Theme 2: How we use our land

The changes we have made to our land have significantly altered the wider environment.

Image: Photonewzeland

This theme highlights two specific types of physical changes we humans have made to the world around us:

Logging native forests, draining wetlands, and clearing land have degraded a range of benefits provided by native vegetation, accelerated our naturally high rates of soil loss, and affected our waterways.

Since human arrival in New Zealand we’ve shaped our physical surroundings. Native vegetation has been extensively cleared so that the native forests that once covered about 80 percent of the country, now only cover a little over one quarter of New Zealand. Ten percent of New Zealand was once covered by wetlands – 90 percent of these original wetlands have now been drained.

In 2012, just over half of our land had a modified land cover like urban areas and non-native (exotic) vegetation. Exotic grassland (pasture) is now the largest single type of land cover and accounts for about 40 percent of our total land area. Exotic (plantation) forest covers about 8 percent of the country, concentrated in the central North Island.

The loss of native vegetation has continued in recent years, with more than 70,000 hectares lost between 1996 and 2012 through conversion to pasture, plantation forestry, and urban areas. Wetland areas have also continued to shrink, with at least 1,247 hectares lost between 2001 and 2016.

The conversion of native vegetation to pasture and plantation forestry has supported the way we live and provided our livelihoods. In 2016, agriculture contributed 4.2 percent of our gross domestic product (GDP) and employed more than 122,000 people, while forestry contributed over $1.7 billion to our economy and employed over 6,000 people. Our growing population also drives urban expansion.

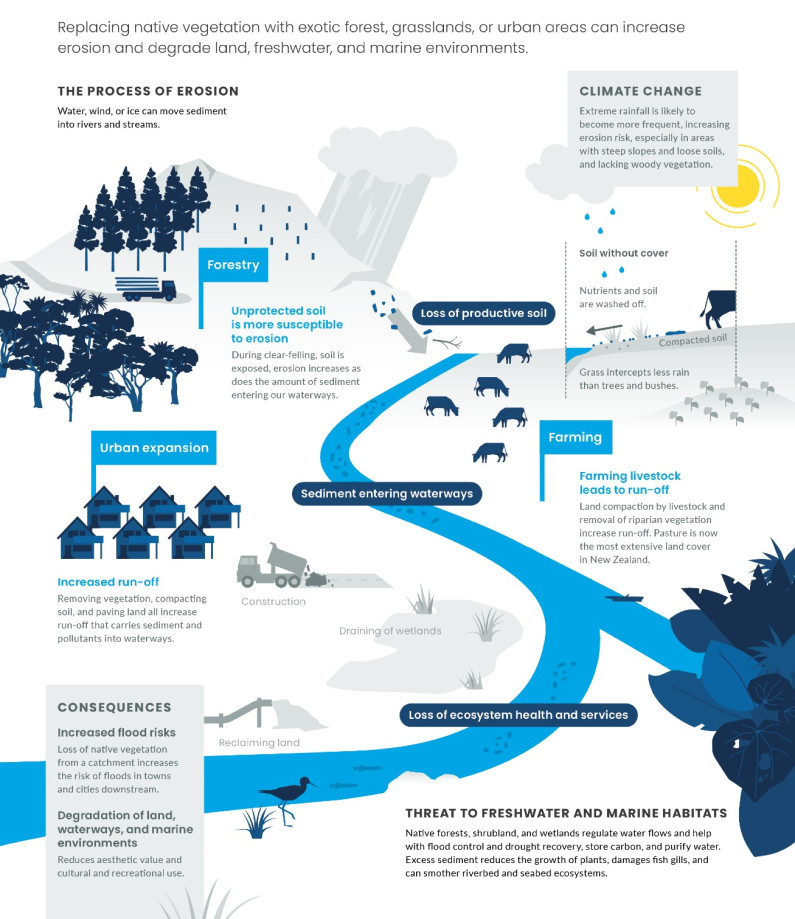

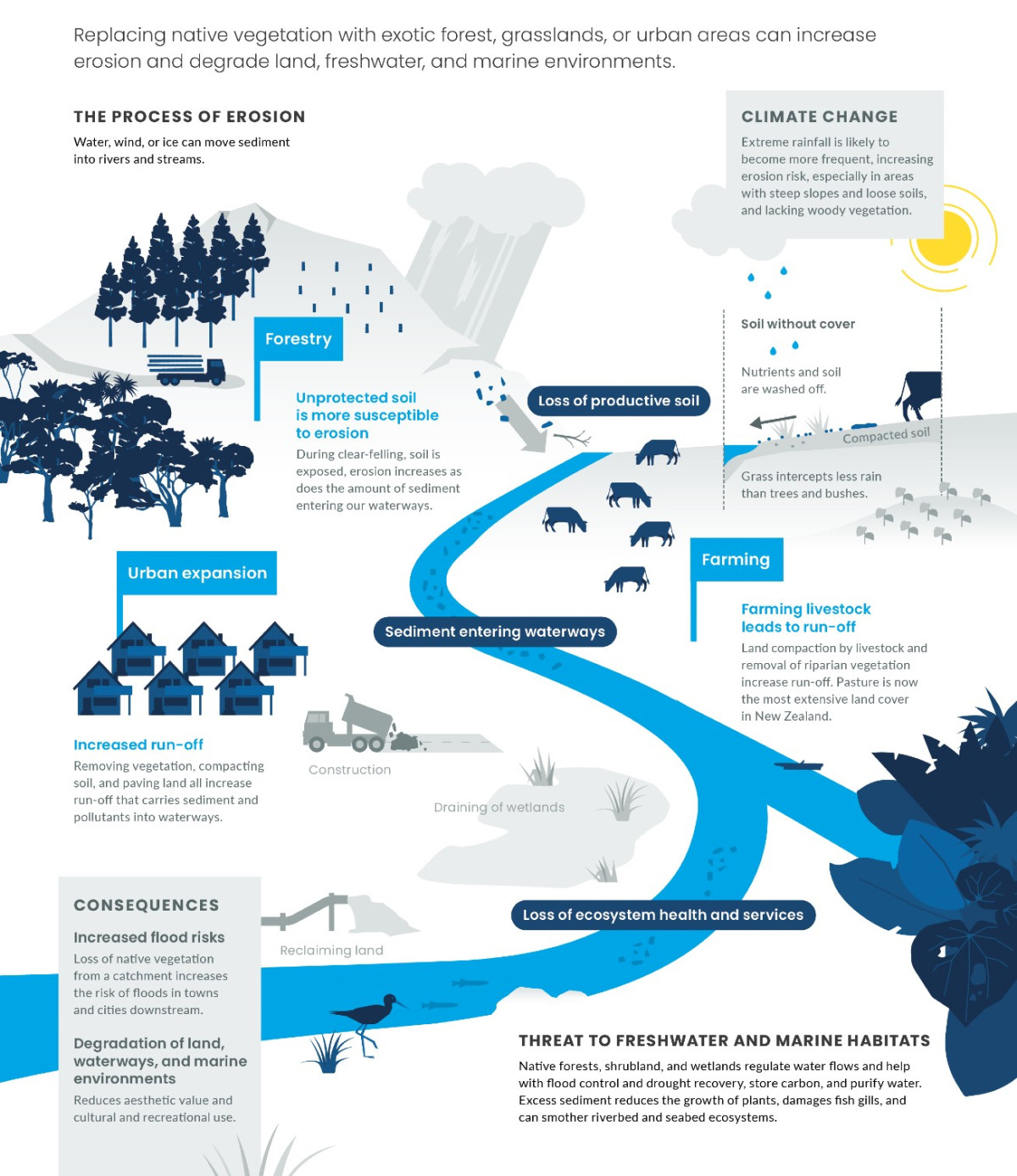

When native forests, shrublands, and wetlands are lost, we lose the wide range of benefits (ecosystem services) they provide. These benefits include regulating the flow of water in rivers and streams, recreation, storing carbon, purifying water, and providing habitats for native species. The benefits we get from simply being in nature, though not measured or quantified, could also be lost.

Loss of native vegetation has accelerated New Zealand’s naturally high rates of erosion and soil loss. A model of soil erosion shows that 44 percent of the soil that enters our rivers each year is likely to come from land covered in pasture. Once they are established, plantation forests retain soil in the same way as native forests, but harvesting by clear-felling exposes and disturbs the soil, which can then be vulnerable to erosion for up to six years after harvest.

The economic losses associated with soil erosion and landslides are estimated to be at least $250–300 million a year. Increased erosion and soil loss can also increase sediment in our rivers, lakes, and coastal environments. Too much sediment can smother freshwater and marine habitats, inhibit the growth of aquatic plants and animals, and increase the risk of flooding in towns and cities.

When ecosystems and biodiversity have been degraded, there is a corresponding effect on the extent, quality, and access to customary resources, like kaimoana.

Read the long description for The changing way we use our land

Replacing native vegetation with exotic forest, grasslands, or urban areas can increase erosion and degrade land, freshwater, and marine environments.

The process of erosion

Climate change

Forestry

Farming

Urban expansion

Consequences

Threat to freshwater and marine habitats

Growth of urban centres has led to land fragmentation and threatens the limited supply of versatile land near Auckland and other regional centres.

Most New Zealanders live in cities. According to 2018 population estimates, 86 percent of us live in urban areas. Urban areas make up a small proportion of our total land area, only about 0.85 percent (approximately 228,000 hectares) in 2012. Most urban centres have developed on our best land – often fertile floodplains near the coast – with native forests being cut down and wetlands drained (see Issue 2).

Our urban areas are spreading – the area of urban land increased by 10 percent between 1996 and 2012, especially around Auckland, Waikato, and Canterbury. Between 1990 and 2008, 29 percent of new urban areas were on ‘versatile’ land. This type of land often has the best, or ‘high-class’, soils and has many agricultural uses (like growing food), but represents just over 5 percent of New Zealand’s land.

The fringes of our urban areas are increasingly being fragmented – broken into smaller land parcels – and sold as lifestyle blocks. The number of lifestyle blocks has increased sharply in recent decades, with an average of 5,800 new blocks a year since 1998. A 2013 study found that 35 percent of Auckland’s versatile land was used as lifestyle blocks.

Urban expansion is mostly driven by population growth. Between 2008 and 2018 our population increased by 14.7 percent. Growth is expected to continue, with the highest rates in Tauranga, Auckland, and Hamilton, and lower rates in Wellington and Dunedin.

Our versatile land and high-class soils are gradually being lost to urban growth, making them unavailable for growing food.

The loss of versatile land is happening at the same time as our food production system is under pressure to increase production without increasing its effect on the environment. This loss can force growers onto more marginal land that is naturally less productive and requires more inputs, like fertiliser.

Urban growth changes the land cover dramatically – and often reduces native habitats and biodiversity. In New Zealand, native land cover accounts for less than 2 percent of land in urban centres and only 10 percent on the urban-rural boundary.

Also, many of the plants and animals people bring with them to cities can be harmful to native biodiversity. For example, cats can hunt native animals, and non-native plants in gardens and urban plantings can become problematic weeds if they spread to native areas.

Theme 2: How we use our land

April 2019

© Ministry for the Environment