By national and international standards, the West Coast region receives a generous and reliable rainfall. Near the Main Divide this exceeds 8,000 mm annually and declines to 2,000 mm at the coast. The mid- to upper Grey Valley possesses the lowest rainfall in the region (West Coast Regional Council, 2005). The West Coast Regional Council (WCRC) reports that issues associated with highly allocated catchments and aquifers are not yet experienced on the West Coast due to the quantity of the region’s resource and low demand pressures. The council maintains that as a water-rich region with low demand, the proposed NES “has little relevance for the West Coast in terms of any need to improve water management”43. A limited number of takes are currently measured.44

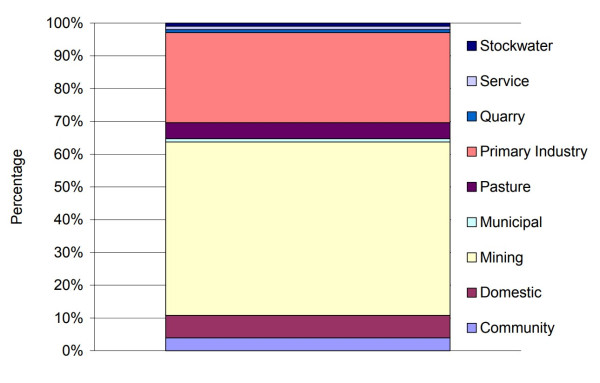

The Ministry for the Environment’s consent database suggests that the total annual allocation of consented water takes on the West Coast is 271 million m3/annum, 90 per cent of which is sourced from surface water. Fifty-four per cent of consented water take is associated with the mining industry (Figure A1). The WCRC reports that although water take by the mining industry is consented, it is not consumptive because it is primarily related to “dredge ponds” and is returned to the environment following settling.44 If mining is ignored, consumptive take on the West Coast is 127 million m3/annum, just 1.3 percent of the national consented annual allocation (≈ 9,908 million m3/annum) of water take.

Figure A1: Consented abstraction, by use type

- There is almost universal agreement among stakeholders that the measurement of consented water take will help improve the management of New Zealand’s freshwater resource. The potential for this kind of improved management is delayed under the status quo. Existing studies indicate that New Zealand residents place high value on the protection of the natural environment, and on this basis it is reasonable to assume that improvements in the management of freshwater resources and environmental flows will be accorded a high value by New Zealand residents.

- Compliance monitoring and enforcement will be improved. In the absence of water-measuring devices this is so imprecise and inaccurate as to only be useful for blatant non-compliance, such as that occurring during times of restriction.

- Confidence in water resource management will be improved by the measurement of consented water take, and improved public confidence may result in reduced transaction costs in resource consent decision-making.

- The proposed NES will improve the ease and effectiveness with which actual water take can be reported. Measuring actual water take is important for achieving and demonstrating improved efficiency at all levels (individual, industry, regional and national). At the national level the proposed NES will allow complete physical water accounts to be compiled within five years of the regulation being gazetted. This will assist the understanding of the effects of environmental policy on the economy, and of economic policy on the environment. It will also help New Zealand to meet its international obligations to report the status of and changes to its natural environment.

- Technical efficiency gains for existing consent holders from the enhanced monitoring and management of systems performance have not been quantified. However, stakeholder interviews and the literature suggest that there can be benefits from consented water users monitoring the actual water taken, which in some situations may offset the cost of installing and maintaining a water-measuring device.

- There is the potential for water allocation to be made more efficient from knowing just how much water has been taken − although this benefit only occurs where water is scarce. In the absence of data on the actual take, determining the reasonable needs of consented water users is based on relatively simple models, and allocation is often based on these same models. Hence, the availability of data describing actual take will allow for fairer and more efficient allocation through:

- identification of un-utilised allocation

- refinement of estimates of the degree of effective catchment allocation

- improved resource understanding, allowing for less conservatism in

the setting of allocated volumes at the catchment level.

- Aqualinc estimate that knowledge of actual water take has the potential to free up to 5 to 10 percent of the allocated volume in what are considered to be highly allocated regions.2

43 West Coast Regional Council, submission on proposed NES.

44 Simon Moran, West Coast Regional Council, July 2007.

2 John Bright, Aqualinc Research Limited, personal communication, July 2007.

See more on...

Annex III: West Coast Regional Council

May 2008

© Ministry for the Environment