. For beaches where routine monitoring will be ongoing during the bathing season, the three-tier system applies, analogous to traffic lights:

- Highly likely to be uncontaminated (green): ‘suitable’ for bathing, but requiring water managers to continue surveillance (e.g. routine monitoring)

- Potentially contaminated (amber): ‘potentially unsuitable’, requiring water managers to undertake further investigation to assess the suitability for recreation

- Highly likely to be contaminated (red): ‘highly likely to be unsuitable’, requiring urgent action from water managers, such as public warnings.

The public will be informed when swimming is not recommended: for the marine guidelines, when two consecutive samples taken from the beach exceed the action level of the microbiological water-quality guidelines; and for freshwater, when one sample exceeds the action level.

See Note H(i) for information on sampling times and periods.

The grading process identifies sources of faecal contamination, such as sewer overflows caused by heavy rainfall, which influence the final Suitability for Recreation Grade. Contamination events may be triggered by specific conditions (e.g. rainfall). Where monitoring agencies can predict such contamination events, they may initiate management interventions to deter use of the site. Where these interventions can be demonstrated to be effective in discouraging use of the recreational site, the initial grade may be modified to reflect the usual water-quality conditions at that site. This is achieved by removing the source of the predictable exceedance events from the catchment assessment.

See Note H(xii) for more information on modifying beach grades.

We will now go on to look at putting this monitoring, grading and public warning system into practice.

Such modification of a grade, achieved by management practices, reflects the quality of water at the time of use. It does not alter the environmental conditions and microbiological data governing the initial grading.

The framework in these guidelines uses both beach grading and guideline values. Beach grades provide the basic means to assess suitability for recreation over time, using a combination of knowledge of beach catchment characteristics and microbiological information gathered over previous years. Single sample results are compared against guideline values, to help water managers determine when management intervention is required. The guideline values that have been decided on are summarised in D.5.

D.1 Designation of a contact recreation area

People are generally free to swim wherever they like around New Zealand’s many beaches, but it would be impossible to monitor them all. Criteria for identifying which beaches to monitor will vary from region to region, but will generally be based on usage, available information and the resources available to the monitoring authority. The Ministry for the Environment and Ministry of Health recommend that the beaches to be included in the monitoring programme be agreed by all agencies involved in the programme and documented in the regional protocol.

D.2 Sampling beach water

The following information is provided to help develop a sampling programme for monitoring beaches.

Sampling period

Samples should be collected during the bathing season, or when the water body is used for contact recreation. The bathing season will vary according to location, but will generally extend from 1 November to 31 March. Sampling should take place between 8 am and 6 pm.

See Note H(i) for details on sampling times and periods.

Bacteriological indicators, catchment assessment and single samples

For marine water the preferred indicator is enterococci. The New Zealand Marine Bathing Study showed that enterococci are the indicator most closely correlated with health effects in New Zealand marine waters, confirming a pattern seen in a number of overseas studies (as reviewed by Prüss 1998). Faecal coliforms and E. coli were not as well correlated with health risks, although they may be used as an indicator in addition to enterococci in environmental conditions where enterococci levels alone may be misleading. Estuarine and brackish waters may require a combination of both indicators, identified through the catchment assessment.

E. coli rather than enterococci should be used as an indicator wherever the primary source of faecal contamination is a waste stabilisation pond (WSP). Enterococci are damaged in WSPs (Davies-Colley et al 1999), whereas faecal coliforms that emerge from a pond appear to be more sunlight resistant than those that enter it (Sinton et al 1999). Thus WSP enterococci are inactivated in receiving water faster than WSP faecal coliforms (Sinton et al 2002).

See Appendix 2 for a detailed report on the development of indicators internationally.

Type of sampling programme

The guidelines recommend a systematic random-sampling regime. Generally this means samples should be collected weekly, regardless of the weather. There may be exceptions if conditions present a health and safety hazard, in which case samples should be collected as soon after the programmed time as possible.

Type of sampling programme

Samples should be collected at approximately 15 cm below the surface at a point where the depth of the water is approximately 0.5 metres (based on data in McBride, Salmond, et al 1998).

See Note H(ii) for techniques for taking and analysing samples.

D.3 Grading a beach

The results obtained from weekly sampling under a monitoring programme are only one aspect of the process. We also need to grade the beach we are monitoring. There are two components to grading beaches:

- the Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC), which generates a measure of the susceptibility of a water body to faecal contamination

- historical microbiological results, which generate a Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC). This provides a measurement of the actual water quality over time.

The two combined give an overall Suitability for Recreation Grade (SFRG), which describes the general condition of a site at any given time, based on both risk and indicator bacteria counts. The SIC, MAC and SFRG are explained below.

Note: Whereas before the guidelines were not applicable where a beach received treated sewage, the grading system now allows an assessment of the health risk present at a beach (via the Sanitary Inspection Category) after evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment processes.

Assessing a beach for the first time

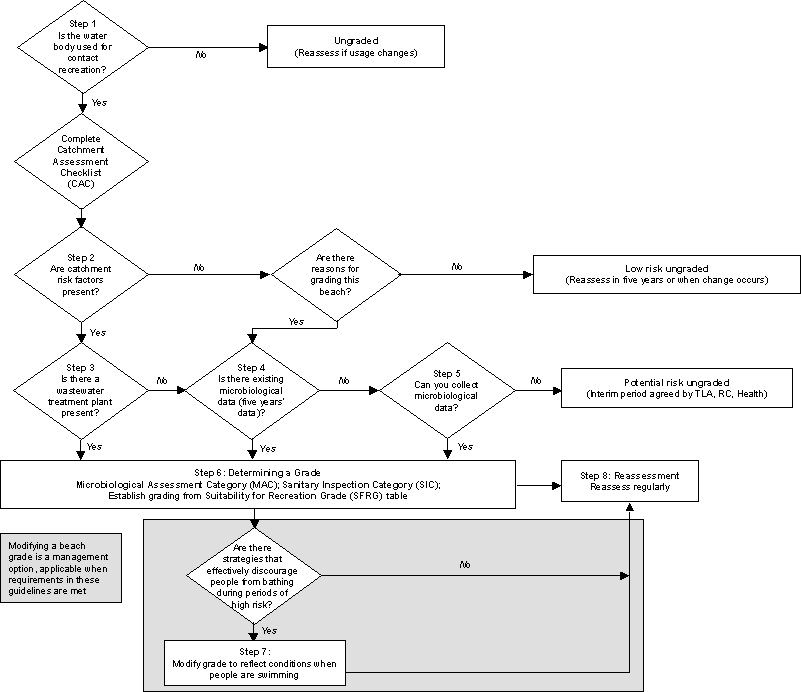

The recreational water-quality decision tree (Figure D1) outlines the process that will lead to grading a beach. All beaches will have to go through this process, which helps to identify the information needed in order to grade a site.

Collecting background information

As much information as is feasible about the site should be collected to make the assessment of risk-contributing factors as accurate as possible. Sources of information will vary from region to region. Gathering this information may involve a range of agencies (health, water and sewerage industries; district, city, regional councils), which will have access to different information for the same beach catchment. Relevant information includes drainage plans, site maps, previous season’s monitoring results, and consent applications.

The purpose of the decision tree is to provide a logical course that allows the responsible authority to make defensible decisions on whether or not to grade a particular water body.

Figure D1: Recreational water-quality decision tree

The following notes describe the process and decisions required to complete each of the steps described in Figure D1.

Step 1: Is the water body used for contact recreation?

Beaches are considered either contact recreation areas (well used) or not contact recreation areas (not well used). The guidelines apply to contact recreation areas, and involve grading and monitoring.

This does not mean water quality can be allowed to deteriorate at ungraded beaches. Rather, it is expected that the guidelines will be rigorously applied at graded beaches, while the monitoring required and associated costs may not be justified at ungraded beaches.

Which beaches are monitored will be a local decision, and should be decided on a site-specific basis by the local authorities (regional or local authority, or Medical Officer of Health) depending on the local relevance of the site.

Step 2: Are catchment risk factors present?

The ‘risk factors’ refer to activities in the catchment that may result in faecal contamination of a recreational water site. To assess the catchment risk factors, the Catchment Assessment Checklist should be completed.

See Note H(iv) for the Catchment Assessment Checklist for marine recreational waters.

‘Yes’ responses to the ‘Microbiological Hazards’ (Part D) section of the checklist show the presence of catchment risk factors that affect, or are likely to affect, recreational water quality.

Step 3: Is there a wastewater treatment plant present?

Wastewater treatment processes often effectively reduce microbial indicators such as enterococci but are less effective at removing pathogens such as viruses. The result may be an altered pathogen-to-indicator ratio compared to that of untreated waste. This means that if there is a wastewater treatment plant present, pathogens may still be present even when indicator levels are very low.

A ‘Yes’ answer in this box means the wastewater treatment plant discharges directly to the recreational water, or to an area where discharge water may reasonably be expected to be carried to a recreational water site by tides, currents or streams.

Step 4: Is there existing microbiological data?

Ideally there should be 100 data points [Data points are the results of samples collected.] or greater collected over the previous five years, although it is feasible to consider grading with a minimum of 20 data points collected over one full bathing season. The data should normally be on enterococci. The grading should be considered as interim until five years of data have been collected.

Note: Follow-up samples from an alert or action mode response should not be included in the data used to generate an MAC (see Step 6). If using the software provided by the Ministry for the Environment to generate grades, follow-up samples should be manually removed from the dataset.

See Note H(xv) for details on the software available to analyse results.

Step 5: Can you collect microbiological data?

If microbiological data is required, the sampling programme should collect at least 20 data points over the period of greatest recreational use. This will normally be the summer bathing season, but may vary with the types of recreational activity most common in the area.

Step 6: Determining a grade

In order to grade a recreational water body, the authority must establish:

- the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC): an MAC category (ranging from A to D) is established from the existing or collected microbiological data; definitions for the different categories are given in Table D1.

- the Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC): this category is either Very High, High, Moderate, Low or Very Low, and is determined for a specific water body by using the SIC flow chart.

See Note H(iv) for the Sanitary Inspection Category flow chart for marine waters.

The information for using the flow chart should come from the Catchment Assessment Checklist (CAC), Part D, and may require further investigation to establish the principal source of contamination.

Determining a grade involves using both the MAC and the SIC (see Table D2). A grade is established on the basis of five years’ data. Thereafter recalculation of the grade may be done annually using the previous five years’ data.

Step 7: Modifying a grade

Modifying a beach grade is a management option, applicable when requirements in these guidelines have been met.

Beach grades may be modified where management interventions can be demonstrated to effectively discourage recreational use during occasional and predictable contamination events. The modified grade should reflect the water – quality conditions the public are usually exposed to, and be verified by the Medical Officer of Health.

See Note H(xii) for more information on modifying beach grades.

Step 8: Reassessment

Reassess on a five-yearly basis, or sooner if significant change occurs. Such changes will be reflected in new information in parts A, B, C and D of the Catchment Assessment Checklist. Examples of significant change would be:

- altered catchment characteristics or land use

- significantly higher or lower microbiological indicator levels

- major infrastructure works affecting water-quality parameters.

Beaches graded Very Good will almost always comply with the guideline values for recreation, and there are few sources of faecal contamination in the catchment. Consequently there is a low risk of illness from bathing. Beaches graded Very Poor are in catchments with significant sources of faecal contamination, and they rarely pass the guidelines. The risk of illness from bathing at these beaches is high, and swimming is not recommended. For the remaining beaches (Good, Fair and Poor) it is recommended that weekly monitoring be carried out during the bathing season. The public will be informed when guideline values are exceeded and swimming is not recommended.

The following table lists the criteria that define the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC), based on five years’ historical data.

Table D1: Microbiological Assessment Category definitions for marine waters

| A | Sample 95 percentile =<40 enterococci/100mL |

| B | Sample 95 percentile <41-200 enterococci/100mL |

| C | Sample 95 percentile <201-500 enterococci/100mL |

| D | Sample 95 percentile >500 enterococci/100mL |

Source: WHO 2001.

Note: The Hazen method is used for calculating the 95 percentiles (It is important to note there are several ways to calculate percentiles. Each uses a different formula, generating different results. The Hazen method has been chosen for these guidelines, as it tends to be about the ‘middle’ of all the options.).

The Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC)

The SIC allows the principal microbiological contamination from faecal sources to be identified and assigns a category according to risk. This category is then combined with the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC) to determine a Suitability for Recreation Grade for each site in the programme.

Sources of human faecal contamination identified by the SIC may, as a result of treatment, be considered of low public health risk. There may, however, still be cultural or aesthetic objections to such faecal contamination.

This category is either Very High, High, Moderate, Low or Very Low, and is found for a specific water body by use of the SIC flow chart. The information for using the flow chart should come from Part D of the Catchment Assessment Checklist (CAC) and may require further investigation to establish the principal source of contamination.

See Note H(iii) for details on how to establish a Sanitary Inspection Category.

Suitability for Recreation Grade (SFRG)

SFRGs are Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor, and Very Poor. To find the appropriate grading for the recreational water body, locate the box in the Suitability for Recreation Grade in Table D2 that coincides with both the MAC and SIC for the water body.

Table D2: Suitability for Recreation Grade Matrix

| Susceptibility to faecal influence | Microbiological Assessment Category Indicator counts (as percentiles - see Table D1) |

Exceptional circumstances *** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A =< 40 enterococci/ 100 mL |

B 41-200 enterococci/ 100 mL |

C 20-500 enterococci/ 100 mL |

D >500 enterococci/ 100 mL |

||

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Very Low | Very Good | Very Good | Follow Up** | Follow Up** | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Low | Very Good | Good | Fair | Follow Up** | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Moderate | Follow Up* | Good | Fair | Poor | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: High | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Poor | Very Poor | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Very High | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Very Poor | |

| Exceptional circumstances | |||||

Notes:

- * Indicates unexpected results requiring investigation (reassess SIC and MAC). If after reassessment the SFRG is still ‘follow up’, then assign a conservative grade (i.e. the first grade to the right of the ‘follow up’ in the same SIC row). This follows the precautionary principle applied in public health.

- ** Implies non-sewage sources of indicators, and this should be verified. If after verification the SFRG is still ‘follow up’, then assign a conservative grade (i.e. the first grade after ‘follow up’ in the same MAC column).

- *** Exceptional circumstances: relate to known periods of higher risk for a graded beach, such as during a sewer rupture or an outbreak of a potentially waterborne pathogen in the community of the recreational area catchment. Under such circumstances a grading would not apply until the episode has abated.

(For example: if MAC = C and SIC = Moderate, then Suitability for Recreation Grade = Fair.)

See Note H(xiii) for percentile guideline values for seawater.

See Note H(xv) for information on software to use for grading beaches.

D.4 Monitored beaches: surveillance, alert and action modes

So far we have looked at deciding which beaches to grade, and how to monitor a beach by taking samples. Next we need to look at putting these together in a process to manage the different scenarios that may arise.

These guidelines propose a three-tier management framework based on bacteriological indicator values:

- surveillance – involves routine (e.g. weekly) sampling of bacteriological levels

- alert – requires investigation of the causes of the elevated levels and increased sampling to enable the risks to bathers to be more accurately assessed

- action – requires the local authority and health authorities to warn the public that the beach is considered unsuitable for recreation.

Surveillance (routine monitoring)

Under the surveillance condition, beaches graded Good, Fair or Poor have the potential to be affected by faecal contamination events, and routine monitoring (e.g. weekly sampling) must continue (see Box 1). Guidance on when and where to sample can be found in section D.2, with further information in Note H(i).

Alert (amber) mode: single samples

The alert mode is triggered when a single bacteriological sample exceeds a predetermined value. Under alert mode, sampling frequency should be increased to daily, and catchment assessment data referred to for potential faecal sources. A sanitary survey should then be undertaken to positively identify the sources of contamination and the potential management options.

See Note H(iv) for the Sanitary Inspection Category flow chart for marine recreational waters.

Action (red) mode: consecutive samples

The action mode is triggered when two consecutive single samples (within 24 hours) exceed a pre-determined value (see Box 1 for guideline values). Under the action mode, the local authority and health authorities warn the public, using appropriate methods, that the beach is unsuitable for recreation and arrange for the local authority to erect signs at the beach warning the public of a health danger.

See Note H(xvi) for information on reporting to the public.

See Note H(xvii) for management responses to exceedances.

D.5 Marine bathing guideline values (graded beaches)

The marine bathing guidelines are summarised in Box 1 . They are based on keeping illness risks associated with recreational water use to less than about 2%.

See Appendix 2 for details on how guideline values have been developed.

Box 1: Surveillance, alert and action levels for marine waters

Surveillance/Green Mode: No single sample greater than 140 enterococci/100 mL.

- Continue routine (e.g. weekly) monitoring.

Alert/Amber Mode: Single sample greater than 140 enterococci/100 mL.

- Increase sampling to daily (initial samples will be used to confirm if a problem exists).

- Consult the CAC to assist in identifying possible sources.

- Undertake a sanitary survey, and identify sources of contamination.

Action/Red Mode: Two consecutive single samples (resample within 24 hours of receiving the first sample results, or as soon as is practicable) greater than 280 enterococci/100 mL.

- Increase sampling to daily (initial samples will be used to confirm if a problem exists).

- Consult the CAC to assist in identifying possible sources.

- Undertake a sanitary survey, and identify sources of contamination.

- Erect warning signs.

- Inform public through the media that a public health problem exists.

Notes: Either of the following methods may be used to enumerate enterococci: Enterolert™ or EPA Method 1600.* For national consistency it is recommended that accredited laboratories be used for microbiological tests (e.g. IANZ accreditation). Samples to test compliance should be over the bathing season appropriate to that locality (at least 1 November to 31 March) and sampling times should be restricted to between 0800 hours and 1800 hours.

*USEPA National Centre for Environmental Publications and Information (NCEPI), 11029 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH45242, USA.

D.6 Conditions of using the guidelines

- These guidelines must not be used as a measure of suitability for recreation when there is a major outbreak of a potentially waterborne disease in the community, and that community’s sewage contributes to the microbiological contamination to the water. Such conditions constitute ‘exceptional circumstances’. The guidelines do not apply then because the relationship between indicator organisms and disease was derived when there were no known outbreaks of waterborne diseases in the community. When there is such an outbreak, health risks may be increased because of a higher-than-usual ratio of pathogen concentration to indicators in the water.

- Implementing the guidelines emphasises the need and importance for traditional sanitary surveys, i.e. a catchment assessment.

- Compliance with the guidelines generally indicates that a beach is suitable for recreation. There are exceptions however. For example, effluent may be treated to a level where the indicator bacterial levels are very low, but other pathogens such as viruses or protozoa may still be present at high levels. The assessment of such conditions should be considered during the procedure for grading a beach.

- It is important that water managers use these guidelines judiciously, and carefully consider where they can be applied.

These guidelines are not intended to be used as the basis for establishing conditions for discharge consents, although they may be used as a component for decision making.

See the introduction of these guidelines for discussion on what this document covers.

The framework in these guidelines uses both beach grading and guideline values. Beach grades provide the basic means to assess suitability for recreation over time, using a combination of knowledge of beach catchment characteristics and microbiological information gathered over previous years. Single-sample results are compared against guideline values, to help water managers determine when management intervention is required. The guideline values that have been decided on are summarised in E.5.

E.1 Designation of a contact recreation area

People are generally free to swim wherever they like around New Zealand’s many beaches, but it would be impossible to monitor them all. Criteria for identifying which beaches to monitor will vary from region to region, but will generally be based on usage, available information and the resources available to the monitoring authority. The Ministry for the Environment and Ministry of Health recommend that the beaches to be included in the monitoring programme be agreed by all agencies involved in the programme and documented in the regional protocol.

E.2 Sampling rivers and lakes

The following information is provided to help develop a sampling programme for monitoring rivers and beaches.

Sampling period

Samples should be collected during the bathing season, or when the water body is used for contact recreation. For rivers this may exclude periods of high flow, during which hazardous river conditions would prohibit bathing. The bathing season will vary according to location, but will generally extend from 1 November to 31 March. Sampling should take place between 8 am and 6 pm.

See Note H(i) for details on sampling times and periods.

Bacteriological indicators, catchment assessment and single samples

The pathogens occurring in contaminated freshwater are the same as those occurring in marine waters, except that survival times in freshwater are likely to be longer, especially for protozoan cysts (e.g. Giardia and Cryptosporidium) and viruses. E. coli is the preferred indicator organism for freshwaters, although there may be exceptions (e.g. in proximity to large waste stabilisation pond outfalls). Enterococci should not be used because some enterococci can multiply from natural sources, such as the decay of leaf material. This means that enterococci levels can be very high even in pristine waters, but this may not necessarily indicate high levels of pathogens.

Type of sampling programme

The guidelines recommend a systematic random-sampling regime. Generally this means samples should be collected weekly, regardless of the weather. There may be exceptions if conditions present a health and safety hazard, in which case samples should be collected as soon after the programmed time as possible.

Sampling depth

Samples should be taken at approximately 30 cm below the surface, where the depth of the water is approximately 1 metre.

See note H(ii) for techniques for taking and analysing samples.

E.3 Grading a freshwater site

The results we obtain from microbiological sampling under a monitoring programme are only one aspect of the process. We also need to grade the site we are monitoring. There are two components to grading freshwater sites:

- the Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC), which generates a measure of the susceptibility of a water body to faecal contamination

- historical microbiological results, which generate a Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC). This provides a measurement of the actual water quality over time.

The two combined give an overall Suitability for Recreation Grade (SFRG), which describes the general condition of a site at any given time, based on both risk and indicator bacteria counts. The SIC, MAC and SFRG are explained below.

Note: Whereas before the guidelines were not applicable where a site received treated sewage, the grading system now allows an assessment of the health risk present at a site after evaluating the effectiveness of the treatment processes.

Assessing a freshwater site

The recreational water-quality decision tree (Figure E1) and accompanying descriptions outline the process that will lead to grading a site. All freshwater sites will have to go through this process, which helps to identify the information needed in order to grade a site.

Collecting background information

As much information as is feasible about the site should be collected to make the assessment of risk-contributing factors as accurate as possible. Sources of information will vary from region to region. Gathering this information may involve a range of agencies (health, water and sewerage industries; district, city, regional councils), which will have access to different information for the same site catchment. Relevant information includes drainage plans, site maps, previous season’s monitoring results, and consent applications. The purpose of the decision tree is to provide a logical course that allows the responsible authority to make defensible decisions on whether or not to grade a particular water body.

Figure E1: Recreational water-quality decision tree (duplicated)

The following notes describe the process and decisions required to complete each of the steps described in Figure E1.

Step 1: Is the water body used for contact recreation?

Beaches are considered either contact recreation areas (well used) or not contact recreation areas (not well used). The guidelines apply to contact recreation areas, and involve grading and monitoring.

This does not mean water quality can be allowed to deteriorate at ungraded beaches. Rather, it is expected that the guidelines will be rigorously applied at graded beaches, while the monitoring required and associated costs may not be justified at ungraded beaches.

Which beaches are monitored will be a local decision, and should be decided on a site-specific basis by the local authorities (regional or local authority, or Medical Officer of Health) depending on the local relevance of the site.

Step 2: Are catchment risk factors present?

The ‘risk factors’ refer to activities in the catchment that may result in faecal contamination of a recreational water site. To assess the catchment risk factors, the Catchment Assessment Checklist should be completed.

See Note H(vii) for the Catchment Assessment Checklist for freshwater recreational areas.

‘Yes’ responses to the ‘Microbiological Hazards’ (Part D) section of the checklist show the presence of catchment risk factors that affect, or are likely to affect, recreational water quality.

Step 3: Is there a wastewater treatment plant present?

Wastewater treatment processes often effectively reduce microbial indicators such as enterococci but are less effective at removing pathogens such as viruses. The result may be an altered pathogen-to-indicator ratio compared to that of untreated waste. This means that if there is a wastewater treatment plant present, pathogens may still be present even when indicator levels are very low.

A ‘Yes’ answer in this box means the wastewater treatment plant discharges directly to the recreational water, or to an area where discharge water may reasonably be expected to be carried to a recreational water site by tides, currents or streams.

Step 4: Is there existing microbiological data?

Ideally there should be 100 data points [Data points are the results of samples collected.] or greater collected over the previous five years, although it is feasible to consider grading with a minimum of 20 data points collected over one full bathing season. The data should normally be E. coli. The grading should be considered as interim until five years of data have been collected.

Note: Follow-up samples from an alert or action mode response should not be included in the data used to generate an MAC (see Step 6). If using the software provided by the Ministry for the Environment to generate grades, follow-up samples should be manually removed from the dataset.

See Note H(xv) for information on the software available to analyse results.

Step 5: Can you collect microbiological data?

If microbiological data is required, the sampling programme should collect at least 20 data points over the period of greatest recreational use. This will normally be the summer bathing season, but may vary with the types of recreational activity most common in the area.

Step 6: Determining a grade

In order to grade a recreational water body, the authority must establish:

- the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC): an MAC category (ranging from A to D) is established from the existing or collected microbiological data; definitions for the different categories are given in Table E1.

- the Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC): this category is either Very High, High, Moderate, Low or Very Low, and is determined for a specific water body by using the SIC flow chart.

See Note H(vii) for the Sanitary Inspection Category flow charts for rivers and lakes.

The information for using the flow chart should come from the Catchment Assessment Checklist (CAC), Part D, and may require further investigation to establish the principal source of contamination.

Determining a grade involves using both the MAC and the SIC (see Table E2: Suitability for Recreation Grade matrix). A grade is established on the basis of five years’ data. Thereafter recalculation of the grade may be done annually using the previous five years’ data.

Step 7: Modifying a grade

Modifying a beach grade is a management option, applicable when requirements in these guidelines have been met.

Beach grades may be modified where management interventions can be demonstrated to effectively discourage recreational use during occasional and predictable contamination events. The modified grade should reflect the water quality conditions the public are usually exposed to, and be verified by the Medical Officer of Health.

See Note H(xii) for more information on modifying beach grades.

Step 8: Reassessment

Reassess on a five-yearly basis, or sooner if significant change occurs. Such changes will be reflected in new information in parts A, B, C and D of the Catchment Assessment Checklist. Examples of significant change would be:

- altered catchment characteristics or land use

- significantly higher or lower microbiological indicator levels

- major infrastructure works affecting water-quality parameters.

Beaches graded Very Good will almost always comply with the guideline values for recreation, and there are few sources of faecal contamination in the catchment. Consequently there is a low risk of illness from bathing. Beaches graded Very Poor are in catchments with significant sources of faecal contamination, and they rarely pass the guidelines. The risk of illness from bathing at these beaches is high, and swimming is not recommended. For the remaining beaches (Good, Fair and Poor) it is recommended that weekly monitoring be carried out during the bathing season. The public will be informed when guideline values are exceeded and swimming is not recommended.

The Microbiological Assessment Category

The following table lists the criteria that define the MAC, based on five years’ historical data.

Table E1: Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC) definitions

| A | Sample 95 percentile =<130 Escherichia coli per 100 mL |

| B | Sample 95 percentile 131–260 Escherichia coli per 100 mL |

| C | Sample 95 percentile 261–550 Escherichia coli per 100 mL |

| D | Sample 95 percentile >550 Escherichia coli per 100 mL |

Note: The Hazen method is used for calculating the 95 percentiles (It is important to note there are several ways to calculate percentiles. Each uses a different formula, generating different results. The Hazen method has been chosen for these guidelines, as it tends to be about the ‘middle’ of all the options.).

The Sanitary Inspection Category (SIC)

The SIC allows the principal microbiological contamination from faecal sources to be identified and assigns a category according to risk. This category is then combined with the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC) to determine a Suitability for Recreation Grade for each site in the programme.

Sources of human faecal contamination identified by the SIC may, as a result of treatment, be considered of low public health risk. There may, however, still be cultural or aesthetic objections to such faecal contamination.

This category is either Very High, High, Moderate, Low or Very Low, and is found for a specific water body by use of the SIC flow chart. The information for using the flow chart should come from Part D of the Catchment Assessment Checklist (CAC) and may require further investigation to establish the principal source of contamination.

See Note H(iii) for detail on how to establish a Sanitary Inspection Category.

The Suitability for Recreation Grade

SFRGs are Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor and Very Poor. To find the appropriate grading for the recreational water body, locate the box in the Suitability for Recreation Grade table (Table E2) that coincides with both the MAC and SIC for the water body.

Table E2: Suitability for Recreation Grade for freshwater sites

| Susceptibility to faecal influence | Microbiological Assessment CategoryIndicator counts (as percentiles – refer Table E1) |

Exceptional circumstances *** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A =< 130 E. coli/ 100 mL |

B 131–260 E. coli/ 100 mL |

C 261–550 E. coli/ 100 mL |

D >550 E. coli/ 100 mL |

||

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Very Low | Very Good | Very Good | Follow Up** | Follow Up** | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Low | Very Good | Good | Fair | Follow Up** | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Moderate | Follow Up* | Good | Fair | Poor | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: High | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Poor | Very Poor | |

| Sanitary Inspection Category: Very High | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Follow Up* | Very Poor | |

| Exceptional circumstances | |||||

Notes:

- * Indicates unexpected results requiring investigation (reassess SIC and MAC).

- ** Implies non-sewage sources of indicators, and this should be verified.

- *** Exceptional circumstances: relate to known periods of higher risk for a graded beach, such as during a sewer rupture or an outbreak of a potentially waterborne pathogen in the community of the recreational area catchment. Under such circumstances a grading would not apply until the episode has abated.

(For example: if MAC = C and SIC = Moderate, then Suitability for Recreation Grade = Fair.)

See Note H(xiii) for percentile guideline values for freshwater.

See Note H(xv) for information on software to use for grading beaches.

E.4 Monitored beaches: surveillance, alert and action modes

So far we have looked at deciding which beaches to grade, and how to monitor a beach by taking samples. Next we need to look at putting these together in a process to manage the different scenarios that may arise.

These guidelines propose a three-tier management framework based on bacteriological indicator values:

- surveillance – involves routine (e.g. weekly) sampling of bacteriological levels

- alert – requires investigation of the causes of the elevated levels and increased sampling to enable the risks to bathers to be more accurately assessed

- action – requires the local authority and health authorities to warn the public that the beach is considered unsuitable for recreation.

Surveillance (routine monitoring)

Under the surveillance condition, beaches graded Good, Fair or Poor have the potential to be affected by faecal contamination events, and routine monitoring (e.g. weekly sampling) must continue (see Box 2). Guidance on when and where to sample can be found in section E.2, with further information in Note H(i).

Alert (amber) mode: single samples

The alert mode is triggered when a single bacteriological sample exceeds a predetermined value. Under alert mode, sampling frequency should be increased to daily, and catchment assessment data referred to for potential faecal sources. A sanitary survey should then be undertaken to positively identify the sources of contamination and the potential management options.

See Note H(vii) for the Sanitary Inspection Category flow charts for rivers and lakes.

Action (red) mode: consecutive samples

The action mode is triggered when a single sample exceeds a pre-determined value (see Box 2 for guideline values). Under the action mode, the local authority and health authorities warn the public, using appropriate methods, that the beach is unsuitable for recreation and arrange for the local authority to erect signs at the beach warning the public of a health danger.

See Note H(i) for discussion on sampling requirements.

See Note H(xvi) for information on reporting to the public.

See Note H(xvii) for management responses to exceedances.

E.5 Freshwater surveillance, alert and action levels

The surveillance, alert and action levels are summarised in Box 2. They are based on an estimate that approximately 5% of Campylobacter infections could be attributable to freshwater contact recreation.

See Appendix 2 for details on how guideline values have been developed.

Box 2: Surveillance, alert and action levels for freshwater

Acceptable/Green Mode: No single sample greater than 260 E. coli/100 mL.

- Continue routine (e.g. weekly) monitoring.

Alert/Amber Mode: Single sample greater than 260 E. coli/100 mL.

- Increase sampling to daily (initial samples will be used to confirm if a problem exists).

- Consult the CAC to assist in identifying possible location of sources of faecal contamination.

- Undertake a sanitary survey, and report on sources of contamination.

Action/Red Mode: Single sample greater than 550 E. coli/100 mL.

- Increase sampling to daily (initial samples will be used to confirm if a problem exists).

- Consult the CAC to assist in identifying possible location of sources of faecal contamination.

- Undertake a sanitary survey, and report on sources of contamination.

- Erect warning signs.

- Inform public through the media that a public health problem exists.

Notes:

- Colilert™ is the method of choice to enumerate E. coli or EPA Method 1103.1, 1985 Membrane Filter Method for E. coli (this method gives a result for E. coli within 24 hours): USEPA ICR Microbial Laboratory Manual.* This method and the MPN Method for E. coli, which is also acceptable (but gives a result in 48 hours), is described in the 20th edition of Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water, American Public Health Association. These methods must be used to enumerate E. coli unless an alternative method is validated to give equivalent results for the waters being tested.

- Samples to test compliance should be over the bathing season appropriate to that locality (at least 1 November to 31 March) and sampling times should be restricted to between 0800 hours and 1800 hours.

* USEPA National Centre for Environmental Publications and Information (NCEPI), 11029 Kenwood Road, Cincinnati, OH 45242, USA (Document No. EPA?821-C-97-004).

E.6 Conditions of using the guidelines

Use of these guidelines is conditional on the following.

- These guidelines must not be used as a measure of suitability for recreation when there is a major outbreak of a potentially waterborne disease in the community, and that community’s sewage contributes to the microbiological contamination of the water. Such conditions constitute ‘exceptional circumstances’. The guidelines do not apply then because the relationship between indicator organisms and disease was derived when there were no known outbreaks of waterborne diseases in the community. When there is such an outbreak, health risks may be increased because of a higher-than-usual ratio of pathogen concentration to indicators in the water.

- Implementing the guidelines emphasises the need and importance for traditional sanitary surveys.

- Compliance with the guidelines generally indicates that a beach is suitable for recreation. There are exceptions however. For example, effluent may be treated to a level where the indicator bacterial levels are very low, but other pathogens such as viruses or protozoa may still be present at high levels. The assessment of such conditions should be considered during the procedure for grading a beach.

- It is important that water managers use these guidelines judiciously, and carefully consider where they can be applied.

These guidelines are not intended to be used as the basis for establishing conditions for discharge consents, although they may be used as a component for decision making. See the Introduction of these guidelines for discussion on what this document covers.

The microbiological water-quality guidelines for recreational shellfish gathering are as defined in the Shellfish Quality Assurance Circular (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry 1995) for areas of approved shellfish-growing waters. These guidelines are used by the shellfish export sector and are internationally accepted as indicating that shellfish grown in such classified waters under given conditions of sanitary safety are expected to have suitable microbiological quality for public consumption.

Note: These recreational shellfish-gathering water quality guidelines only cover microbiological contamination. They do not cover marine biotoxins, which in certain places and locations can pose a significant risk to recreational shellfish gatherers.

F.1 The preferred indicator for waters used for shellfish gathering

The guidelines use faecal coliform indicator organism values to denote the potential presence of pathogenic bacteria, viruses and protozoa.

F.2 Recreational shellfish gathering guideline values

Compliance with these guidelines alone does not guarantee that shellfish grown in waters of this microbiological quality will be safe. The guidelines apply to waters in a catchment where a prior sanitary survey has shown that there are no point sources of pollution of public health concern. The guidelines are solely a management tool to measure any change from the conditions prevailing at the time of assessment.

The guidelines are also useful for assessing the impact of pollution from surface run-off after rainfall, and of tidal movement under storm conditions. Such factors are used to decide when gathering should be curtailed in commercial shellfish-growing areas when weather conditions cause pollution. They are equally applicable for recreational shellfish-growing waters.

The guidelines are set out in Box 3.

Box 3: Recreational shellfish-gathering bacteriological guideline values

The median faecal coliform content of samples taken over a shellfish-gathering season shall not exceed a Most Probable Number (MPN) of 14/100 mL, and not more than 10% of samples should exceed an MPN of 43/100 mL (using a five-tube decimal dilution test).

These guidelines should be applied in conjunction with a sanitary survey. There may be situations where bacteriological levels suggest that waters are safe, but a sanitary survey may indicate that there is an unacceptable level of risk.

Notes:

- The MPN method as described in Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association (current edition), must be used to enumerate faecal coliforms unless an alternative method is validated to give equivalent results for the waters being tested.

- Sampling to test compliance shall be over the whole shellfish-gathering season.

- A sufficient number of samples should be gathered throughout the gathering season to provide reasonable statistical power in testing for compliance for both the median limit and the 90% samples limit.

Part II: Guidelines for Recreational Water Quality

June 2003

© Ministry for the Environment