Theme 4: How we use our freshwater and marine resources

Natural resources are essential for our modern way of life and we use them in an astounding number of ways. Some resources regenerate naturally but others, like fossil fuels, are not easily replaced. If we take too much from the environment, the use of a resource becomes unsustainable. This can affect natural systems and deny future generations the same opportunities and benefits from nature that we enjoy today.

Image: Nature’s Pic Images

This theme examines two activities where our use of a natural resource is affecting how the environment functions, and changing our relationship with it:

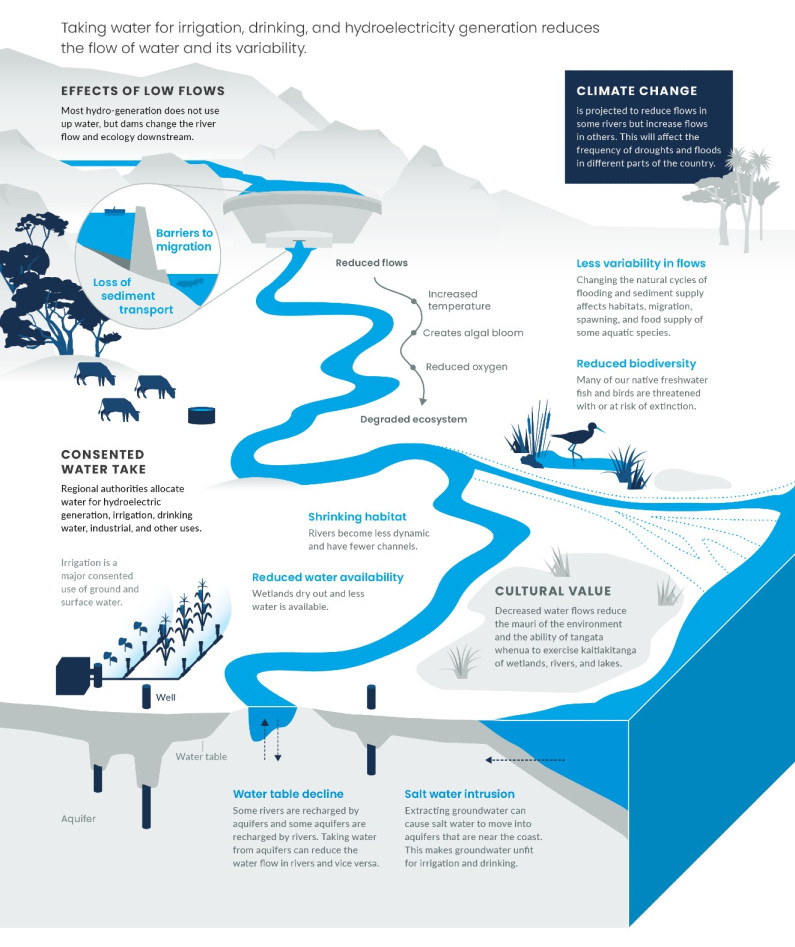

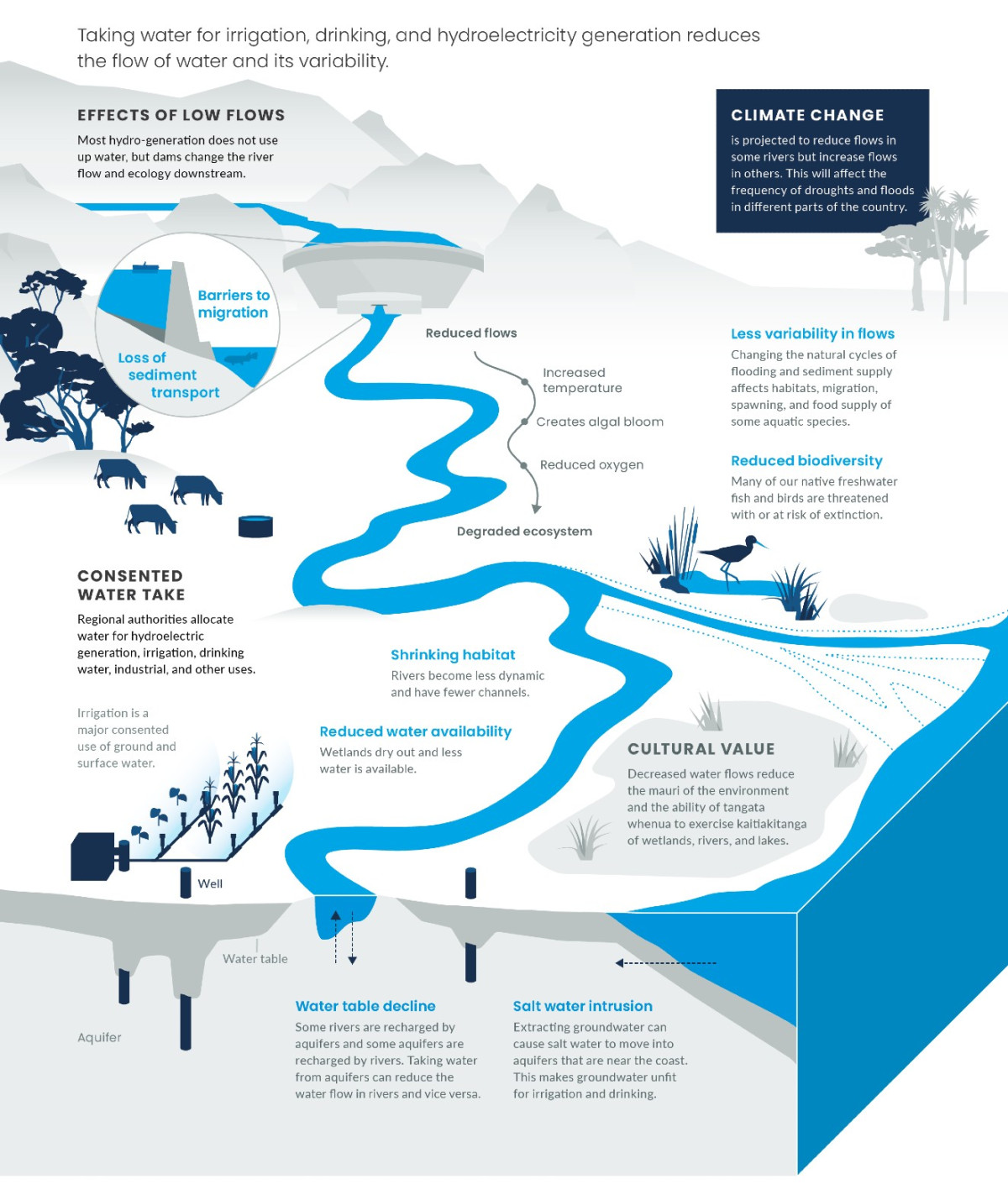

Using freshwater for hydroelectric generation, irrigation, domestic, and other purposes changes the water flows in rivers and aquifers. This affects freshwater ecosystems and the ways we relate to and use our waterways.

The use of freshwater supports our economy and way of life. We rely on surface water and groundwater (taken from aquifers) for drinking, domestic, and industrial uses, and irrigation from these sources is vital for farming. Although New Zealand has plenty of fresh water, we are also heavy users. In 2014, New Zealand's consented water allocation per person was 2,162 cubic metres.

Consents (permits) to take water are managed by regional authorities, which allocate water for particular uses. Individual consents to take water have specified conditions, such as how much water can be taken, from where, at what rate, and at what times.

Nationally, aside from hydroelectricity (which generally doesn’t consume water but does alter river flows), most of the consented water allocation was for irrigation (51 percent in the 2013/14 year). Household consumption made up 14 percent, and industrial use made up 13 percent. Taking water for irrigation happens nationwide but on a large scale mainly in Canterbury and Otago. About 100 hydropower sites nationwide provided 55–60 percent of our electricity in 2017, lessening our dependence on fossil fuels.

The demand for freshwater for irrigation has increased markedly. This has been driven by a near doubling of New Zealand’s irrigated agricultural land area between 2002 and 2017, most notably in Canterbury. This reflects a nationwide shift from sheep and beef farming to dairy farming, and an increase in the number of animals per hectare in some parts of the country (see Issue 4).

The consequences of taking water are mainly related to changes in river flows. Low river flows reduce the habitat for freshwater fish and other species that provide food for other species and for people. Native fish such as the taonga whitebait species inanga and tuna (eels) are vulnerable because they need to move between the sea and fresh water during their lifecycle and dams and culverts can block these migration. Taking water can also reduce the flows and number of channels in braided rivers, which affects some threatened birds like wrybill and kakī.

With reduced or less variable flows, the temperature and the concentration of nutrients and pathogens in a waterway can also increase and make them more susceptible to algal blooms. These changes can degrade freshwater ecosystems and make waterways unfit for recreational and cultural uses.

Read the long description for Effects of taking water

Taking water for irrigation, drinking, and hydroelectricity generation reduces the flow of water and its variability.

Effects of low flows

Less variability in flows

Reduced biodiversity

Shrinking habitat

Reduced water availability

Water table decline

Salt water intrusion

Consented water take

Cultural value

Harvesting marine species affects the health of the marine environment and its social, cultural, and economic value to us. Fishing could change the relationship that future generations have with the sea and how they use its resources.

As befitting an island country, many New Zealanders have a strong connection to the sea. For many, that connection is through fishing – for employment, enjoyment, or cultural connections.

Commercial fishing and the pressures associated with it have reduced in the last decade, and most (97 percent) commercially caught fish come from stocks that are considered to be managed sustainably. In 2017 16 percent of routinely assessed stocks were overfished and 10 stocks are considered collapsed.

Animals that are caught unintentionally are called bycatch. Bycatch of protected species like Hector’s and Māui dolphins, fur seals, sea lions, and seabirds has reduced, but still has a serious effect because many of these species are already threatened.

Trawling the sea floor with large nets or dredges to catch fish and species like scallops and oysters are the most destructive fishing methods and cause damage to the seabed. The area trawled and the number of tows have decreased over the past 15 to 20 years, but still cover a large area, and some areas have been trawled every year for the past 27 years. Between 1990 and 2016 trawling occurred over approximately 28 percent of the seabed where the water depth was less than 200 meters, and 40 percent where depth was 200–400 meters.

Fishing vessels are now larger and more powerful, and use wider trawls and longer lines than when trawling first started more than 100 years ago. A small number of boats today can have the same impact as a larger fleet would have had in previous decades.

Past activities, like hunting seals, are still having an effect on marine mammals, seabirds, and other species. Some species, particularly those with long lifespans or low fertility, recover slowly from disturbance.

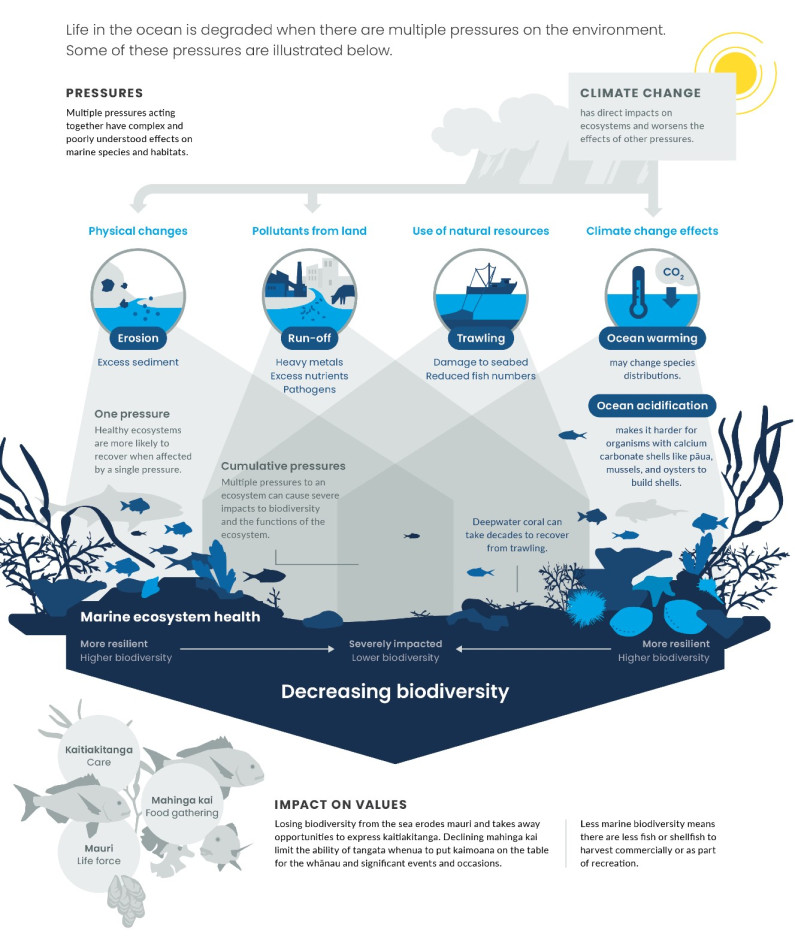

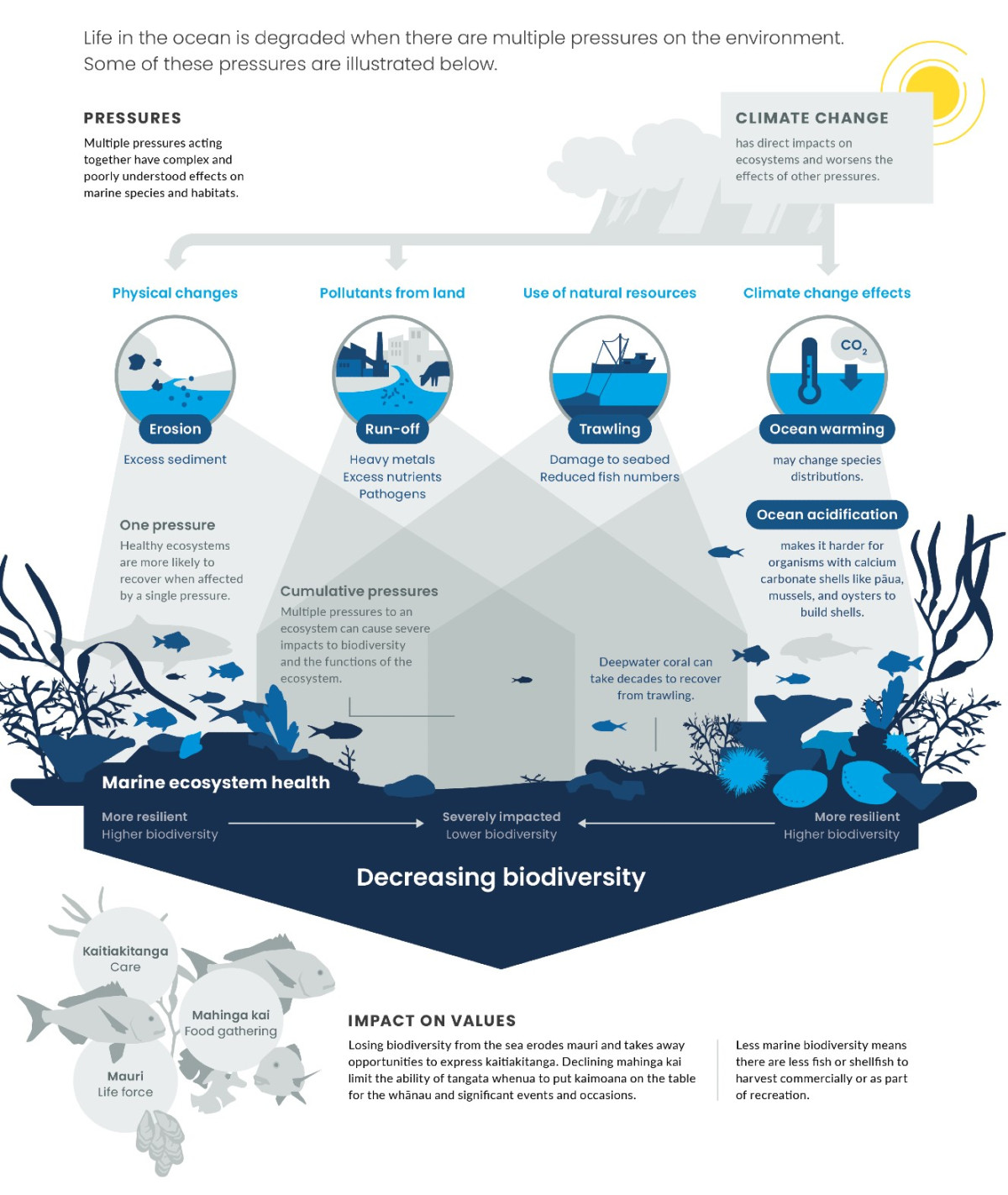

Other environmental pressures interact with fishing to increase our impact on the marine environment. Excess sediment and nutrients from rivers, urban pollution including heavy metals, plastic pollution, introduced predators, loss of habitats, and a warming and acidifying ocean all combine to put pressure on the marine environment. When combined and acting simultaneously, these pressures may have more serious impacts that are complex and hard to predict.

Fishing affects the whole marine ecosystem. Fish stocks are managed individually and do not account for interactions between different stocks or the broader marine environment. Because we don't know the cumulative effects of fishing on the marine environment, it is unclear if the current levels of fishing are sustainable or where the tipping points are.

Removing fish also changes food chains, affecting species that depend on fish for food (like seabirds and marine mammals), or that are eaten by them.

Seabed trawling changes the physical structure of the seabed and we don't know how long it takes to fully recover.

Any accidental capture of a protected species is an issue. For example, the number of Māui dolphins caught has declined in recent years, but this is a critically endangered animal and in 2015/16 there are only an estimated 63 animals left.

Overfishing can lead to loss of livelihoods. For commercial fishers, depleted fish stocks could mean catching less or having to go out further to catch fish.

Overfishing removes opportunities to harvest kaimoana. The loss of biodiversity erodes the mauri of the marine environment and impacts key values such as ahikāroa, mana, manaakitanga (acts of giving and caring for), and whanaungatanga (community relationships and networks).

New Zealand’s marine environment faces increasing pressures from activities besides fishing. This includes the effects of excess sediment and nutrients from rivers, plastic pollution, loss of habitats, and climate change. These multiple and simultaneous pressures may have far-reaching and hard-to-predict effects on marine species and habitats.

Read the long description for Cumulative pressures on the marine environment

Life in the ocean is degraded when there are multiple pressures on the environment. Some of these pressures are illustrated below.

Pressures

Climate change

Physical changes

Pollutants from land

Use of natural resources

Climate change effects

One pressure

Cumulative pressures

Marine ecosystem health

Impact on values

Theme 4: How we use our freshwater and marine resources

April 2019

© Ministry for the Environment