Clause 3.14: Setting limits on resource use

Limit setting is one of the last steps in the NOF process. It must be done well for the instream TASs and concentrations to jointly achieve the environmental outcomes.

This step has proven to be complex and difficult. A robust set of regulatory limits will control cumulative effects, because they clearly set out when and how to stop allocating or using the resource. They also clarify how much resource use to reduce in over-allocated catchments, to achieve the sustainable amount of resource use that will meet water body outcomes.

The phrase ‘resource use’ has been part of the definition of a limit since the first Freshwater NPS in 2011. It links back to the purpose of the RMA to promote sustainable management, which means managing the use, development and protection of natural and physical resources.

A limit on resource use is defined in clause 1.4 as “the maximum amount of resource use that is permissible while still achieving a relevant target attribute state or a nutrient outcome needed to achieve a target attribute state (see clauses 3.12 and 3.14)”. It is intended to be directly about use of resources, and specifically restricting the amount of that use, so that a particular environmental outcome or TAS is achieved and maintained over time.

‘Resource use’ can encompass many different types of use and can relate to:

For water quality, the concept of resource use is potentially broad. Examples could include:

The methods to set limits must:

Limits on resource use are a tool to achieve a TAS and a nutrient outcome needed to achieve a TAS. This leads to a cascade of desired consequences:

A limit on resource use is defined as the maximum amount of resource use that is permissible while still achieving the relevant TAS and nutrient outcomes needed to achieve a TAS. It enables communities to use resources, but limits use to a level that can support the health and well-being of freshwater.

Limits on resource use can apply to a whole region, all or part of an FMU, or even a specific water body or individual property.

The limits can apply to input, output or land use.

Limits on resource use must:

Resource use is often discussed in terms of discharge of contaminants. However, councils should take a broader view of resource use to set limits for some attributes.

In the past, some councils have mistakenly assumed that controls set on a water body are limits. However, this is where TASs and maximum concentrations are set (eg, the maximum instream E. coli concentration at a specified location). These are not limits. The limit for E. coli will be the total set of rules in the regional plan, which limit resource use to achieve the in-water body TAS for E. coli.

The amount of resource use allowed must ensure that the TASs and Te Mana o te Wai are achieved. A limit cannot, individually or cumulatively, allow the TASs to be undermined or prevent them being achieved in the timeframe set.

There is a strong link between limits on resource use and the direction in Policy 11 in the NPS‑FM to avoid over-allocation and to phase out existing over-allocation.

Over-allocation is defined (in part) as a situation where resource use exceeds a limit. Once a limit is set, the regional council must ensure it is not exceeded. If it is currently exceeded, the council must phase out the over-allocation. This is done using a ‘sinking-lid’ limit: a limit that caps the use at the level it is currently allocated (or used, if not all allocated resource is used), and lowers the limit in steps over time. This way, the limit will be lowered gradually to allow for the allocation to be clawed back from current users, or not renewed up to the point where the resource is no longer allocated.

Limit: A total allowable length of unfenced riparian margin.

If stock access to water is thought of as a ‘use of the resource’, then by restricting that access we are imposing a ‘limit’ on stock access to rivers (to reduce faecal contamination).

The limit might be expressed as ‘50 per cent of stream length in a catchment must be fenced’. Individual farmers could ‘trade’ fencing extents.

Conversely, a limit might be expressed as a prohibited activity with a zero allocation.

Limit: A maximum stocking rate to meet an E. coli freshwater objective.

If grazing is the ‘resource use’ and a maximum stocking rate for the catchment is stipulated, that is a ‘limit’.

Although the NPS-FM gives councils flexibility in limit setting, the NPS-FM framework provides guiding principles.

Applying fertiliser to land may be prohibited above a certain amount per hectare, or at certain times of the year, or in certain weather conditions.

The regional council will set the maximum amount, and its conditions, at a level that allows the water body to meet the TAS within the timeframes.

A limit may be defined at different scales, including:

The steps could include the following.

TASs and limits are two essential components of the NPS-FM 2020. They are sometimes thought of in the same way, but in the NPS-FM they are about different things, and the distinction is important.

A TAS is a measurable description of the intended instream state, the freshwater and the ecosystem. It is expressed in units as in the attribute table of the NPS-FM (eg, mg/L).

A limit is a restriction on an amount of resource use, which allows that TAS to be achieved, and nutrient outcomes needed to achieve a TAS.

Limits are not set on measures of water body health (or instream concentrations) but on the activities that affect those measures.

In setting a limit to achieve a TAS, the main question is: ‘What actions must we take or restrict to achieve the TAS?’. For example, a limit is not the amount of deposited sediment in a river. It is the constraints that have to be put on resource use so the amount of deposited sediment is no higher than the TAS for that location. This will require limits on sediment generating activities, such as on the amount or scale of earthworks or vegetation clearance in a catchment, or requiring sediment detention. Deposited sediment is also influenced by flows, so councils must set environmental flows and take limits at a level that allows sediment to be flushed from the river, before it reaches a level that would breach that of the TAS.

It may be hard for councils to estimate what the the effect on deposited sediment will be, if these changes are made. This means that the first time limits and other methods are set, they may be based on very general estimates and assumptions that the methods will be a move in the right direction toward the TAS. As indicated in the earlier detail on Clause 1.6: Best available information and the NOF, uncertainty about data or expected outcomes warrants a precautionary approach. This can mean building a more conservative buffer into a limit to ensure the achievement of incremental movement towards achieving a TAS

When more information becomes available from monitoring councils can adjust their limits and methods to increase the likelihood of reaching the TAS. This finetuning of the limits and other methods to achieve the desired outcome is an iterative process, one that will be informed by both monitoring data and new knowledge that may become available.

For some types of resource use, a limit will need to achieve multiple target states.

Limits on sediment-producing activities will help to achieve the TAS for:

A direct relationship between limit and attribute is not required, rather a suite of limits will achieve a suite of TASs.

When a limit helps to reach multiple TASs, it should be set at a level to meet the most stringent for that location. This way all target states will be achieved.

The first step is to understand the current amount of use. A second step is to establish the maximum amount of resource use that could occur while still meeting the TAS.

Figure 7 shows that the current resource use only informs the starting point for making reductions. It is not material to deciding the sustainable maximum amount of contaminant or whom the resource use should be allocated to and in what quantity.

A limit must be expressed as a rule in a regional plan. Whether or not it has been exceeded is important to understanding if over-allocation has occurred. However, over-allocation can also occur when a limit has not been exceeded, in the case of degradation (see clause 1.4). To be a ‘good’ rule, and to allow an assessment of over-allocation, it must be possible to objectively measure, survey or estimate a limit. It should be clear, certain and capable of consistent interpretation. Where possible, a limit should be based on a numeric or other quantifiable amount.

To determine the limit for a resource, councils and tangata whenua must use the best information available. The total allocated limits on a resource must add up to no more than the total amount of resource use that a catchment’s water body can assimilate. That means using limits that only control a part of the use of a resource will not be effective nor sufficient. Uncertain estimates must err on the side of caution, to protect the health and well-being of water bodies and freshwater ecosystems.

The purpose of a limit is to ensure a TAS or a nutrient outcome needed to achieve a TAS is met or achieved within the timeframe. Without limits on resource use set through rules in a regional plan and – where necessary – restrictions on consents, TASs are just numbers in the plan, with no clear pathway to achieve them. Therefore, an effective limit must have a direct or indirect link with a TAS.

For some attributes that relationship is obvious, such as limits to the amount of nutrients in point source discharges to achieve the TAS for nutrient levels in rivers.

For other attributes this relationship is not so direct. For example, to achieve a TAS for dissolved reactive phosphorus, an appropriate limit might be restricting land use practices that generate sediment containing phosphorus. Interim TASs need to be set for all the intermediate steps to achieve the long-term vision and environmental outcomes.

Interim target attributes are treated the same as the ultimate TAS (clause 3.11(6)(b)) so limits must be set that achieve each interim target over time. Limits do not have to achieve the ultimate TAS immediately, stricter limits can be phased in over time, so long as the interim targets are met. This allows for spreading change over time, which will assist with the transition when large changes to resource use are needed.

A limit places constraints on resource users. These do not have to all come into effect at the same time. But clarity about what future reductions and allocations to expect will give greater certainty to both current and future users to plan for their resource use.

If a limit is placed on stocking units, these reductions can be gradual, giving land users clarity on the scale of these reductions for more effective business planning.

The NPS-FM only requires limits be set through rules in the regional plan. This is sometimes misunderstood to mean that these limits are only set for the time that the plan is in force. TASs will often need more time – or the life cycles of multiple plans – to achieve the long-term vision, so rules that set limits will be set without an end date. During each plan review, limits will need to be reassessed to establish whether they are set at the right level to achieve the TASs.

The likelihood of having to reassess the limits to accommodate the effects of climate change, or because better information is available establishing the relationship between the pressures and the instream state, should be identified when the limits are first established and set in regional plans or on resource consents. This will help reduce expectations that the limits will be permanent. Without this critical information, resource users in highly over-allocated catchments may mistakenly believe they will not face further future reductions. Although councils may not yet know the future levels needed for the limits and other methods, they should reveal the reductions in contaminant load to meet final target states. This information is required in the RMA section 32 analysis. However, it should be kept front of mind and may be best placed in action plans. This should set out future ‘end-state’ limits and future contaminant loads and constraints with likely associated land use, and reveal the extent of expected changes to intensity and land use.

Considering the impacts of climate change when setting limits is one element of achieving Policy 4 of the NPS-FM. This policy is to ensure that all freshwater is managed as part of New Zealand’s integrated response to climate change.

When setting limits, the regional council must have regard to the foreseeable impacts of climate change (ie, adapting to climate change).

Given the recent evidence towards more frequent and severe weather events in New Zealand, failure to consider the effects of climate change will lead to poor planning and poor implementation of the NPS-FM.

For example, when planning for the maximum amount of water takes, also consider available modelling on the frequency of drought in the future. Drought will change the amount of water that can be allocated to sustain (maintain or improve) aspects of freshwater and freshwater ecosystems.

Councils should also consider the expected frequency of floods when deciding on methods to achieve outcomes that could mitigate climate change effects, such as restoring wetlands or larger riparian margins.

Limits must be set to meet the TASs. This does not necessarily equate to one limit for each TAS. Rather, the set of limits (together with the action plans and consent conditions) should lead to a set of target states. These in turn lead to achievement of the freshwater objectives.

There may be situations where a TAS requires a range of limits to meet it, or one limit might meet several TASs. What matters is whether the set of limits in combination with any relevant action plan or consent condition will achieve the corresponding set of target states.

Generally speaking, each TAS should be met via a combination of limit rules, action plans and other methods. In other words, meeting the limit may require a suite of regulatory and non-regulatory methods.

The following questions should be considered.

Limit setting is the step in the NOF where planning decisions begin to directly affect resource users. It is where decisions are made that will determine who will be most affected in the community and how and to whom the cost is allocated of achieving the environmental outcomes the community seeks. It is therefore the most challenging and potentially controversial step in the ‘values–environmental outcomes–limit-setting’ cascade.

It is best practice to give maximum clarity to the community and resource users. Where there is over-allocation, and reductions in contaminant loads are required, it is best practice to ensure that the complex and challenging decision-making process around what actions are required to achieve these are clearly identified in the plan, rather than devolved to individual decision makers through consents or farm plans. The plan should provide as much clarity as possible on the required reductions, and on possible changes in land use, land intensity and practice changes.

It must be likely that limits ‘add up’ to not more than the total contaminant load required to meet the TAS, and that they will be hard and enforceable. In the past, limits have not added up from the farm scale (individual resource use allocation) to the catchment load scale (total limit). Even though every attempt should be made to set a limit as accurately as possible, it will always be an estimate. ‘Adding up’ the allocated uses (and loads) should use the best available information and best estimates.

However, once the best estimate is agreed, with enough certainty that it will achieve the TAS, councils must provide a high degree of certainty that the rules themselves will achieve the load limit or reduction.

Councils need to create a hard limit to ensure there are no unintended cumulative effects. To do this, Good Management Practice (GMP) may often not be enough, because it does not address the scale of the activity in the catchment.

The choice of method, or combination of methods, is also important when determining how to regulate and cap contaminant loads. For instance, using GMP on its own will not create a hard limit. It may result in a useful and tangible set of reductions to address some portion of over-allocation, if the standards are clear and enforceable and applied well, but GMPs are practice standards and do not generally ‘limit’ either the extent or intensity of land uses.

Limits should be applied to three critical parameters of resource or land use to be effective. These are controls on: land use practice, and the extent and intensity of land uses where they leach contaminants beyond the land’s assimilative capacity.

Limit setting is highly technical and requires analysis by experts including scientists, planners, economists, mātauranga Māori experts and consenting officers.

The complete set of limits and methods must meet all the TASs, which (alongside take limits) will achieve the environmental outcomes. Ultimately, these will achieve the long-term vision and give effect to Te Mana o te Wai and its hierarchy of priorities.

A TAS must be set at baseline state or better, and the health and well-being of water bodies must be at least maintained, and, in some cases, improved. It may not be possible to allow for additional resource use (above the current level).

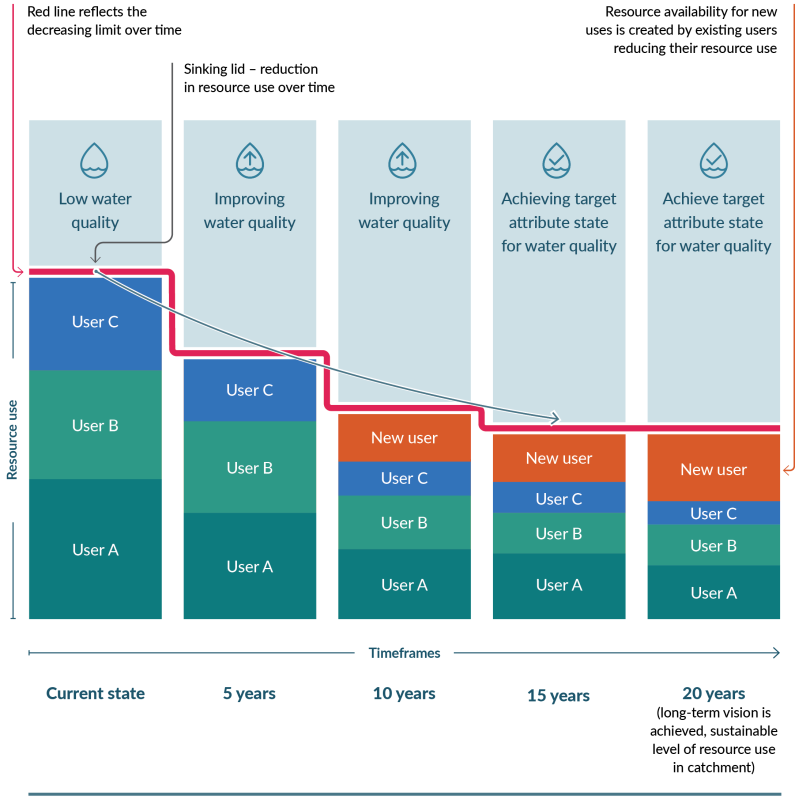

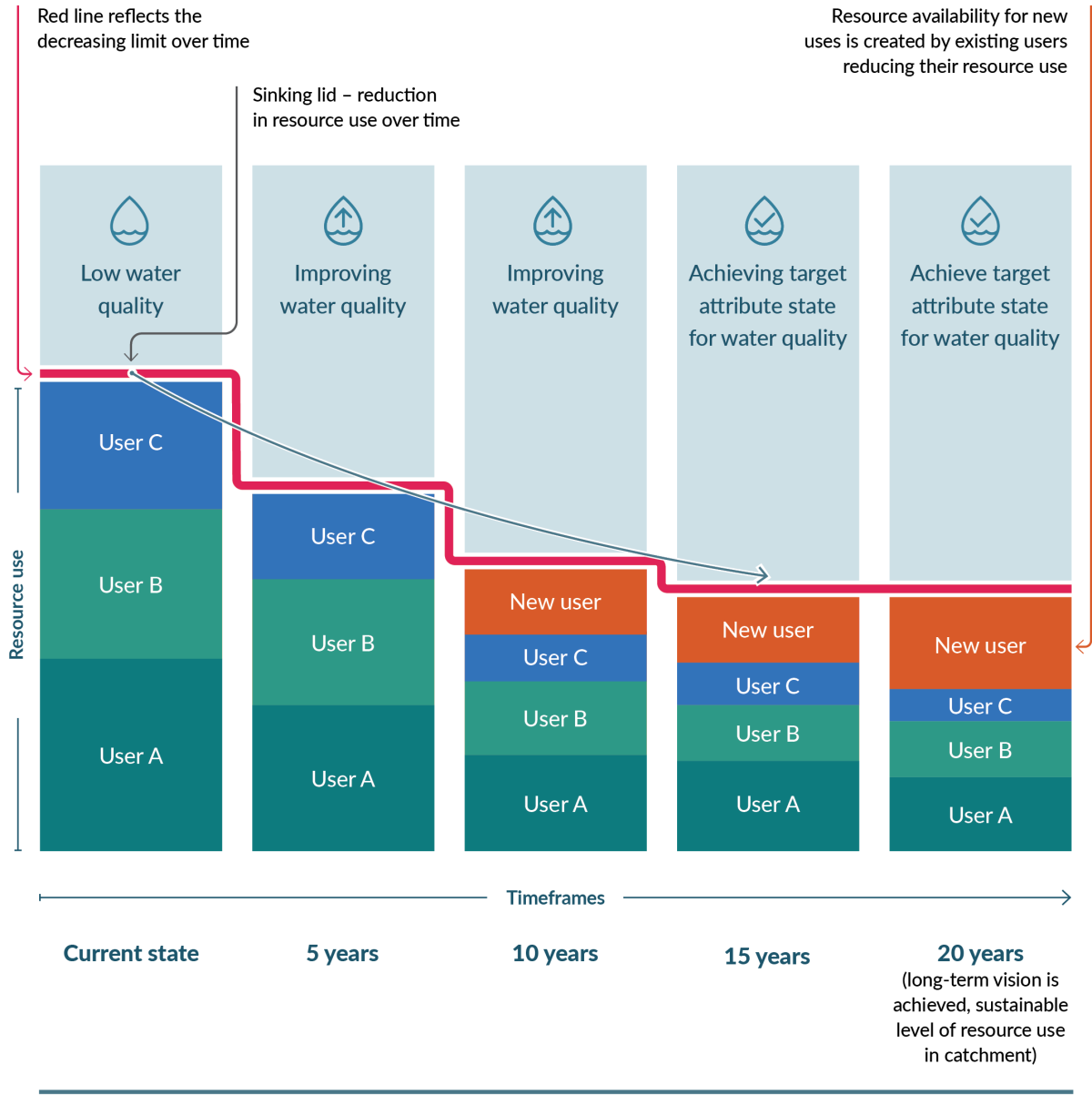

If the community seeks growth in particular kinds of resource use, the limits may accommodate new users while still achieving the TAS. Figure 7 illustrates this.

Infographic illustrating a hypothetical scenario where there is a decrease in resource use leading to an improvement in water quality at 5-year intervals.

Low water quality

At the current state there is high resource use, as the corresponding limit allows users a greater amount of resource use.

Improving water quality

After 5 years, the total combined resource use has decreased with the decrease in individual resource use.

After 10 years, the total combined resource use has decreased further, but at a lesser rate. This has occurred alongside all current users reducing their resource use and a new user being able to take resource.

Achieving target attribute state for water quality

After 15 years, the total combined resource used has reduced further at an even smaller rate. This has occurred alongside all current users reducing their resource use and no change in the amount of resource taken by new resource users.

Achieve target attribute state for water quality

At 20 years, the total combined resource use has remained the same. Existing users have further decreased their resource use, which has made resources available to new users.

Infographic illustrating a hypothetical scenario where there is a decrease in resource use leading to an improvement in water quality at 5-year intervals.

Low water quality

At the current state there is high resource use, as the corresponding limit allows users a greater amount of resource use.

Improving water quality

After 5 years, the total combined resource use has decreased with the decrease in individual resource use.

After 10 years, the total combined resource use has decreased further, but at a lesser rate. This has occurred alongside all current users reducing their resource use and a new user being able to take resource.

Achieving target attribute state for water quality

After 15 years, the total combined resource used has reduced further at an even smaller rate. This has occurred alongside all current users reducing their resource use and no change in the amount of resource taken by new resource users.

Achieve target attribute state for water quality

At 20 years, the total combined resource use has remained the same. Existing users have further decreased their resource use, which has made resources available to new users.

Figure 7 gives an example of a water body for which the resource and land use or output in an FMU (on the land) is over-allocated. This figure shows a scenario whereby a council restricts total resource use, for example, through a combination of imposing input controls (the amount of fertiliser that may be applied), land use controls (restriction on earthworks near water bodies) and output controls (volume and timing of wastewater discharge). The first bar of the figure shows that there is low water quality due to a combination of too much resource use, and/or a lack of restriction on resource outputs and land use.

The council has set limits, with five-year intervals, in its plan to achieve the long-term vision in 20 years. Using a ‘sinking lid’, over 15 years, the maximum resource use and outputs are lowered and land use is controlled to minimise contaminants. This example shows a five-year lag between sustainably managing the resource (for instance, in lowering nitrogen by capping stock numbers) and achieving the long-term vision. This lag occurs because restoration of ecosystem health is not instant, after reduction of resource use.

The space below the red line shows how much total resource use is allocated to users and how this gets lowered over time. The space above the line depicts the water quality in relation to resource use. Water quality increases as the limits on resources are controlled and managed.

The sinking-lid red line indicates the limits needed to achieve the interim TAS. However, as long as the use allocated to the waterbody (Te Mana o te Wai priority 1) above the line stays within the requirements and timeframes for the interim TAS, the use below the line can be allocated to resource use within the two other priorities. In this example, the use allocated to the waterbody serves priority 1. The use allocated to users A, B, C and the new users falls under priority 3.

In the 10-year timeframe, users A, B and C have reduced their use beyond the limit, to the extent that some resource use can go to a new user, while total resource use stays within the limits to reach the interim TAS.

Any new resource use will need to come from reductions in existing use. For example:

These options need to be considered with tangata whenua and the wider community engaged in the process. There may be additional costs, and who these fall to and over what period should be part of the discussion.

When the maintain or improve policy requires a contaminant load to either decrease or remain the same, there may seem to be no room for allocating the resource use to new users. However, this is not clear cut. Resource use can be freed up within the limit threshold by reallocating part of the current use to new users. This can only happen within the reductions required to achieve the TAS and Te Mana o te Wai.

Clause 3.14: Setting limits on resource use

July 2022

© Ministry for the Environment