New Zealand is recognised internationally for its stunning landscapes and productive agricultural and horticultural land. Since human settlement, the way we have used our land has fundamentally shaped our nation.

Land use and our economy

Land underpins a significant part of our economy. Seventeen per cent of New Zealand’s gross domestic product depends on the top 15 centimetres of our soil.

Land plays an integral part in supporting New Zealand’s top two export earners: tourism and primary production. In 2007, agriculture, forestry, horticulture, and viticulture generated $16.1 billion, $3.6 billion, $2.5 billion, and $662 million respectively in export earnings. In 2006, tourism generated $8.3 billion in export earnings.

Land cover

Reflecting changes in land use, land cover in New Zealand continues to change as our population grows, land prices change, and international commodity prices fluctuate.

In 2002, natural land cover (native forest, native vegetation, and other native land cover, for example, rivers, lakes, snow, ice, and scrub) was New Zealand’s largest land cover at 50 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area. Pasture was our second largest land cover at just over 39 per cent. Exotic forest covered 7.31 per cent of New Zealand’s land area.

Between 1997 and 2002, satellite measurements showed that:

-

pastoral land cover decreased by 125,200 hectares (or just over 1 per cent)

-

human settlements increased by just over 5,300 hectares (or 3 per cent)

-

native vegetation and native forest decreased by 17,200 hectares (or 0.15 per cent)

-

exotic forest cover increased by 139,500 hectares (or about 8 per cent)

-

horticultural land area increased by 4,500 hectares, with the total area of horticultural land remaining at just under 1.6 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area.

In 2006, the total land area of planted forestry was estimated to be 1.8 million hectares. From 1990 until 2003, a trend of increasing land area in exotic forestry was observed.

Land use

In 2004, pastoral land use (for example, sheep, beef, and dairy farming) was New Zealand’s largest human land use at just over 37 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area.

Although the total area of New Zealand land in pasture has been decreasing since 1972, the area of land in dairy pasture has increased. Between 1996 and 2006, the national dairy herd has grown by 24 per cent. This intensification of agricultural land use has occurred as farmers have responded to economic signals by converting suitable dry-stock pasture, exotic forestry, and existing dairy farms into more intensive dairy farms.

A change to more intensive farming in some regions has resulted in:

-

further reduction of freshwater quality in lowland rivers and waterways

-

changes in soil health

-

increases in some greenhouse gases, for example, methane.

Over the past 10 years, greater diversification of land use has been evident, especially for horticultural land including vineyards, orchards, and perennial crops. As an example, the area of land in vineyards increased by 28 per cent between 1997 and 2002.

From the mid-1990s, there has been a significant reduction in the amount of new exotic forestry plantings. In 2005, the rate of new exotic forest plantings declined to its lowest level since 1959. In 2004, a new trend of not replanting exotic forestry after harvesting became apparent. In addition, some planted exotic forest planting has been converted to pastoral land use before maturity.

Hill-country erosion

Hill-country erosion is estimated to cost New Zealand between $100 million and $150 million each year through the loss of soil and nutrients; loss of production; damage to houses, fences, roads, phone and power lines; and damage to waterways and aquatic habitats. About 10 per cent of New Zealand is classed as severely erodible.

During the 1990s, hill-country erosion eased in some regions. Satellite measurements between 1997 and 2002 showed that 36,400 hectares of land on erosion-prone hill country was converted from pasture to other land covers during this period. The large majority of this (36,300 hectares) was converted to exotic forestry or retired and left to revert to scrub.

Land use affects the environment

Land use puts many different pressures on our environment.

-

Urban and rural run-off pollute our waterways and coasts.

-

Urban expansion can lead to the loss of land for food and fibre production or the loss of plant and animal habitats.

-

Intensive farming (with high animal stocking rates and increased use of fertilisers) can have detrimental effects on groundwater and surface water quality.

-

Intensification of agricultural activity can also increase greenhouse gas emissions from animals.

Land use and soil health

Intensively cropped soils (such as market gardens) have lower organic content and poorer soil structure compared with pasture soils, and very high nutrient levels. High levels of available phosphate were also observed under some croplands, reflecting application of fertilisers.

Soils under exotic pasture generally have higher nutrient levels and are less acidic than forestry soils, reflecting the use of lime and phosphate fertilisers to develop agricultural land. Under some dairy farming soils, phosphate levels are high and some forms of nitrogen may be reaching saturation point. When nitrogen levels reach saturation point, excess nitrogen can be leached from soils, affecting water quality. Nitrogen and potentially mineralisable nitrogen were highest under pastoral land use than any other land use.

Monitoring found moderate soil compaction on a large proportion of monitored pastures and some cropping land uses. Soil compaction is caused by farm animals treading on pastures, and vehicle traffic and cultivation on croplands. Compaction can reduce pasture growth and increase rates of nutrient run-off to waterways.

Soil pH (acidity or alkalinity) under exotic forests was found to be similar to that under native forests. Other agricultural land uses exhibit higher pH values (are more alkaline).

Past uses have contaminated some land

New Zealand soils generally contain low levels of contaminants, but past industrial, domestic, or agricultural activities have contaminated some sites. Local government is working to identify these sites and ensure they are appropriately managed.

Our understanding of the extent of land contamination in New Zealand has improved, but a substantial amount of work is still required:

-

to assess sites identified as potentially contaminated

-

to record information about contaminated sites in a consistent format.

Legislation such as the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 has been enacted to prevent the present-day contamination of land.

Past, present, and future management

Historically, environmental management of land in New Zealand has focused on:

-

managing hill-country erosion

-

minimising flood risk

-

improving the health of pasture soils.

More recently, greater focus has been placed on:

-

protecting riparian stream margins

-

excluding stock from waterways

-

minimising nutrient enrichment of our waterways, including through nutrient budgeting and use of nitrification inhibitors

-

protecting our land-based primary production sector from pests and diseases from overseas.

Looking ahead, focus is likely to sharpen on how best to:

-

manage the impacts of intensified land use on our soils and waterways

-

identify and manage land contaminated by historical agricultural and industrial activities

-

continue to manage hill-country erosion

-

continue to manage biosecurity risks to New Zealand’s primary production sector and native species

-

meet growing consumer demand for sustainably produced agricultural, horticultural, and forestry products.

The way we have used our land has fundamentally shaped our nation. From earliest times, settlers in New Zealand have worked the land to produce food and fibre (for example, wool and flax), to raise animals, and to build dwellings. Today, New Zealanders value land for its scenic, recreational, historical, and cultural significance.

A definition of land

Land is considered to include:

- the aesthetic components of landform and landscape including the vegetation cover

- the physical components of soil and parent material (the soils and underlying rock types that give rise to soil)

- the plant and animal communities in the soil, such as insects, mites, springtails, nematodes, worms, fungi, bacteria, and algae

- the exotic and native ecosystems resident on the land, such as exotic forestry, urban settlements, native forests, and tussock grasslands. (Williams and Mulcock, 1996.)

Landform and landscape

Landforms are the result of geological processes and chemical and physical weathering. Landforms interact constantly with living and non-living features such as plants and waterways to make up a landscape.

New Zealand’s geological history has resulted in signifi cant variations in landscape from dry plains, to steep hill country, snow-capped mountains, and coastal dunes. Even within a few kilometres, neighbouring landscapes can differ greatly. Except for the occasional large earthquake, volcanic eruption, forest fi re, or extreme storm event, the natural factors that created and continue to change New Zealand’s landforms tend to operate slowly over hundreds, thousands, or millions of years.

Today, New Zealand’s landscapes include both cultural landscapes (those modifi ed by people) and natural landscapes. While both landscapes are subject to constant change, the speed of this change depends on whether the change is due to natural or human infl uence.

Land use defines New Zealand’s identity

Reliance on land resources is a defining feature of New Zealand’s national identity. The expertise we have developed in using our land resources has put New Zealand on the international stage. Land underpins New Zealand’s top two export earners: tourism and primary production.

Our high-value agricultural, horticultural, wine, and forestry products are exported around the world. And, in recent years, New Zealand has marketed itself internationally as a premier destination for scenic and adventure tourism.

Export earnings

In the year ended 31 March 2007, primary production generated export earnings that equated to:

-

agriculture – $16.1 billion

-

forestry – $3.6 billion

-

horticulture – $2.5 billion

-

viticulture – $662 million.

(Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007b; New Zealand Wine, 2007).

In the year ended 31 March 2006, tourism generated export earnings of $8.3 billion (Statistics New Zealand, 2007b).

Primary production

Dairy products were New Zealand’s single largest export earner in the year to December 2006, making up 18.1 per cent of total exports. Meat and timber were our next largest export products, accounting for 13.5 and 6.2 per cent of total exports respectively (Statistics New Zealand, 2007a).

Primary production also provides direct and indirect employment for a significant proportion of the New Zealand workforce, particularly in rural areas.

Tourism

In terms of both export earnings and onshore economic value, international tourism contributed $12.3 billion to New Zealand’s economy in the year ending 31 March 2005 (Ministry of Tourism, 2007).

New Zealand’s changing land cover and land use

‘Land cover’ describes the types of features present on the surface of the earth (Lillesand and Kiefer, 1994). Pastures, snow and ice, forests, human settlements, and lakes are all examples of land cover types.

The term ‘land use’ relates to the human activity or economic function associated with a piece of land, such as built-up areas, commercially planted forestry, and different types of farming or horticulture (for example, dairy, sheep and beef, grapes, berryfruit) (Lillesand and Kiefer, 1994).

Human activity modifies many aspects of the environment, particularly land cover and land use. Before human settlement, forests were New Zealand’s predominant land cover (see chapter 12, ‘Biodiversity’). Since then, New Zealand’s land cover has undergone significant human-influenced change.

New forms of cultural landscapes (those modified by people) were created from natural landscapes. Settlements grew around the river mouths that provided harbours as settlers made use of New Zealand’s most suitable land for economic, social, and cultural development. About 24 per cent of New Zealand’s original native-forest land cover remains today; however, nearly all lowland areas have been cleared of forest for human uses, including agriculture, horticulture, and urban development.

Topography and geology influenced the choice of land use. Thirty per cent of our country is hilly with a slope of more than 25 degrees (Sparling, 2007). Our preference for animal production over crop production reflects the lack of flat land available for cultivation in many areas (Ministry for the Environment, 1997). Climatic variations and soil types also affect land productivity, and have resulted in different patterns of primary production and land use around the country.

New Zealand’s soils

New Zealand has a diverse range of soils and parent materials. This range has been further increased by human activity to enhance soil fertility.

New Zealand soils are naturally acidic with low levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur. Consequently, soils used to grow crops and pasture derived from European agriculture need to be developed and maintained with nitrogen-fixing plants (such as clover), fertilisers and, often, lime to sustain high-yield plant growth. As a result, farmed soils today are not the same as the soils farmed by early settlers (they have different biological, chemical, and physical properties than earlier soils) (During, 1984).

In general, North Island soils are strongly influenced by volcanic ash, with many areas naturally low in minerals such as magnesium, copper, iron, cobalt, and boron. In the South Island, most arable soils come from parent material carried down from mountains and foothills by rivers and wind, aided by glacial action. Mineral deficiencies in South Island soils follow rainfall patterns – the wetter the area, the greater the potential for minerals to be leached out (Hewitt, pers comm).

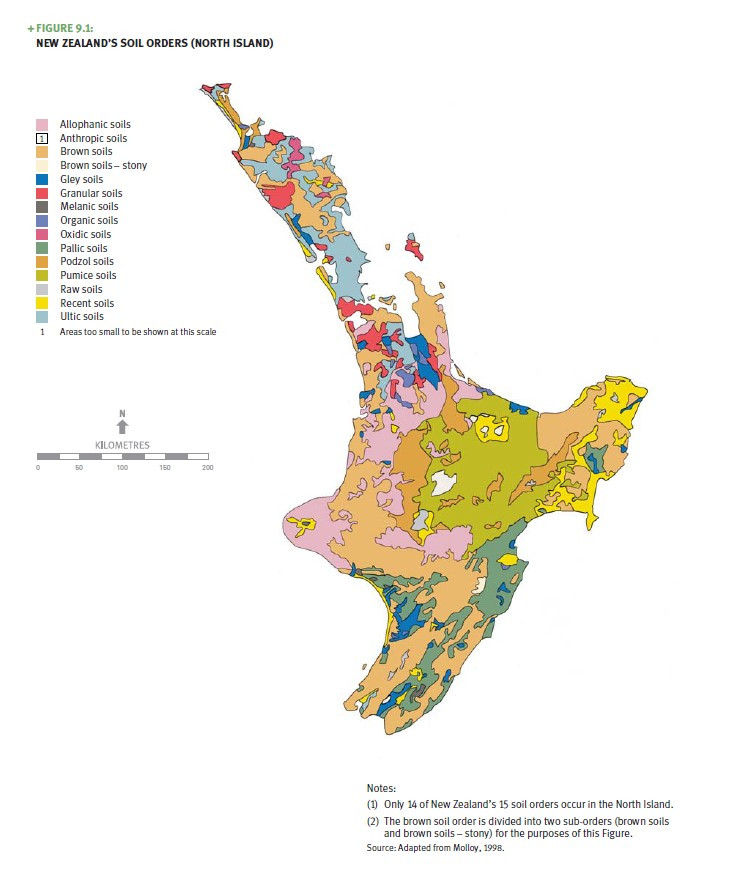

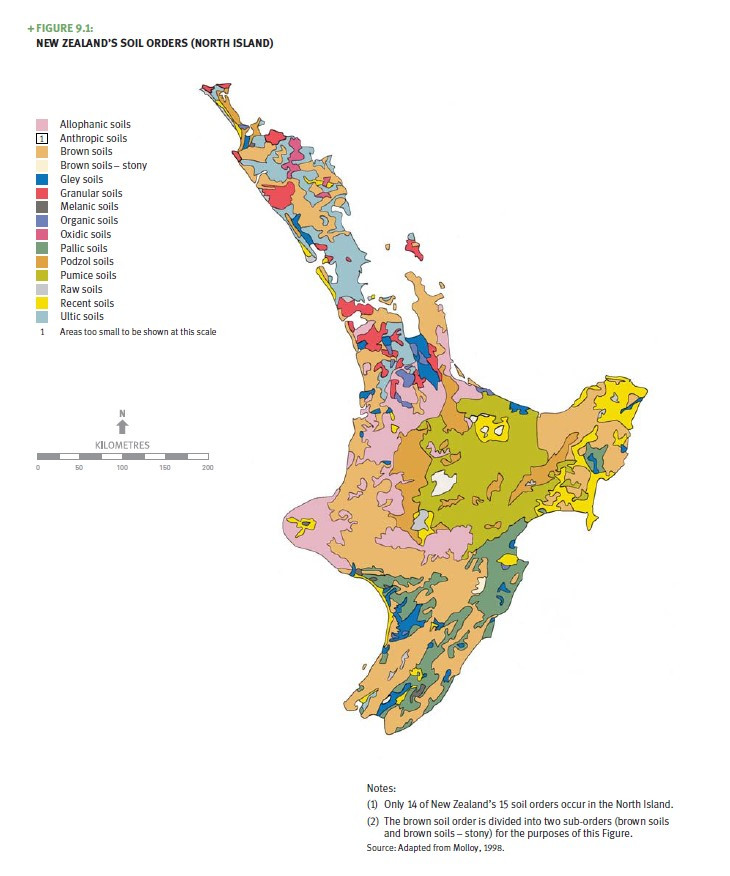

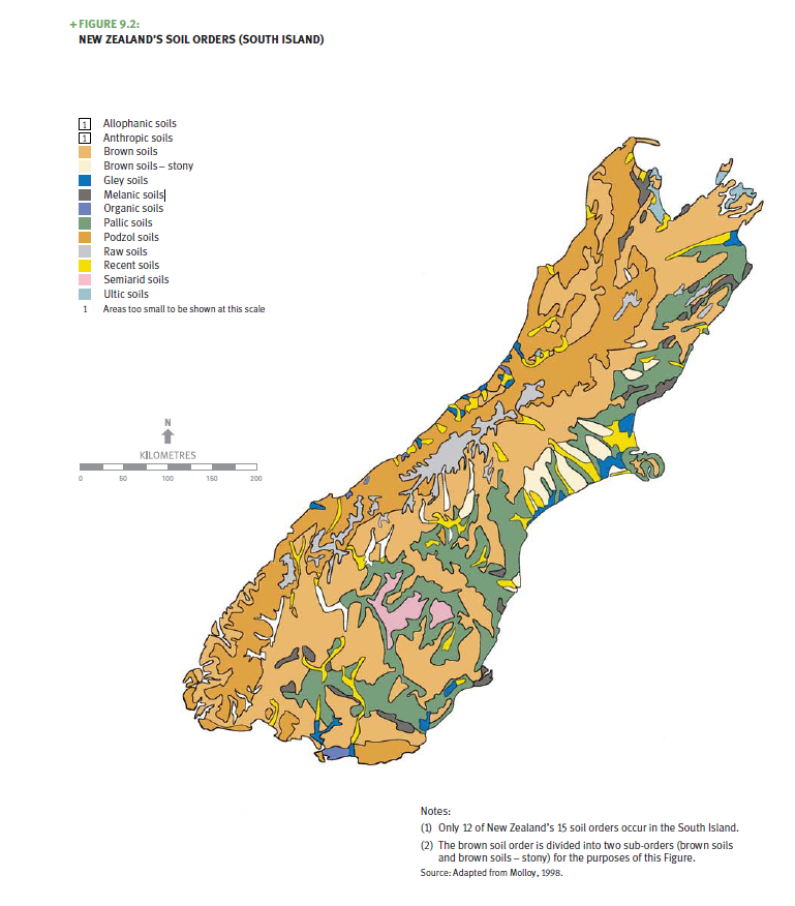

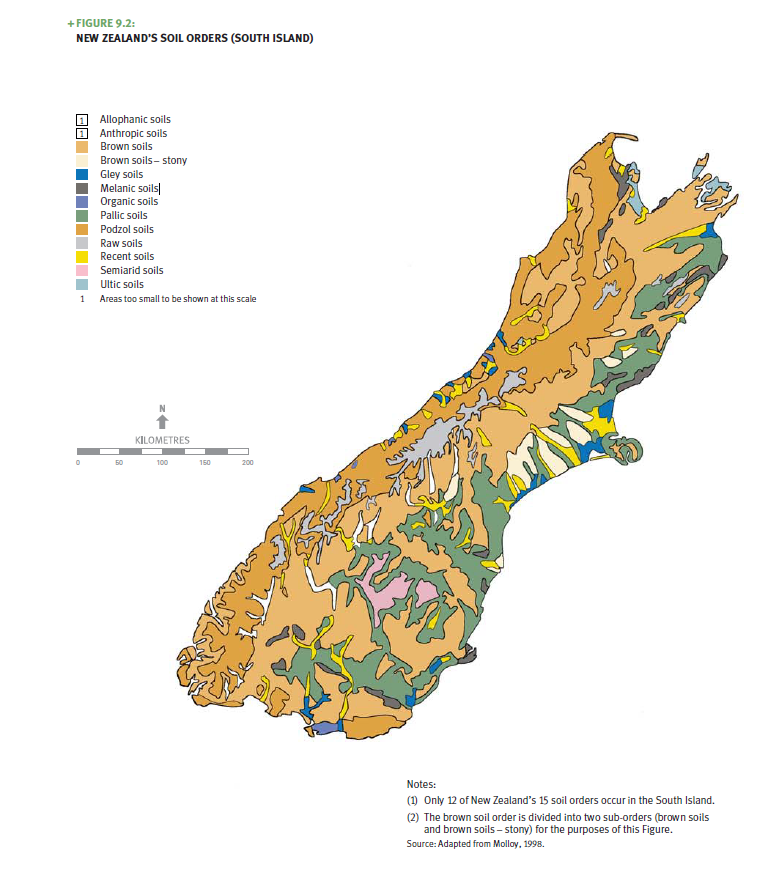

Figures 9.1 and 9.2 show the location of New Zealand’s 15 soil orders – the highest and most generalised level of soil groups in a soil classification (see box ‘More about soil classification in New Zealand’).

Nitrification inhibitors: tackling nitrous oxide emissions from soils

The agricultural sector produces close to 50 per cent of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions (see chapter 8, ‘Atmosphere’).

Around one third of New Zealand’s agricultural emissions are in the form of nitrous oxide. Nitrous oxide is emitted from soil processes. Increased emissions can result from the addition of nitrogen to soils (for example, urine and dung from grazing sheep and cattle, the application of nitrogen fertilisers, and from the absorption (fixation) by clover of nitrogen from the atmosphere).

What are nitrification inhibitors?

Nitrification inhibitors are chemical compounds which stop the conversion of nitrogen into nitrous oxide in soils. These inhibitors can be applied to soil to reduce emissions of nitrous oxide to the atmosphere.

What is the impact of nitrification inhibitors?

Research conducted at a number of sites in New Zealand indicates that the application of nitrification inhibitors to soil results in an average 70 per cent reduction in nitrous oxide emissions when urine is applied to pasture (Di et al, 2007). Similar, although variable, reductions in nitrate leaching have been recorded. Actual reductions in both nitrate leaching and nitrous oxide emissions may be lower in an on-farm environment.

An added benefit is the potential for increased pasture production associated with the reduction in loss of nitrogen. In addition, reductions in nitrogen losses from soils help keep our waterways clean: leaching of nitrates from agricultural soils affects water quality in many areas (see chapter 8, 'Atmosphere and chapter 10, ‘Freshwater').

Research is continuing to evaluate this innovative technology in New Zealand.

Image: Source: Adapted from Molloy, 1998

Image: Source: Adapted from Molloy, 1998

Image: Source: Adapted from Molloy, 1998.

Image: Source: Adapted from Molloy, 1998.

TABLE 9.1: NEW ZEALAND’S 15 SOIL ORDERS AND THEIR PREDOMINANT LAND USES

| SOIL ORDER | REGION OF NEW ZEALAND | PERCENTAGE COVER IN NEW ZEALAND (%) | PREDOMINANT LAND USE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allophanic | Central North Island | 5 | Pastoral farming, cropping, and horticulture |

| Anthropic | Central Otago, Westland | <1 | Modified soils – extensive in urban areas and areas that have been mined |

| Brown | East Taranaki, Whanganui–Rangitīkei, east coast of North Island, Wellington, Marlborough, Nelson-Buller, Southland, and South Island high country | 43 | Intensive pastoral farming and forestry |

| Gley | Wetlands – low parts of the landscape prone to water logging | 3 | High-producing dairy farms (with drainage systems) |

| Granular | Northland, South Auckland, Waikato, and some areas in Whanganui | 1 | Pastoral farming, cropping, and forestry; horticulture in some areas |

| Melanic | Lowland plains on east coast of South Island (some in Northland) | 1 | Pastoral farming, mixed cropping, and market gardening |

| Organic | Lowlands of Waikato and Bay of Plenty wetlands | 1 | Vegetable growing and horticulture |

| Oxidic | Northland, Banks Peninsula, and Otago Peninsula | <1 | Pastoral farming, forestry, and native bush |

| Pallic | East coast of North Island and Manawatū | 12 | Pastoral farming and mixed cropping |

| Podzols | Northland and Westland | 13 | Agriculture and forestry |

| Pumice | Central North Island, Hawke’s Bay, and Bay of Plenty | 7 | Pastoral farming, forestry, and native bush |

| Raw | Central North Island, Hawke’s Bay, and Bay of Plenty | 3 | Pastoral farming, forestry, and native bush |

| Recent (alluvial and coastal) | All districts (floodplains, lower terraces of rivers, and coastal areas) | 6 | Alluvial: dairy farming, arable crops, market gardening, horticulture, and sports fields; Coastal: pastoral and exotic forestry |

| Semi-arid | Central Otago | 1 | Pastoral farming, pipfruit, tussock land, and mountains |

| Ultic | Northland/Auckland | 3 | Urban, pastoral farming, and native vegetation |

Source: Adapted from Molloy, 1998.

Soil classifi cation and its use in New Zealand are explained in the box ‘More about soil classifi cation in New Zealand’.

More about soil classification in New Zealand

What is a soil classification used for?

A soil classification can be used to trace the formation, or evolution, of soils through time. The need for soil classification has been part of human activity in New Zealand. Soil classification has been used in New Zealand since the arrival of the first Polynesian canoe. Māori horticulturalists recognised and named soil classes that were relevant to the establishment and management of their gardens, in particular, kūmara gardens. They recognised classes such as oneharuru (a light but good sandy loam) and onetea (white soil from sandy volcanic material).

Who developed New Zealand’s classification?

The New Zealand soil scientist, Norman Taylor, developed the New Zealand Genetic Classification in 1948, which recognised ‘soil groups’ and related them to the environmental factors that most influenced their character. Knowledge of these relationships helped the prediction of soil classes from observations of geology, landscape, climate, and vegetation. Such predictions enabled rapid progress in the broad-scale mapping of New Zealand soils.

By the late 1970s, Taylor’s classification was becoming outdated. With new information, the New Zealand Soil Classification was developed (see Figures 9.1 and 9.2). Under this classification there are 73 major soil groups that can be aggregated into 15 different soil orders. Soil orders are the highest and most generalised level of the classification. The soil groups can be divided into 272 subgroups with a further subdivision into soilforms. The top three levels of the classification (orders, groups, and subgroups) were described by Hewitt (1993) and the fourth level (soilforms) by Clayden and Webb (1994).

Source: Molloy, 1998.

Factors that affect land

New Zealand’s land is constantly changing. The speed of this change depends on natural or human influences. Land use, a change due to human activity, directly influences land cover. Urban land uses generally go hand-in-hand with artificial land cover such as roadways, pavements, and buildings. Rural land uses generally go hand-in-hand with land cover such as pastures, forests, vineyards, croplands, and orchards. Changing land use and land cover can create pressures on the environment, which in turn affect land-based ecosystems, soils, plants and animals, waterways, and our atmosphere (see chapter 8, ‘Atmosphere’;chapter 10, ‘Freshwater; chapter 11, ‘Oceans’; and chapter 12, ‘Biodiversity’).

Some environmental pressures on land include:

-

changes in land cover that affect land-based ecosystems and native or exotic (introduced) biodiversity

-

changes in land use that affect soil health (that is, soil quality) or soil intactness (that is, the ability of soils to stay in place), and have flow-on effects for water quality in rivers, lakes, estuaries, and the coastal marine environment, and increase the risk of erosion and flooding

-

pesticide, herbicide, and other chemical contamination of soils that result in contaminated land

-

introduced animal pests, diseases, and weeds that affect land-based ecosystems and threaten biosecurity, animal health, productivity, or human health.

Historic land use

Nearly all New Zealand’s cultural landscapes have been modified by agriculture, horticulture or forestry at some time in the past. As in other countries, historic land-use practices have had serious impacts on New Zealand’s environment, including soil erosion (which causes siltation of streams, rivers, and estuaries) and increased flooding risk (see box ‘More about flooding in New Zealand’).

In many areas, the effect of historic land use is only now being felt – it often takes decades for nutrients from farm run-off to reach our lakes and groundwaters, where they cause algal blooms and dense growth of aquatic weeds (Ministry for the Environment, 1996).

More about flooding in New Zealand

About 100 of our towns and cities are located on floodplains. As a result, flooding remains the most common cause of civil defence emergencies in New Zealand.

Although flooding occurred in New Zealand before human settlement, the nature of flooding was changed significantly by the European settlers’ intensive land clearing. The capacity of the land to retain rainfall was reduced by converting forests to pasture. This change caused greater flood peaks, more intensive erosion, and changes in river systems, leading to more frequent and severe flooding.

Early flood protection measures

The importance of protecting our valuable topsoils was recognised in New Zealand in the mid-1900s. The Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941 was introduced to limit soil erosion and the effects of flooding. Most of New Zealand’s large-scale river-control schemes were built under this regime. About 3,000 kilometres of stopbanks were constructed in the 1950s and 1960s alone.

Stopbanks protected communities from regular flooding, but they also allowed more intensive development on floodplains. In some cases, stopbanks actually increased the consequences of flooding, because more people and assets were affected when large floods breached stopbanks. Over time, the traditional approach of building structures to protect people and property from flooding shifted to focusing on planning measures to control development in flood zones.

Integrated catchment management schemes

Integrated catchment management schemes were introduced in the 1970s and 1980s. These schemes put in place soil conservation measures in upper catchments, and river control and erosion protection in the lower reaches of rivers and floodplains. An integrated approach is particularly relevant to dealing with flood risk.

The ‘4Rs’ approach (risk, readiness, response, recovery)

Since 2002, New Zealand has followed a risk management approach to natural hazards, including floods. This approach relies on reducing risk, being ready (risk-preparedness), response, and recovery.

Severe consequences

Widespread flooding in the lower North Island in February 2004 reminded New Zealanders how disastrous floods can be. Heavy rainfall (up to 300 millimetres in 2 days) saw rivers and streams flood in Hutt Valley, Kapiti Coast, Wairarapa, South Taranaki, Wanganui, and Manawatū. Manawatū was worst affected, with 1,800 people evacuated from their homes and farms, and economic losses estimated at $400 million (McSaveney, no date).

Lesser floods can also have significant consequences. In July 2004, flooding in the Eastern Bay of Plenty led to the evacuation of 3,200 people. About 450 farms were affected, and 200 houses were left uninhabitable. Mangawhero River flooding in July 2006 caused a bridge to collapse, isolated the settlement of Mangawai and caused damage estimated at $10 million. (National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, and Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, 2006).

Future management of flooding

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and severity of flood events in some areas of New Zealand, particularly those already prone to flooding. Integrated catchment management and the 4Rs approach to hazard management are particularly relevant to managing future flood risk. Central and local government are working together to meet this challenge.

Changing and intensifying land use

Today, although many land management practices have improved, there remain some significant pressures on the environment from changing and/or intensifying land use.

Over the past 10 years, a change to more intensive farming in some regions has resulted in:

-

further reduction of freshwater quality in lowland rivers and waterways (see chapter 10, ‘Freshwater’)

-

increases in some greenhouse gases, such as methane (see chapter 8, ‘Atmosphere’).

Effects of commodity prices

Changes in land use in our primary production sectors are driven by export prices (Ministry for the Environment, 1997). High market prices for particular commodities (such as milk and dairy products, timber and forestry products, and more recently grapes and wine products) can cause farmers to convert from one land use to another.

Versatile soils

In recent years, the spread of urban and rural lifestyle subdivision in some regions has put pressure on soils known as ‘versatile soils’ (Molloy, 1998). Versatile soils cover about 10 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area. These soils are fertile, generally well-drained, and found on slopes of less than 12 degrees (Molloy, 1998).

Because versatile soils are of high value for food production, they are traditionally used for horticulture or arable cropping. While changing the use of these soils from large scale food production to human settlement may result in a loss of fertile productive land, it also changes the pressures on the immediate land environment.

Horticulture is estimated to cover 1.6 per cent of New Zealand's total land area compared to 24 per cent in Europe.

Source: Ministry for the Environment.

Tourism infrastructure needs

Scenic and adventure tourism, a growth industry in New Zealand, relies on natural and pastoral landscapes and native biodiversity.

Land use for tourism purposes has different impacts on the environment than other land uses. Revenue from tourism can help protect valuable native land cover and biodiversity. The infrastructure needs associated with tourism (such as roads, accommodation, and waste management) place different pressures on our land than other land uses (for example, primary production). However, tourism can have a wider positive environmental impact when the tourism demand is for a ‘clean and green’ environment.

Vulnerability to introduced pests

As an island nation, New Zealand has unique biological characteristics that have developed in isolation over millions of years. This isolated development has meant New Zealand’s primary production has benefited from a high health status; that is, being relatively free from pests and diseases compared with other countries.

Over the past few decades, increased trade and travel and changing climatic conditions have increased New Zealand’s vulnerability to introduced pests that can affect our land-based economy. An example is the varroa mite, which affects bees and, therefore, pollination activity.

An increasing number of vessels, cargo shipments, and people are arriving from other regions which have organisms with the potential to become high-risk pests for New Zealand’s primary production sectors.

Land management legislation

Resource Management Act 1991

The Resource Management Act 1991 is the primary piece of legislation that governs the use, development, and protection of land in New Zealand. The Resource Management Act promotes the sustainable management of natural and physical resources, including land.

District council functions under the Resource Management Act include the integrated management and control of the effects of the use, development, or protection of land.

Territorial authority functions include controlling the effects of land use relating to natural hazards, hazardous substances, and biodiversity.

Regional council functions include the control of the use of land for purposes of soil conservation, natural hazards, water quality, and hazardous substances.

Both territorial and regional councils have functions relating to identifying, monitoring, and managing the effects of contaminated land.

A number of other Acts impact on land management. These include:

-

Biosecurity Act 1993

-

Building Act 2004

-

Crown Minerals Act 1991

-

Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996

-

Historic Places Act 1993

-

Local Government Act 1974

-

Local Government Act 2002

-

Soil Conservation and Rivers Control Act 1941.

Legislation relating to land tenure includes:

-

Land Act 1948

-

Land Transfer Act 1952

-

Property Law Act 1952

-

Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993.

See chapter 1, ‘Environmental reporting’, for more information on the core set of national environmental indicators and how they are used.

There are four national indicators for land. These indicators provide information on:

-

land cover

-

land use

-

soil health

-

soil intactness of erosion-prone hill country.

Reporting on changes in the land indicators, combined with other more detailed information about land use (such as trends in agricultural production and exotic forestry), will help identify some of the greatest pressures on New Zealand’s land.

Land cover

Land cover is an indicator of the state of our land.

Since 1997, land cover in New Zealand has been mapped periodically from satellite imagery to create the national Land Cover Databases (LCDB) 1 and 2 (see the ‘Ecological classifications’ section in chapter 1, ‘Environmental reporting’). The LCDB maps 43 different land-cover classes.

This chapter reports on the current state of and changes in land cover using LCDB land-cover classes in nine major groupings, as well as other agricultural production data.

Land use

Change in land use is an indicator of pressure on the land, but is not the same as change in land cover. For example, one land cover (for example, pasture) could be used for a number of land uses (for example, sheep, beef, dairy, or deer farming).

Land-use information can also provide information about land-use intensity, such as stocking rates and productivity.

Land-use maps, and estimates from the Agricultural Production Survey and the National Exotic Forest Description, are used in this chapter to report on national changes in land use and land-use intensity.

Soil health

Soil health (or soil quality) is the biological, chemical, and physical condition of different soil types under specific land uses.

The biological health of soil is determined by measuring the level of potentially mineralisable nitrogen in the soil.

The chemical health of soil is determined by measuring the levels of the following chemical compounds or properties of the soil:

-

carbon

-

nitrogen

-

pH

- Olsen phosphate.

The physical health of the soil is determined by measuring macroporosity.

This chapter reports on the health of soils under New Zealand’s major primary production land uses (cropping, pastoral farming, and forestry).

To do so, this chapter draws on the results of a soil health monitoring project (the 500 Soils Project). The 500 Soils Project monitored six key measures of soil quality (see Table 9.2) across New Zealand’s 15 main soil orders (see Figures 9.1 and 9.2 and Table 9.1).

As part of the 500 Soils Project, the six key measures of soil health were monitored across seven major land-use categories (Sparling and Schipper, 2004; Sparling, 2007):

-

arable cropping (for example, grains and fodder crops)

-

mixed cropping (for example, vegetables)

-

drystock pasture

-

dairy pasture

-

tussock grasslands

-

plantation (exotic) forestry

-

native forests.

Table 9.2: Measures of soil health and information these provide

|

Measures |

Soil health information |

|---|---|

|

Biological properties |

|

|

Potentially mineralisable nitrogen |

Readily mineralised nitrogen reserves |

|

Chemical properties |

|

|

Total carbon content |

Organic matter status |

|

Total nitrogen content |

Organic nitrogen reserves |

|

pH |

Acidity or alkalinity |

|

Olsen phosphate |

Plant-available phosphate |

|

Physical properties |

|

|

Macroporosity |

Soil compaction, root environment, aeration |

Data source: Adapted from Sparling and Schipper, 2004; Sparling, 2007.

Soil intactness of erosion-prone hill country

Erosion-prone land is mainly hill country with a slope of more than 21 degrees. The most erosion-prone hill-country lands are in pastoral land cover and have soils that are known as ‘yellow-brown earths’ situated on weakly consolidated mudstones and sandstones.

Land cover can be used to assess the soil intactness of erosion-prone hill country (that is, the ability of soils to stay in place on erosion-prone hill country).

This chapter reports on changes in pasture on erosion-prone hill country around New Zealand. To do so, hill-country pasture is identified from the LCDB, and its erosion potential graded as ‘severe’, ‘very severe’, or ‘extreme’ depending on its slope, the underlying soils, and any limits to land-use capability (land-use capability describes the capacity of land to sustain permanent primary production).

Other forms of soil erosion, such as wind erosion, are not discussed in this chapter.

Land cover

New Zealand’s varying land-cover patterns are the result of human and natural pressures, such as land-use changes and geological and ecosystem processes.

Table 9.3 shows the area of the nine major land-cover classes from the LCDB, including the percentage contribution each class makes to New Zealand’s total land area. The table also illustrates the change within each class for the five-year period between 1997 and 2002.

North and South Island maps showing these same nine land-cover classes for 2002 are presented in chapter 1, ‘Environmental reporting’. Changes in native vegetation since human settlement, between 1997 and 2002, are reported in chapter 12, ‘Biodiversity’.

Table 9.3: Changes in land cover between 1997 (LCDB 1) and 2002 (LCDB 2)

| Land-Cover Class | 1997 Area (Hectares) | Percentage of Total Land Area (%) | 2002 Area (Hectares) | Percentage of Total Land Area (%) | Change in Area (Hectares) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exotic forest | 1,822,300 | 6.79 | 1,961,800 | 7.31 | 139,500 |

| Exotic shrubland | 370,900 | 1.38 | 363,300 | 1.35 | -7,600 |

| Native forest (including mangroves) | 6,485,400 | 24.18 | 6,483,100 | 24.17 | -2,300 |

| Native vegetation | 5,263,400 | 19.62 | 5,248,500 | 19.57 | -14,900 |

| Other native land cover | 1,588,400 | 5.92 | 1,589,100 | 5.92 | 700 |

| Primarily horticulture | 413,000 | 1.54 | 417,400 | 1.56 | 4,500 |

| Primarily pasture - High-producing exotic grassland | 8,985,200 | 33.50 | 8,885,800 | 33.13 | -99,400 |

| Low-producing grassland | 1,678,100 | 6.26 | 1,652,300 | 6.16 | -25,800 |

| Artificial surfaces | 215,000 | 0.80 | 220,500 | 0.82 | 5,500 |

| Total | 26,821,600 | 100 | 26,821,600 | 100 |

Note: Figures rounded to the nearest 100 hectares. Data source: Ministry for the Environment.

Vegetation cover

As shown in Table 9.3, exotic forest covered 7.31 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area in 2002. Between 1997 and 2002, exotic forest increased in area by 139,500 hectares. During this time, native forest (including mangroves), native vegetation, and primarily pasture land-cover classes reduced in area by 142,400 hectares. Over the same period, exotic forests were primarily planted onto pasture with some exotic forest replacing exotic shrubland and, in some cases, native vegetation (mānuka and kānuka).

Table 9.3 also shows that land area in exotic shrubland reduced by 7,600 hectares between 1997 and 2002. Much of this was gorse and broom which may have been converted to forestry land, left to revert to native scrub, or converted into vineyards. (See discussion under ‘Primarily horticulture’ and ‘Primarily pasture’ below.)

Between 1997 and 2002, native forest decreased by 2,300 hectares. In 2002, native forest, native vegetation, and other native land cover made up around 50 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area – just over 13 million hectares. (See chapter 12, ‘Biodiversity’ for more information about changes in native forest, native vegetation, and other native land cover.)

Native vegetation (excluding native forest and other native land cover) reduced in area by 14,900 hectares between 1997 and 2002. This reduction was predominantly due to changes in land area covered by:

-

broadleaved native hardwoods (a reduction of 6,600 hectares)

-

mānuka and kānuka (a reduction of 5,400 hectares)

-

tall tussock grassland (a reduction of 2,500 hectares).

LCDB analysis shows that 83 per cent of the land area in broadleaved native hardwoods was converted into exotic forest land cover and 12.5 per cent was converted into pasture and grassland. Of the mānuka and kānuka, 52.5 per cent was converted into exotic forest land cover, 36 per cent into low-producing grassland, and 10 per cent into high-producing exotic grassland. All tall tussock grassland that experienced land-use change was converted into exotic forest land cover.

Overall, about 65 per cent of the 14,900 hectare reduction in native vegetation was converted into exotic forest land cover, with 7 per cent into high-producing exotic pasture and 17 per cent into low-producing grassland.

Primarily horticulture

Horticultural, viticultural, and cropping land-cover classes made up just under 1.6 per cent (or 417,400 hectares) of New Zealand’s total land area in 2002. This included:

-

58,300 hectares in orchard and other perennial cropland (for example, nuts, berryfruit)

-

25,400 hectares in vineyard

-

333,700 hectares in short rotation cropland (for example, arable cropping such as grains and fodder crops for livestock feed, or market gardens for vegetables).

There was little change between 1997 and 2002 in the land area in orchard and perennial cropland (an increase of 0.39 per cent or 200 hectares) and short rotation cropland (a reduction of 0.37 per cent or 1,200 hectares). However, LCDB analysis shows the land area in vineyards increased by 28 per cent (or 5,500 hectares). Part of this increase was due to conversion of short rotation (arable) cropland.

Primarily pasture

‘Primarily pasture’ classes (high-producing exotic grassland and low-producing grassland) covered just over 39 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area in 2002. There was a reduction in high-producing exotic pasture of 99,400 hectares (or 1.1 per cent) between 1997 and 2002. LCDB analysis shows that some of this land area was converted into urban areas (see ‘Artificial surfaces’ on the following page). Over the same period, the land area in low-producing grassland reduced by 25,800 hectares (or 1.54 per cent), and was mainly converted to exotic forestry.

As a comparison, New Zealand’s Agricultural Production Statistics surveys between 1972 and 1996 show that the land area in grassland including lucerne (that is, pastoral land cover) was about 8.0 million hectares in 1972 and just over 9.1 million hectares in 1996 – an increase of 1,153,992 hectares or about 15 per cent over 24 years. The total land area in pasture increased to just over 9.5 million hectares by 1992, but dropped to 9.4 million hectares by 1994. Over the same 24-year survey period, pasture for dairy farming increased from about 1.4 million hectares to just over 1.9 million hectares or 39 per cent (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, pers comm; Statistics New Zealand, 1972–1996).

Artificial surfaces

Artificial surfaces include urban and built-up areas (towns and cities), landfills and surface mines, transport infrastructure, and urban parkland and open space. Artificial surfaces covered 220,500 hectares (just under 1 per cent) of New Zealand’s total land area in 2002.

Table 9.3 above shows a 2.5 per cent increase, or 5,500 hectares, for artificial surfaces between 1997 and 2002. The land areas in surface mines and landfills, however, reduced over this same period. Built-up areas (human settlements) made up 5,300 hectares or 96 per cent of the 5,500 hectare total, and increased by 3 per cent over the same period.

The increase in built-up areas is mainly occurring on the fringes of cities and towns through rural subdivision. For example, 88 per cent of the 5,300 hectare increase was urban and built-up areas that came from pastoral land, with a further 6 per cent from exotic forest land not replanted. Growing rural towns, such as those in the Waimakariri District in the South Island, illustrate this trend in rural subdivision.

Human settlement in New Zealand increased by just over 3 per cent between 1997 and 2002.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry

Table 9.4: Dominant Land Use and Selected Land Cover in New Zealand, 2004

| Land-Use Classes | Area (ha) | % of Total Land |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy | 1,879,600 | 7.00% |

| Intensive sheep & beef | 3,841,100 | 14.32% |

| Hill-country sheep & beef | 4,023,200 | 15.00% |

| High-country sheep & beef | 48,900 | 0.18% |

| Deer | 249,700 | 0.93% |

| Other animals | 64,900 | 0.24% |

| Ungrazed | 659,800 | 2.46% |

| Urban | 203,600 | 0.76% |

| Planted forest | 1,957,000 | 7.30% |

| Arable crops | 1,200 | 0.0044% |

| Vegetables | 2,200 | 0.0083% |

| Berryfruit | 1,200 | 0.0045% |

| Pipfruit | 10,200 | 0.038% |

| Grapes | 18,800 | 0.070% |

| Summer fruit | 1,800 | 0.0069% |

| Tropical fruit | 1,600 | 0.006% |

| Kiwifruit | 6,400 | 0.024% |

| Flowers | 57 | 0.0002% |

Land-Cover Classes

| Land Cover | Area (ha) | % of Total Land |

|---|---|---|

| Tussock | 2,645,200 | 9.86% |

| Native forest | 6,567,200 | 24.48% |

| Rivers, lakes, snow, ice | 2,094,200 | 7.81% |

| Scrub | 2,543,600 | 9.48% |

Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

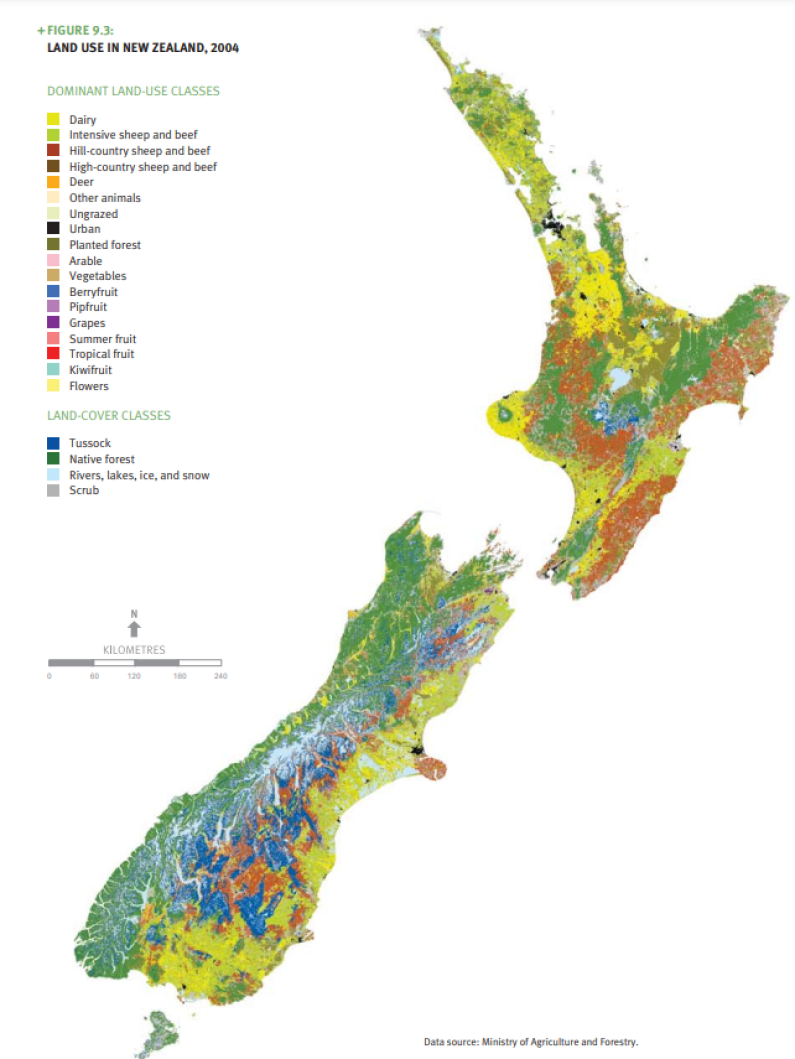

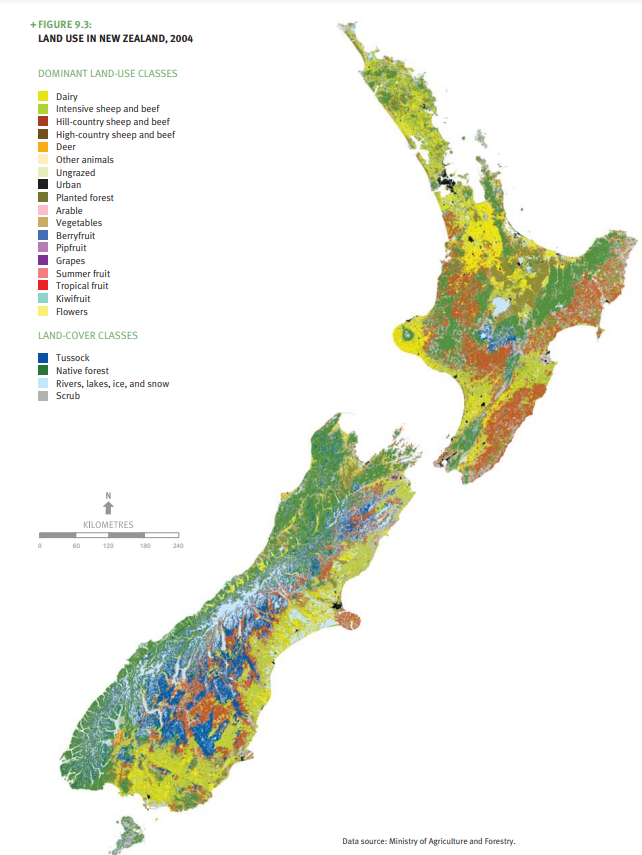

Figure 9.3 and Table 9.4 show that in 2004, pastoral land use (for example, sheep, beef, and dairy farming) was New Zealand’s largest human land use at just over 37 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area. In the same year, natural land cover – such as tussock, native forest, rivers, lakes, snow, ice, and scrub – covered just over 52 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area. Natural land cover is expected to be primarily used for recreation and conservation purposes.

These figures support land cover measurements taken by LCDB satellite in 2002, which recorded that natural land cover was 50 per cent of New Zealand’s total land area that year, with land cover in pasture at 39 per cent.

More about intensive land use

Recent trends in land use in New Zealand include an increase in intensive pastoral land use with higher stocking rates and stocking densities.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation’s Agricultural Production Index 2006 (cited in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007), production rates from pastoral farming increased in New Zealand by 38 per cent between 1990 and 2003. The increase in production is mainly attributable to:

-

more intensive farming (that is, an increase in stocking rates or more livestock numbers per hectare)

-

more productivity per animal (for example, increased milk production per cow, or higher lambing percentages and carcass weights) (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007).

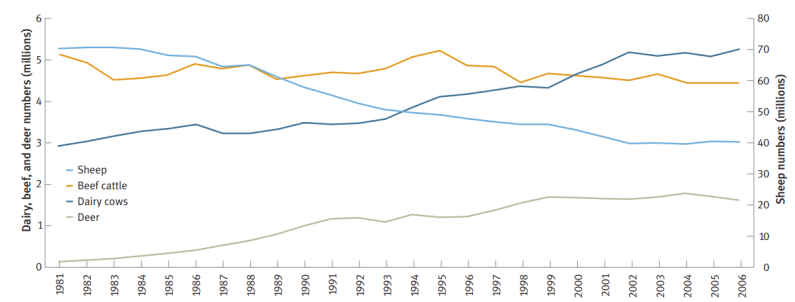

Figure 9.4 shows trends in livestock numbers in New Zealand over the past three decades. Sheep and beef cattle numbers have fallen since the early 1980s, while dairy cow and deer numbers have increased.

While the total area of New Zealand land in pasture has been decreasing since 1972, the area of land in dairy pasture has increased (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, pers comm). Figure 9.4 shows that dairy cow numbers have almost doubled (from 2.92 million in 1981 to 5.22 million by 2006) even though the number of dairy farms has decreased, as shown in Table 9.5. More recent figures indicate that the national dairy herd has grown by 24 per cent between 1996 and 2006.

This intensification of agricultural land use has occurred as farmers have responded to economic signals by converting suitable dry-stock pasture, exotic forestry, and existing dairy farms into more intensive dairy farms.

A change to more intensive farming in some regions has resulted in:

- further reduction of freshwater quality in lowland rivers and waterways

- changes in soil health

- increases in some greenhouse gas emissions (for example, methane).

The intensification of dairy and deer farming has been particularly notable in the South Island. Intensive agriculture is most common in the lowland areas of Northland, Waikato, Taranaki, Manawatū, Canterbury, and Southland.

Table 9.5 shows that dairy farms decreased in number from 16,843 in 1994 to 12,810 in 2005. As the area farmed fell, agricultural productivity increased (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007).

Image: Data source: Ministry for the Environment, 2007a.

Table 9.5 Number of dairy farms in New Zealand, 1994–2005

| Year | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1999 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

North Island |

14,808 |

14,387 |

14,170 |

13,515 |

11,928 |

10,791 |

10,707 |

10,362 |

|

South Island |

2,035 |

2,134 |

2,296 |

2,436 |

2,424 |

2,160 |

2,280 |

2,448 |

|

Total New Zealand |

16,843 |

16,521 |

16,466 |

15,951 |

14,352 |

12,951 |

12,987 |

12,810 |

Note: No Agricultural Production Survey was conducted for 1997, 1998, or 2001. In 2000, the survey related only to horticulture. Farm counts have been based on New Zealand Standard Industrial Classifications.

Data source: Statistics New Zealand.

The intensification of pastoral land use has led to a noticeable increase in the use of fertilisers and irrigation in high-producing exotic pastures, both of which have increased the environmental pressures on our waterways and groundwater (see chapter 10, Freshwater).

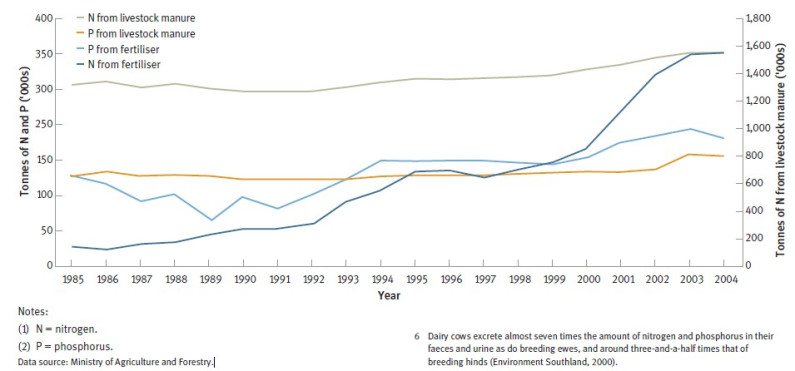

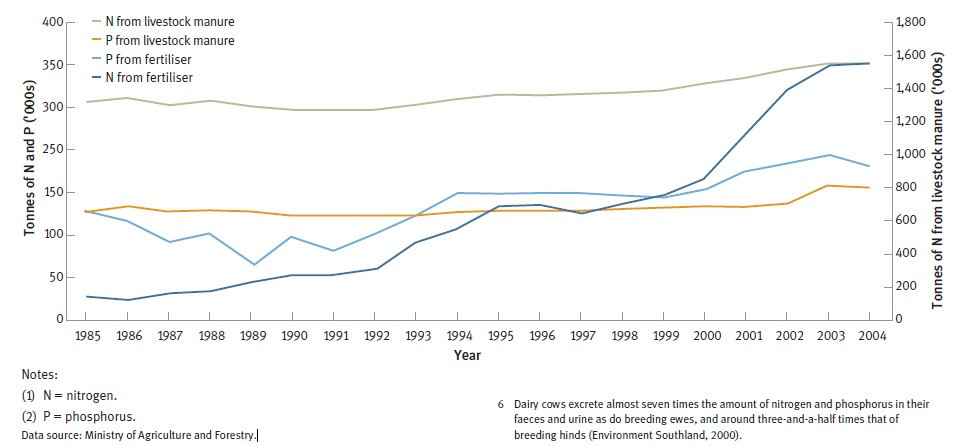

Figure 9.5 shows the change in nitrogen and phosphorus inputs to agricultural catchments since the mid-1980s. The amount of nitrogen fertiliser used in New Zealand has increased by about 10 times since 1985 and doubled since the mid-1990s. This is in line with the findings of a 2004 report on agriculture in New Zealand. The report found that the use of synthetic fertilisers based on fossil fuels on dairy farms had increased in recent decades. This doubled energy inputs into the average New Zealand dairy farm over the past 20 years, mostly due to the increase in nitrogen fertiliser usage (Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 2004).

Nitrogen from livestock manure, which contributes around five times the amount of nitrogen to the land as nitrogenous fertilisers, has also steadily increased. This increase is consistent with the recent trend towards more intensive forms of farming in New Zealand; particularly dairy farming. The high density of grazing stock on dairy farms delivers more nutrients 6 to the land than other forms of farming.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

LOCAL ACTION for sustainable land management

Increasingly, farmers are taking collective action to achieve sustainable land use. Over 250 land-care or community-based groups have formed throughout the country to address local land-management issues. Projects these groups are working on include:

-

land and water monitoring

-

pest and weed control

-

revegetation and research into alternative land management techniques.

Many projects are worked on in partnership with local authorities and research agencies. Federated Farmers, farm discussion groups, and producer boards are also working on a variety of issues related to sustainable land care.

While some of these issues are significant to New Zealand as a whole, the decision rests with individual farmers as to how they respond to the challenge of changing to more sustainable land-use practices.

The nature and scale of land management issues vary from farm to farm. Some can be dealt with by an individual farmer using existing information. Other issues, for example, poor water quality, will require a partnership of some kind, such as neighbours working together, or a group of farmers working with a researcher and a local authority.

New Zealand Landcare Trust

The New Zealand Landcare Trust was established in 1996. Currently more than 250 landcare groups operate around New Zealand with the vision of promoting sustainable land management. Each group’s level of activity depends on the community in which they are based and the specific issues they are trying to address. Landcare groups are particularly active where regional councils have programmes for biodiversity protection and offer incentives or assistance to landholders.

New Zealand Farm Forestry Association

The New Zealand Farm Forestry Association (NZFFA) was formed in 1957. Membership is spread over 29 branches throughout New Zealand. NZFFA estimates their members own or manage up to 100,000 hectares of forest, and influence the management of a similar area. These forests consist of radiata pine, cypresses, eucalypts, douglas fir, blackwoods, poplars, and other hardwoods, as well as native species. Around 800 members will each harvest, on average, 12.7 hectares of plantation forest over the next five years. NZFFA provides a forum for members to share advice with one another on farm forestry.

Diversification of land use

The last decade has seen the diversification of many land-use activities in New Zealand. This diversification is particularly evident in the horticultural industry – changing land use to viticulture is just one example. In both 1997 and 2002, horticulture, including vineyards, orchards, and perennial crops, covered just under 1.6 per cent of our land. However, the area of vineyards grew by 28 per cent over the same period, illustrating the changing face of horticultural land. Horticultural land use has also diversified in other ways. Over the past 20 years, in response to niche market demand, certification schemes have enabled the development of organic land use, such as dairy, vegetable, and meat products.

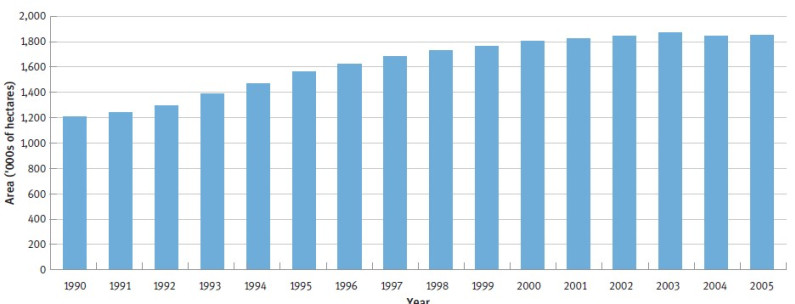

Exotic forestry land use

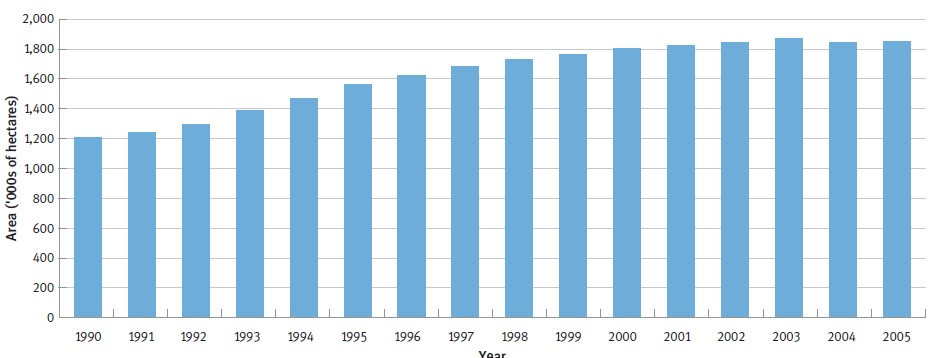

The last decade has also seen a decrease in activity in the forestry sector resulting in reductions in new exotic forest plantings and replantings following harvesting. In April 2006, planted forests were estimated to cover 1.8 million hectares of New Zealand’s total land area (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007a). Figure 9.6 shows the estimated total area of exotic forest land cover from 1990 to 2005. It illustrates that while the total land area in exotic forestry in New Zealand between 1991 and 2005 remained higher than that in 1990, the trend of increasing land area in exotic forestry peaked in 2003, and the total land area in exotic forestry has begun to decline since that time.

Over the past 10 years, greater diversification of land use has been evident in New Zealand.

Source: Courtesy of Devcich Design.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

Exotic forestry land use is monitored for new plantings and for replantings of harvested plantations.

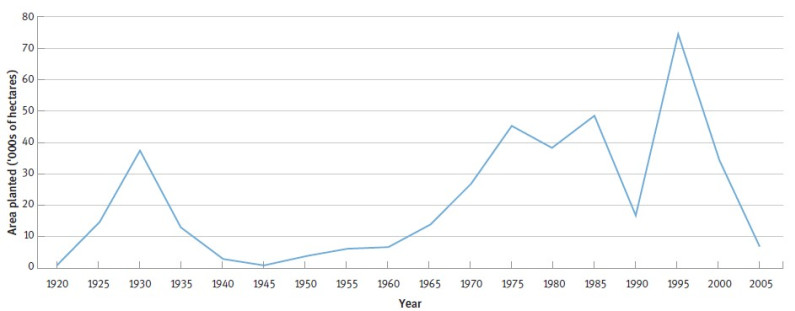

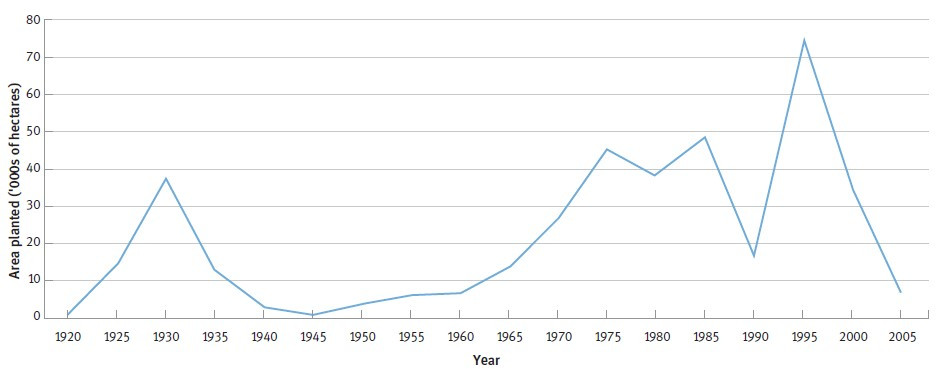

In the period 1992 to 1998, new area planting rates were high – averaging 69,000 hectares per year (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007a). Since 1998, the rate of new forest plantings has declined. In 2005, only 5,000 hectares were planted – the lowest level since 1959 (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007a). Figure 9.7 shows the change in the total area of new forest plantings from 1920 to 2005.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

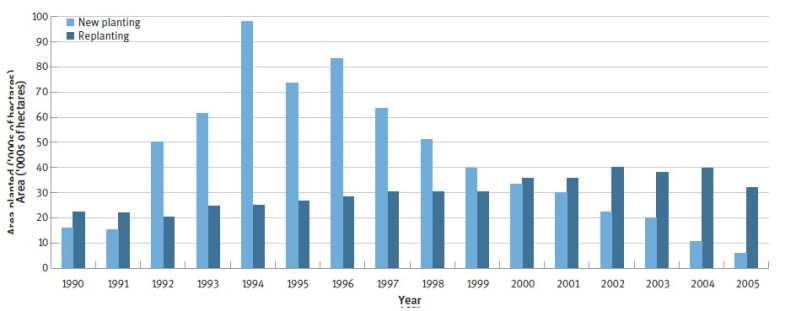

Figure 9.8 shows the trends in new plantings and replantings of exotic forestry between 1990 and 2005. The reduction in new plantings since the mid-1990s means that New Zealand’s land area in exotic (commercially planted) forest is no longer increasing (as shown in Figure 9.6). The maintenance of the current area of exotic forestry land will depend on replanting trends, that is, whether forestry land use is maintained after harvest.

Historically, most commercially planted forest was replanted after harvest. However, in 2004, a new trend of not replanting forest after harvesting started to become apparent. In a few cases immature forest has been converted to pasture. The 2006 National Exotic Forest Description survey indicates that approximately 12,900 hectares of forest (33 per cent of the total area harvested) will not be replanted after clear-felling (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007a). This compares with a historical average of 2 to 5 per cent of exotic forests not being replanted after harvesting (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2007a).

Image: Data source: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

If low replanting rates continue, New Zealand’s total exotic (production) forest land area will continue to decline. A reduction in total exotic forest land area will have implications for the sequestration of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas (see chapter 8, ‘Atmosphere’). It may also affect flood management, nutrients and soil health, soil erosion, and ecosystem processes related to the displacement of species living in exotic forest habitats. The impacts of deforestation on the environment will largely depend on the land use that is replacing forestry, how that land use is managed, and the management of the surrounding catchment.

Soil health

Seventeen per cent of New Zealand’s gross domestic product depends on the top 15 centimetres of our soil (Sustainable Land Use Research Inititative, no date). Soils underpin food and fibre production in New Zealand and protect our environment by:

-

acting as buffers and filters to reduce nutrient loss

-

limiting the need for irrigation

-

breaking down pollutants

-

regulating greenhouse gas emissions

-

acting as a fundamental part of the water cycle.

Monitoring under the 500 Soils Project (and subsequent regional council programmes) shows there have been changes over time to the health of New Zealand soils. Results of monitoring show:

-

widespread moderate compaction under pastures and some cropping land uses

-

a loss of organic matter and soil structural stability under cropping

-

nitrogen build-up under some dairy pastures, coupled with high levels of available phosphate (Sparling, 2007).

Table 9.6 shows the soil health variables used to assess the biological, chemical, and physical state of New Zealand’s soils nationally for seven major land-use types (arable cropping, mixed cropping, drystock pasture, dairy pasture, tussock grasslands, exotic forestry, and native forests) monitored across New Zealand’s 15 soil orders. Monitoring New Zealand’s soils by major land-use types and soil orders helps us to better understand how different soils respond to land-use pressures.

Table 9.6: Soil properties under the 500 Soils Project, arranged by land-use categories

| SOIL PROPERTY | ARABLE CROPPING (N=44) | MIXED CROPPING (N=17) | DRYSTOCK PASTURE (N=142) | DAIRY PASTURE (N=127) | TUSSOCK GRASSLANDS (N=20) | EXOTIC FORESTRY (N=67) | NATIVE FORESTS (N=58) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mineralisable nitrogen (µg/cm³) | 56 | 70 | 128 | 160 | 88 | 63 | 100 |

| Total carbon (mg/cm³) | 40.7 | 37.6 | 50.8 | 66.9 | 38.3 | 46.4 | 56.5 |

| Total nitrogen (mg/cm³) | 2.32 | 3.13 | 4.29 | 5.92 | 2.62 | 2.99 | 3.48 |

| pH in water | 6.17 | 6.17 | 5.75 | 5.74 | 5.61 | 5.36 | 5.36 |

| Olsen phosphate (µg/cm³) | 49 | 44 | 19 | 44 | 16 | 10 | 11 |

| Macroporosity (%v/v) | 14.7 | 9.3 | 13.3 | 10.1 | 15.6 | 25.6 | 9.3 |

Notes:

(1) The number of soil sites is indicated by ‘N’.

(2) μg/cm3 = micrograms per cubic centimetre.

(3) mg/cm3 = milligrams per cubic centimetre.

Source: Sparling and Schipper, 2004.

Because pasture lands are so widespread in New Zealand, the condition of pasture soils has a major bearing on soil health nationally. Most declines in soil health are potentially reversible, but the shift towards more intensive farming practices in many regions around New Zealand may make a reversal difficult to achieve for some soils.

Chemical and biological soil health

Organic matter

As Table 9.6 shows, total organic carbon (a measure of soil organic matter) was lowest on cropping land and on tussock grasslands. Arable and mixed cropland soils often have lower organic matter than soils under pasture because the cropland soil is regularly cultivated.

On a national scale, horticulture in New Zealand, including vineyards, orchards, and perennial crops, covers 1.6 per cent of the total land area, compared with 24 per cent in Europe, making environmental effects from cropping in New Zealand comparatively localised.

Because tussock grassland grows on drier soils, they are naturally low in organic carbon. Drier soils build up organic matter very slowly because the growing conditions result in lower productivity.

Monitored pasture topsoils all had high levels of organic matter in the top 10 centimetres of the soil (total carbon, total nitrogen, and mineralisable nitrogen). This result was found to be similar or greater than organic matter levels under long-standing native vegetation. However, evidence in the soil profile down to 0.5 metres shows that over the past 25 years organic matter losses have occurred on intensively farmed pastures (Sparling, 2007).

Nitrogen and phosphorus

As Table 9.6 shows, both total nitrogen and mineralisable nitrogen were greater under pastures than under other land uses. While a supply of mineralised nitrogen is essential for pasture productivity, there is a risk that when supply exceeds demand (when saturation is reached) any excess soluble nitrogen can be leached from the soil and adversely affect water quality (see chapter 10, ‘Freshwater’). Excess soluble nitrogen is of particular concern given the high proportion of New Zealand land area in pasture.

The monitored dairy pastures and cropland soils exhibited high Olsen phosphate results (plant-available phosphate). This result reflects the regular application of superphosphate to New Zealand soils to stimulate the growth of introduced grasses, clovers, and arable crops.

Monitoring suggests continued soil compaction in pastures (macroporosity of less than 10 per cent) along with increased (possibly excess) levels of phosphate and nitrogen are likely to continue. Overall, results from soil health monitoring may indicate that storage of nitrogen in organic forms, particularly in dairy pasture topsoils, is nearing saturation point.

Acidity

Soil pH (acidity or alkalinity) under exotic forests was found to be similar to that under native forests. Other agricultural land uses exhibit higher pH values (that is, they are more alkaline). Higher pH values under agricultural land reflect the widespread topdressing of lime following the clearance of forest land cover and the change in land use to more intensive pastoral farming.

Physical soil health

Macroporosity

Moderate soil compaction (low macroporosity) was found on a large proportion of monitored pasture soils. Soil compaction is caused by farm animals treading on pastures, and vehicle traffic and cultivation on croplands.

Macroporosity below a 10 per cent threshold has been shown to adversely affect pasture production. About half the monitored sites under dairy land use were below this desirable threshold. Mixed cropping soils also had low macroporosity.

Maintaining healthy soils

Maintaining healthy soils is fundamental to sustainable land use. See box ‘More about maintaining healthy soils’, which outlines:

-

why healthy soils are important

-

what happens when soil health is compromised.

More about maintaining healthy soils

Soil forms a thin skin of mineral and organic matter on the earth’s surface and maintains the ecosystems on which we depend. The soil resource is non-renewable in a human lifespan (Doran et al, 1996). Monitoring soil health identifies whether soils are degraded and the factors that contribute to degraded soils. The results of this monitoring provide the opportunity to evaluate and redesign land management systems for sustainability.

Degraded soil can result from:

-

soil compaction

-

reduced organic matter

-

an imbalance in soil nutrient status

-

a mismatch between soil pH in relation to land use

-

changes to the biological, chemical, and physical characteristics of a particular soil order.

Soil compaction

Soil compaction reduces pasture growth and, when coupled with high-surface soil fertility (that is, high availability of soil nutrients), increases the risk of phosphates and nitrogen reaching streams and lakes through greater surface run-off.

Organic matter

The terms ‘soil organic matter’ and ‘soil organic carbon’ are used interchangeably. Total (organic) carbon is a measure of soil organic matter. When measured over time, the rate of soil organic matter turnover (total carbon content) provides information about soil health, for example:

-

the loss of soil biological activity (animal and plant communities in the soil such as worms and fungi)

-

soil nutrient depletion

-

changes in water infiltration and storage potential.

Soil nutrients

Soil nutrients are essential for plant growth and for maintaining soil health. Levels of nutrients may be affected by the excessive build-up of soil nutrients (from high stocking rates, imported feed high in nitrogen, or use of nitrogen fertiliser) or their removal. When excess nutrients are flushed through the soil by water flow, they can cause imbalances in the soil system or surrounding environment. For example, the excessive use of nitrogenous fertilisers may result in a build-up of nitrates in groundwater and rivers.

In the reverse situation, the mining of soil nutrients can also create a problem. Removing vegetation or animal products from the land can result in loss of soil nutrients. Cultivation and vegetation burn-off can also reduce soil fertility. Soil nutrients can be replaced by returning organic matter to the soil, using fertiliser, and using nitrogen-fixing pasture plants (such as clovers).

Soil acidity

Soil acidity is relevant to the nutrient management and biological function of soils. Soil acidification affects plant productivity. Acidification occurs naturally in soils but it can be accelerated by different land uses. For example, the application of fertilisers that contain ammonium or elemental sulphur can lead to acidification, as can the removal of soil nutrients (through cropping and nitrate leaching). Acidity can be manipulated with the addition of lime. In general, as soils become more acidic, their ability to support most kinds of vegetation is reduced.

Soil intactness of erosion-prone hill country

Soil intactness (the ability of soils to stay in place) on erosion-prone hill country is important for three main reasons.

-

Soil loss (through actions of water or wind erosion) accelerates sedimentation and nutrient run-off, and degrades water quality in adjacent or downstream water bodies.

-

Downstream erosion debris causes rivers to become filled in with silts and gravels, increasing the risk of flooding in heavy rainfall.

-

The gradual loss of topsoil affects the general health of the soil and reduces the fertility and productive capacity of the soil resource – the restoration of which may take hundreds of years (under natural conditions a centimetre of topsoil takes 100 to 400 years to build) (Doran, 1996).

Resource and policy managers are primarily concerned with soil erosion caused by human activity (induced erosion), rather than natural erosion processes. Soil erosion caused by human activity has been accelerated in many hill-country areas of New Zealand because of a mismatch between land cover and land use. Where pasture covers soft erodible soils, there is no appropriate vegetation to hold the soils in place.

Soil slip erosion on hill-country pasture.

Source: Ministry for the Environment.

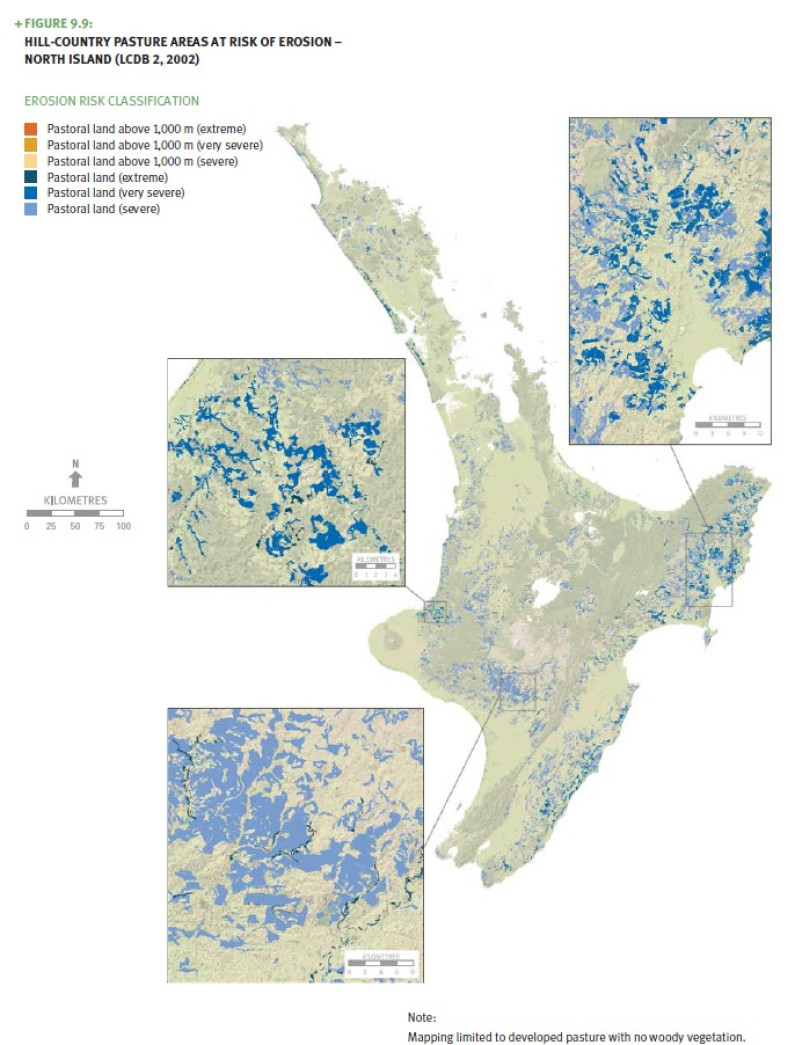

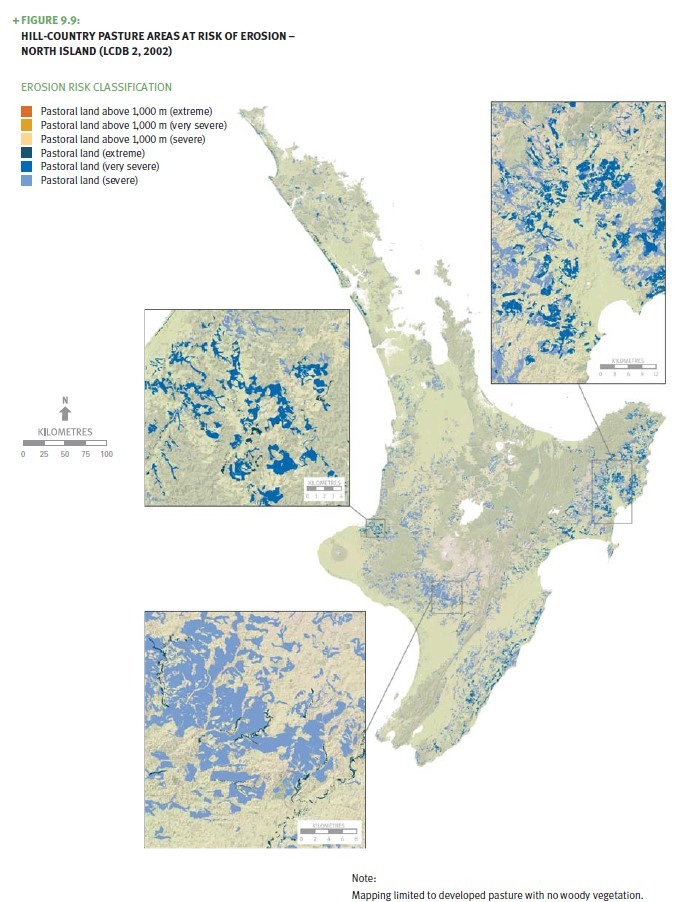

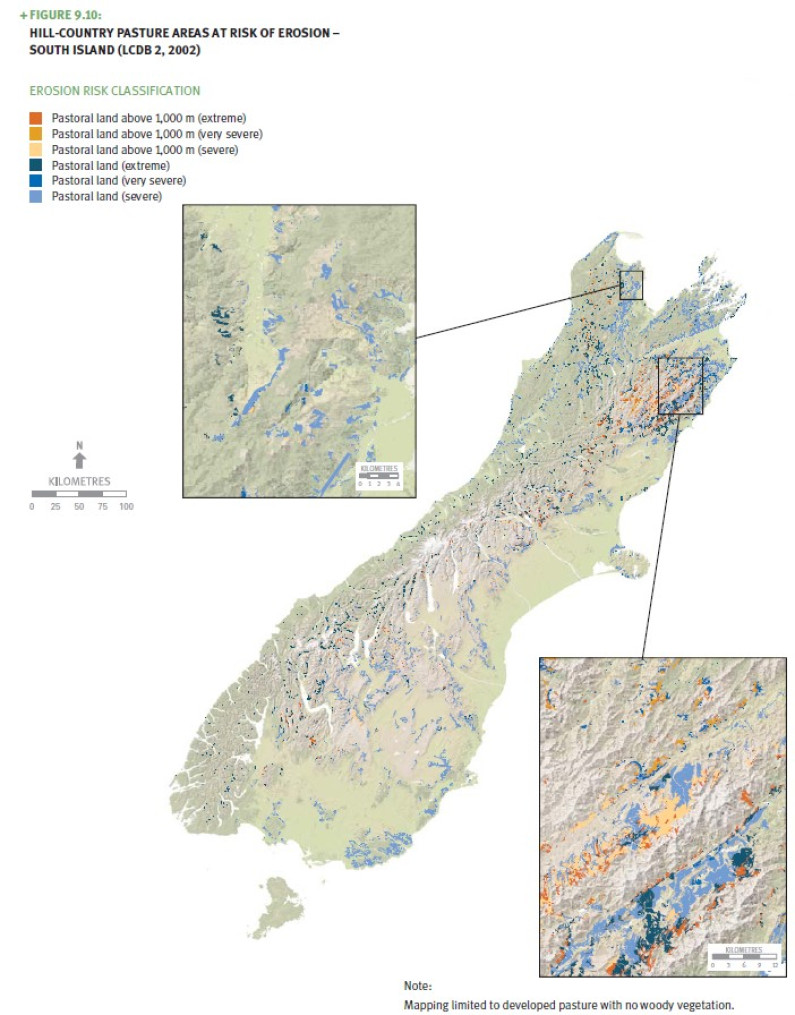

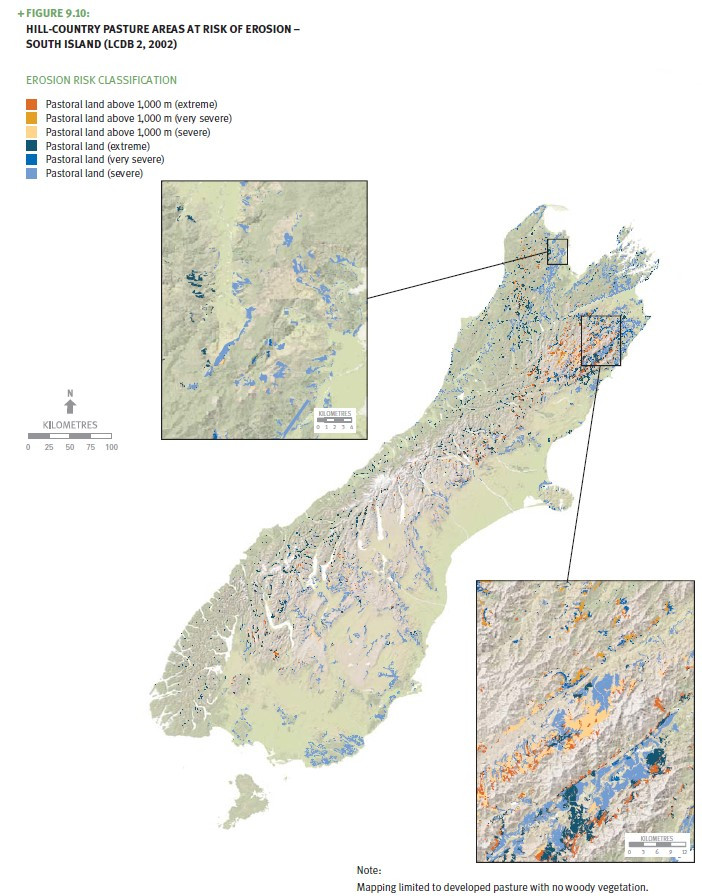

Figures 9.9 and 9.10 show hill-country areas in pasture that are at risk of soil erosion. The measure of risk is based on information from the Land Cover Database and the Land-Use Capability survey classes from the New Zealand Land Resource Inventory (NZLRI). The NZLRI is a national database and inventory of land-use capability classes according to five major physical factors that control productive land uses: geology, soils, relief (slope), erosion potential, and vegetation cover.

Tussock grasslands (high-country sheep and beef areas) are not included in this analysis.

Erosion risk is classified by degree: severe, very severe, or extreme. This classification is based on:

-

soils and underlying geology – areas with yellow-brown earths situated on weakly consolidated mudstones and sandstones pose greater erosion risk

-

slope or altitude – areas with more than 21 degrees or that are 1,000 metres above sea level pose greater erosion risk

-

land cover – whether erosion-prone areas are in pasture or other more appropriate vegetation to hold the soils in place.

Figures 9.9 and 9.10 can be compared with Figures 9.1 and 9.2 (soil order maps), Table 9.1 (soil orders and land uses), and Figure 9.3 (land-use map identifying hill-country sheep and beef areas for 2004).

New Zealand’s geological and land-use histories have worsened hill-country erosion. See box ‘More about hill-country erosion and our geological history’.

More about hill-country erosion and our geological history

New Zealand’s land management problems are compounded by its unique geological history. Much of our land is mountainous and still undergoing uplift. Many land slopes are close to the maximum for pastoral farming. Thirty per cent of our land is hilly with a slope of more than 25 degrees (Sparling, 2007). Many areas are underlaid by soft, erodible materials. About 10 per cent of New Zealand is classed as severely erodible. The removal of native forest between the 1880s and 1920s for pastoral land use increased erosion rates.

All these factors mean that many parts of the country are prone to mass movement soil erosion (that is, extreme landslip, tunnel gully, gully, and earth-flow forms of soil erosion). The loss of soil through erosion, and transport by rivers to the sea, was estimated in 1996 to be 400 million tonnes a year (Ministry for the Environment, 1996).

Earth flows, soil slips, and gully formations seriously impair the viability and productivity of farms in erosion-prone areas. After hill-country slip erosion, for example, pasture production takes approximately 20 years to recover to within 70 to 80 per cent of its pre-erosion levels (Ministry for the Environment, 1996). Downstream, erosion debris causes rivers to become filled in with silts and gravels, with the consequential increased risk of flooding. Erosion can also contribute to water quality problems such as loss of aquatic habitat and increased sediment loads.

New Zealand’s soil erosion problem on the East Coast of the North Island is unique in that the magnitude of the problem is far greater than elsewhere in New Zealand. The Gisborne region comprises 7.8 per cent of the North Island and 26 per cent of the country’s severely erodible land. The impacts of erosion (flooding and sedimentation) in the Gisborne region are considered greater than in other areas of New Zealand, particularly for the southern part of the region, the Waipoa catchment.

Other regions that have erosion-prone hill country include Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Hawke’s Bay, Taranaki, Manawatū–Wanganui, Wellington, Tasman, and Marlborough.

Image: Data source: Landcare Research.

Image: Data source: Landcare Research.

Image: Data source: Landcare Research.

Image: Data source: Landcare Research.

Monitoring of erosion-prone hill country includes measuring changes in land cover from pastoral vegetation. Table 9.7 shows the satellite measurements of land-cover change for areas at risk of erosion in 1997 and how many hectares of pasture in these areas underwent a land-cover change by 2002.

While the percentage change from pasture is small, the results do show a reduction of just over 36,000 hectares nationally between the two periods of land-cover monitoring. Just over half of this total was in the Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay, and Manawatū–Wanganui regions (17,481 hectares in total). In the South Island, the Marlborough and Tasman regions experienced a combined pastoral land-cover change of 4,119 hectares.

LCDB analysis shows that of the 36,400-hectare reduction in pasture on erosion-prone hill country, 36,300 hectares were converted to exotic forestry or retired and left to revert to scrub.

The changes in the land area under pastoral land cover highlight efforts to replace pasture with more stabilising vegetation on erosion-prone hill country. For example, planting bare land in trees has a noticeable impact on erosion rates. In four to five years, the tree roots will have intertwined, the tree foliage will intercept the strike of heavy rainfall, and the soil will begin to be protected. This process is complete when the tree canopy closes.

A number of programmes and initiatives have been set up to help promote sustainable land management, including afforestation of hill-country pasture on erosion-prone land. See box ‘Government action on sustainable land management’.

Table 9.7: Area (in hectares) of pasture on hill-country erosion-prone land by region between 1997 (LCDB 1) and 2002 (LCDB 2)

| Region | Erosion-prone area (hectares) in pasture (LCDB 1) | Erosion-prone area (hectares) in pasture (LCDB 2) | Percentage of total New Zealand land area (LCDB 2) | Percentage of total regional land area (%) | Area (hectares) change from pasture (LCDB 2) | Percentage change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northland | 67,723 | 65,832 | 0.25 | 5.10 | -1,691 | -2.50 |

| Auckland | 13,101 | 12,988 | 0.05 | 2.49 | -53 | -0.40 |

| Bay of Plenty | 27,000 | 24,855 | 0.10 | 2.10 | -1,145 | -4.00 |

| Waikato | 116,049 | 112,315 | 0.42 | 4.58 | -3,680 | -3.17 |

| Gisborne | 167,141 | 158,382 | 0.59 | 19.01 | -8,151 | -4.88 |

| Hawke's Bay | 113,428 | 104,678 | 0.39 | 8.20 | -8,750 | -7.71 |

| Manawatū | 230,585 | 223,535 | 0.83 | 10.84 | -6,693 | -2.95 |

| Taranaki | 40,580 | 38,444 | 0.14 | 5.30 | -2,136 | -5.26 |

| Wellington | 51,608 | 48,378 | 0.18 | 6.10 | -3,230 | -6.25 |

| Nelson | 11,949 | 11,694 | 0.04 | 8.40 | -255 | -2.13 |

| Tasman | 24,249 | 22,697 | 0.09 | 2.39 | -1,552 | -6.40 |

| Marlborough | 14,492 | 13,696 | 0.05 | 2.33 | -796 | -5.49 |

| Canterbury | 113,995 | 113,770 | 0.42 | 2.52 | -220 | -0.19 |

| West Coast | 4,592 | 4,592 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Otago | 101,151 | 101,215 | 0.38 | 3.17 | 64 | 0.06 |

| Southland | 26,083 | 25,437 | 0.09 | 0.80 | -646 | -2.48 |

| North Island | 829,587 | 799,154 | 2.98 | na | –30,433 | –3.67 |

| South Island | 347,134 | 341,213 | 1.27 | na | –5,921 | –1.71 |

| Total | 1,176,721 | 1,140,367 | 4.25 | na | -36,354 | -3.09 |

Notes: (1) Figures rounded to the nearest 100 hectares. (2) Pasture classes from the erosion risk data used for this analysis limited to the LCDB Database ‘Primarily Pastoral’ classes for reporting. Data source: Landcare Research.

GOVERNMENT ACTION on sustainable land management

Plan of Action for Sustainable Land Management and Climate Change

In 2006, a discussion document, Sustainable Land Management and Climate Change: Options for a Plan of Action, was released for public consultation. $170 million has been committed between 2007–2012 to develop and deliver the plan of action, which includes:

-

A five-year adaptation programme that will help the land management sector build the capability to address the risks and opportunities from climate change. As part of this programme a $5.7 million community irrigation fund will be established to help rural communities adapt to increasing drought risk.

-

A range of complementary measures to the Emissions Trading Scheme, including the establishment of farm-scale greenhouse gas monitoring and reporting, and a $50 million Afforestation Grant Scheme that allows landowners who elect not to enter the Emissions Trading Scheme to realise the climate change benefits of afforestation.

-

A five-year work programme aimed at addressing barriers that hinder the private sector capitalising on climate change opportunities. This includes the development of a greenhouse gas footprint response for the primary sector and reviewing market opportunities such as the creation of markets for emission-reducing technologies.

-

A strategic framework for research and technology to underpin the plan of action and coordinate the investment of $10 million per annum by 2010 in new research funding to better enable the agricultural and forestry sectors to reduce their emissions and adapt to climate change This will build on the work of the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium discussed in Chapter 8, ‘Atmosphere’.

-

A Technology Transfer work programme to enhance the ability of the sector to quickly roll out and adapt to new technology.

Sustainable Land Management Programme

The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry leads government initiatives to achieve sustainable land management. The Ministry’s Sustainable Land Management Programme:

-

makes sound science and good information available to support land-management decisions

-

provides regulatory support through various local and national regulatory tools

-

helps establish partnerships for long-term sustainable land-use solutions

-

builds knowledge and capacity in both central and local government.

As part of this programme, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has completed a Sustainable Land Management Framework. The framework guides:

-

government funding for local sustainable land management

-

assessment of the quality and effectiveness of initiatives under the Sustainable Land Management Fund.

Sustainable Land Management Fund