Clause 3.17: Identifying water takes

[…]

take limit means the limit on the volume, rate, or both volume and rate, of water that can be taken or diverted from, or dammed in, an FMU or part of an FMU, as set under clause 3.17.

Meeting the environmental flows and levels requires councils to restrict the taking, damming, diverting and discharging of water through ‘take limits’.

Take limits must:

Where a regional plan or water permit allows the taking, damming, diversion or discharge of water, it must identify the flows and levels at which these activities will be restricted, no longer allowed, or in the case of discharges, required (clause 3.17(3)).

Take limits must also:

These provisions work closely with Policy 11: Freshwater is allocated and used efficiently, all existing over-allocation is phased out, and future over-allocation is avoided. This has been retained from previous versions of the NPS-FM. The provisions also link to the requirements in clause 3.28 to provide for the transfer of water takes and how to improve efficiency of water use.

An important part of the definition of ‘over-allocation ’ or ‘over-allocated’ is where resource use exceeds a limit and where an FMU or part of an FMU is not achieving an environmental flow or level set for it under clause 3.16. ‘Limit’ includes a ‘take limit’. Take limits act in tandem with other restrictions such as cease-to-take flows. For example, it may be environmentally conservative to allow a large rate of take for filling a storage pond during higher flows, in order to limit water abstraction at lower flows. However, this would require applying a cease-to-take flow to stop filling of the storage outside relatively high flows. In this situation, two cease-to-take limits would be applied: one to limit water abstraction at lower flows and the other to high-flow harvesting.

In combination, these definitions mean that councils cannot make rules or grant resource consents that allow the taking, damming or diverting or water to exceed the take limit. Takes or diversions that would exceed the take limits should have an appropriate rule structure that avoids over-allocation (eg, prohibited). The NPS-FM now requires plans to state whether flows or levels will affect existing resource consents (clause 3.17(1)(c)). This allows permit holders to assess the effect of that requirement on their water use, and make submissions to the council during the planning process. The plan may also state that permit holders can comply with the terms of the rule, or rules, in stages or over specified periods.

In healthy rivers it may still be possible to reallocate water and achieve the long-term visions and Te Mana o te Wai. However, when there is degradation, the first priority is to restore the water body. This may mean permit holders either have their allocation reduced or face more frequent restrictions.

Any water allocation to new users must come from reducing existing takes and ensure flows and levels are restored over time. Opportunities to reduce takes could come from more efficient water use (using less water for the same use) or water storage (either from water harvesting at high flows, or harvesting and storing rainfall). Councils must consider these options with tangata whenua and their communities.

If achieving new flows and levels means reducing the existing takes (lower take limits), water use may need to be reduced. More efficient use (Policy 11 in the NPS-FM) may be one method. If this is not enough, existing takes may need to be reduced, with some reallocation of water.

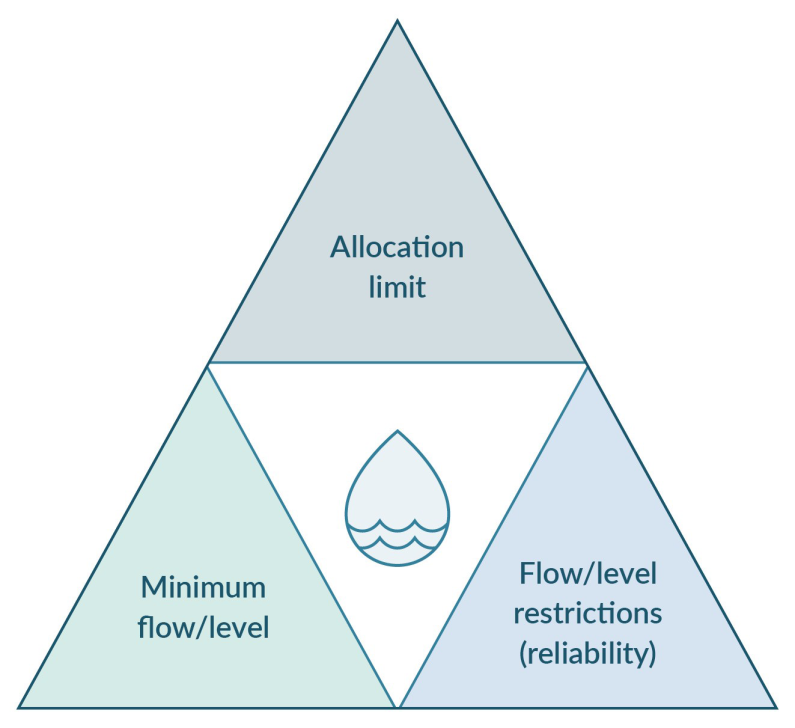

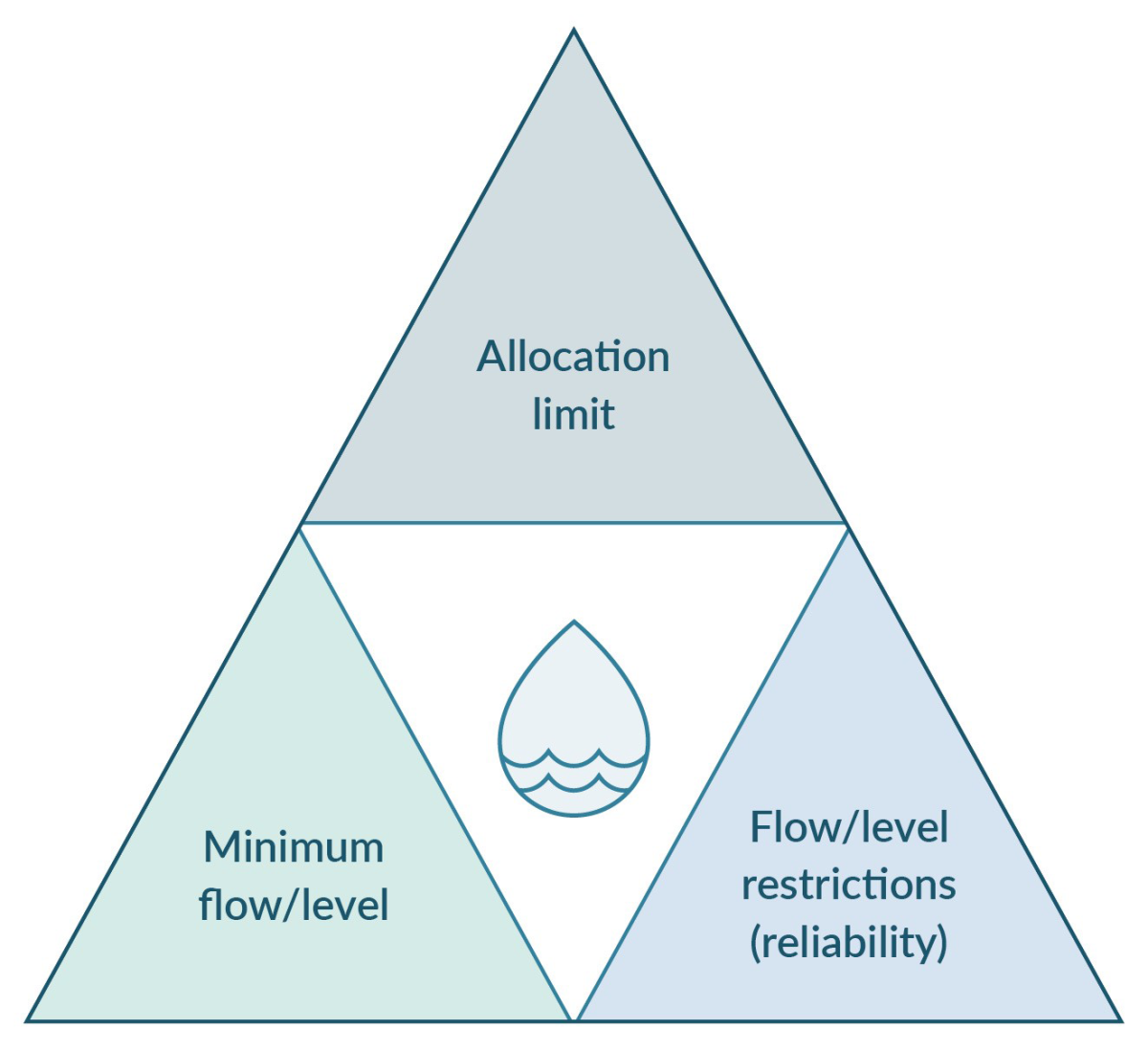

Figure 10 shows the tension when allocating water between:

Councils must follow Te Mana o te Wai when allocating water. Priority goes first to the health and well-being of water bodies and then to people’s health needs. Within the ‘other well-being’ matters, the community may choose its priorities, consistent with Te Mana o te Wai.

If a water body is over-allocated, councils may need to phase in the reduction over a period of years. This will allow users time to adjust. There will be implications for users (eg, irrigators). Councils should be upfront with the community about the reductions.

Water storage is an option to use non-critical parts of the flow during low-flow periods when the water body is not stressed, which increases the allocation back to the river.

Stored water must not be used to expand or intensify land use that would breach the resource use limits. Councils must clearly set out the limits on total land use and intensity for different land types in a catchment.

Clause 3.17: Identifying water takes

July 2022

© Ministry for the Environment