Better planning for a better New Zealand

We are building a modern planning and environmental management system that meets New Zealand’s needs today and our aspirations for tomorrow. The new system is designed to unlock growth, reduce the costs of much-needed infrastructure, protect the environment and improve resilience – all while freeing up property rights so landowners have certainty and control over their land. The new system will make it easier for New Zealanders to get things done by focusing on what is important, making national rules simpler, increasing standardisation, creating one plan per region, setting binding environmental limits, and making better use of data and technology.

The Government is fundamentally transforming the way New Zealanders plan, develop and can enjoy our land, manage resources and care for the natural environment. We’re building a new planning system that delivers on our commitment to unlock infrastructure and housing development, support New Zealand’s primary industries, and drive significant economic growth all while protecting what is important.

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is broken and no longer fit-for-purpose. It has become a major barrier to progress. It’s made it too hard to build what we need, holding back growth while failing to protect the natural environment.

The new system will be a game changer. It is a once-in-a-generation shift towards growth, choice and possibility.

At its core, it’s about making it easier to get things done while protecting what really matters. It will make it easier to build what we need, deliver the energy that powers our lives, and grow the exports that underpin our economy. Expected outcomes include:

This is an opportunity to unlock growth and improve environmental outcomes by replacing unnecessary red tape with reasonable rules. But it’s about far more than replacing the RMA. We’re building an entirely new system that works for all New Zealanders – one that makes it easier to get things done.

| Hon Chris Bishop Minister Responsible for RMA Reform |

Simon Court Under-Secretary to the Minister Responsible for RMA Reform |

We are building a modern planning system that meets New Zealand’s needs today and our aspirations for tomorrow.

New Zealand’s current resource management system is not delivering for people, the economy or the environment.

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is confusing, costly and inconsistent, making it hard to build homes and infrastructure, while environmental outcomes continue to decline.

National direction and plans are complex, with many different rules across the country. This forces councils to spend time interpreting and processing even minor applications, leaving less time for big-picture planning.

There are more than 1,100 different planning zones, each with its own rules. Because rules vary so much across New Zealand, people don’t know what to expect. This lack of consistency makes it harder to build and harder to invest in a coordinated way.

Decisions are slow because decision-makers lack access to high-quality data. The digital systems people rely on can be disconnected, making it hard to navigate information to make decisions on their property, or track consents as they are being processed. Without reliable information, councils are often forced to make decisions one at a time instead of planning ahead with confidence.

The current resource management system focuses on short-term fixes, not long-term goals. It’s time for change.

The proposed new system will make the enjoyment of property rights a guiding principle of reform – so people can do more with their property. By clearly defining what can be regulated, it will be more efficient and fairer, while still protecting the environment and public interests.

The system is designed to unlock growth and reduce the costs of much-needed infrastructure. It will make it easier for New Zealanders to get things done by:

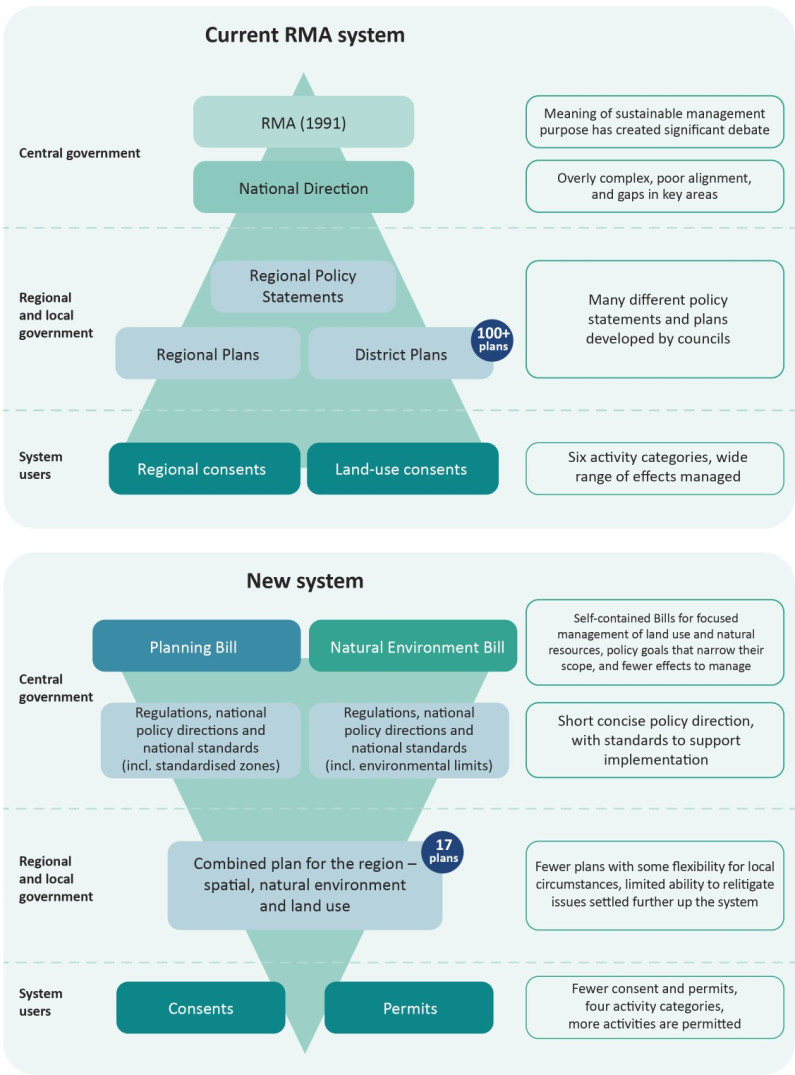

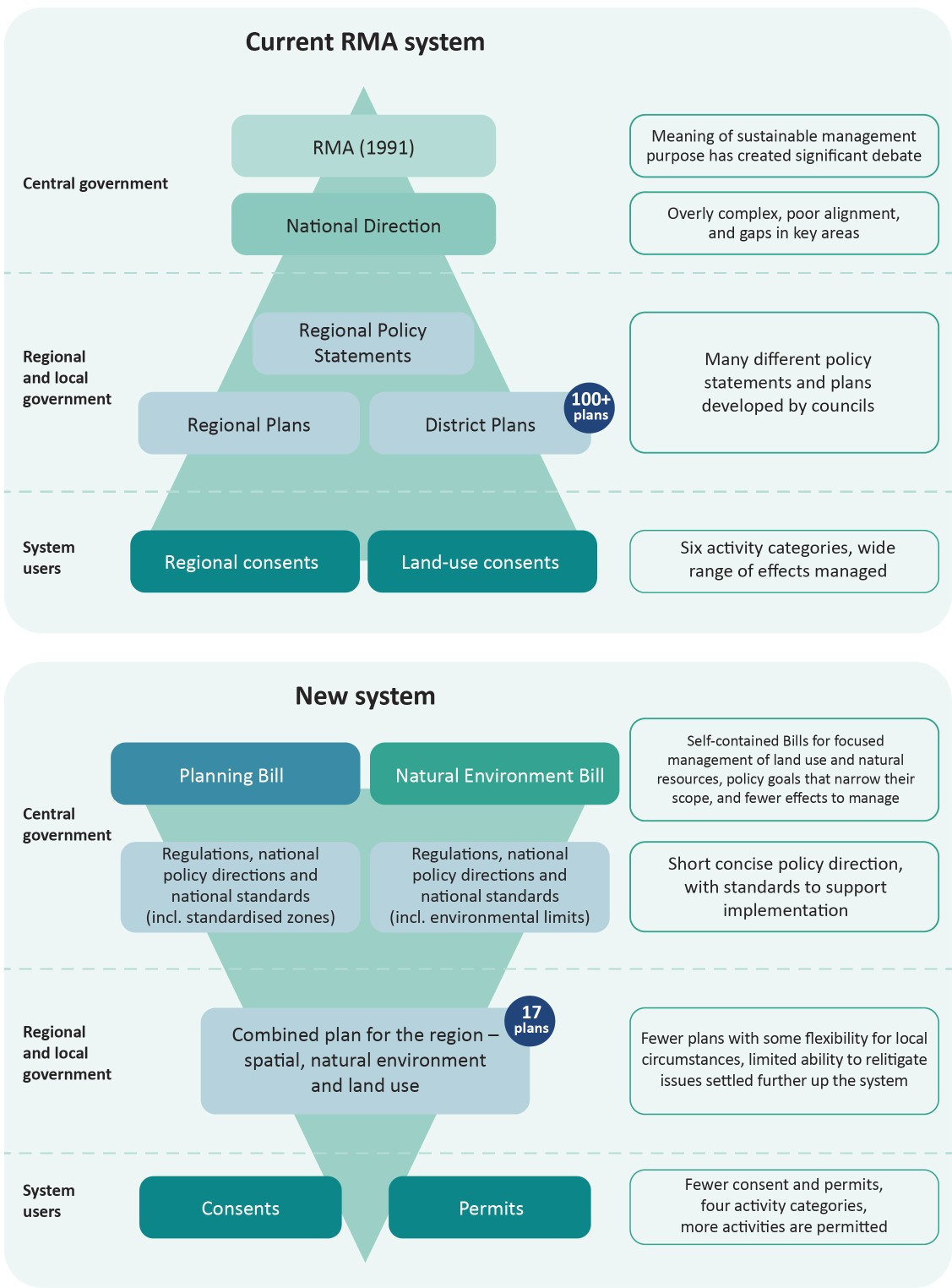

We will replace the RMA with two Bills that separate land-use planning and natural resource management.

The RMA regulates town planning, resource management and environmental protection under one Act. The system is complicated and expensive, making it hard for the RMA to support development or protect the environment effectively.

A major change in the new system is the shift to two separate Bills:

The new planning system is based on a blueprint1 developed by the Expert Advisory Group on Resource Management Reform. The blueprint was developed to align with the principles decided by Cabinet in 2024.

1 Blueprint for Resource Management Reform: A Better Planning and Environmental Management System 2025.

The new Bills give clearer direction to decision-makers and make the system more consistent and predictable for users.

The RMA’s broad and open purpose clause2 and lack of clear goals have led to confusion, legal disputes and poor outcomes, as people interpret and apply it differently.

The Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill will each have:

The goals in each Bill drive the outcomes of the system. They set out what the system must achieve and what can be regulated. The goals help to:

If something is not covered by the goals, the system won’t be allowed to manage it. It’s that simple.

2 To ‘promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources’.

We need a disciplined focus on a system design that achieves simplification rather than further complexity. We need to ensure the solutions we develop are within our collective capacity to implement well.

And we need to build a system that can achieve broad and enduring consensus across society, so as to put an end to the ‘flip-flopping’ of RMA reform that has meant long-identified solutions to issues that have not been implemented.

| The Natural Environment Bill will: | The Planning Bill will: |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

To establish a framework for planning and regulating the use, development and enjoyment of land.

To establish a framework for the use, protection and enhancement of the natural environment.

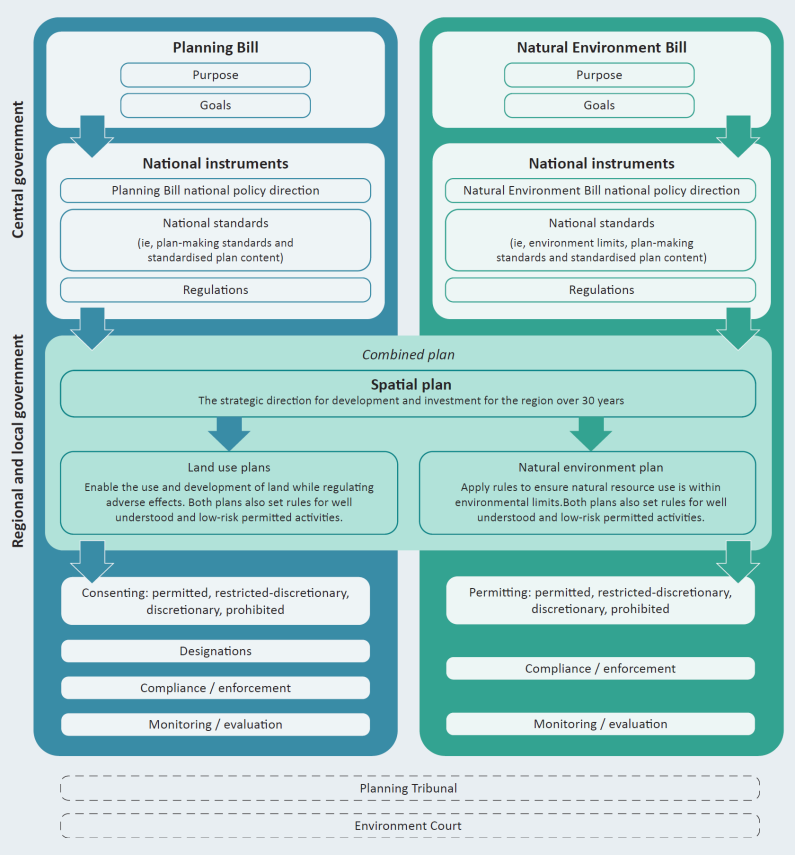

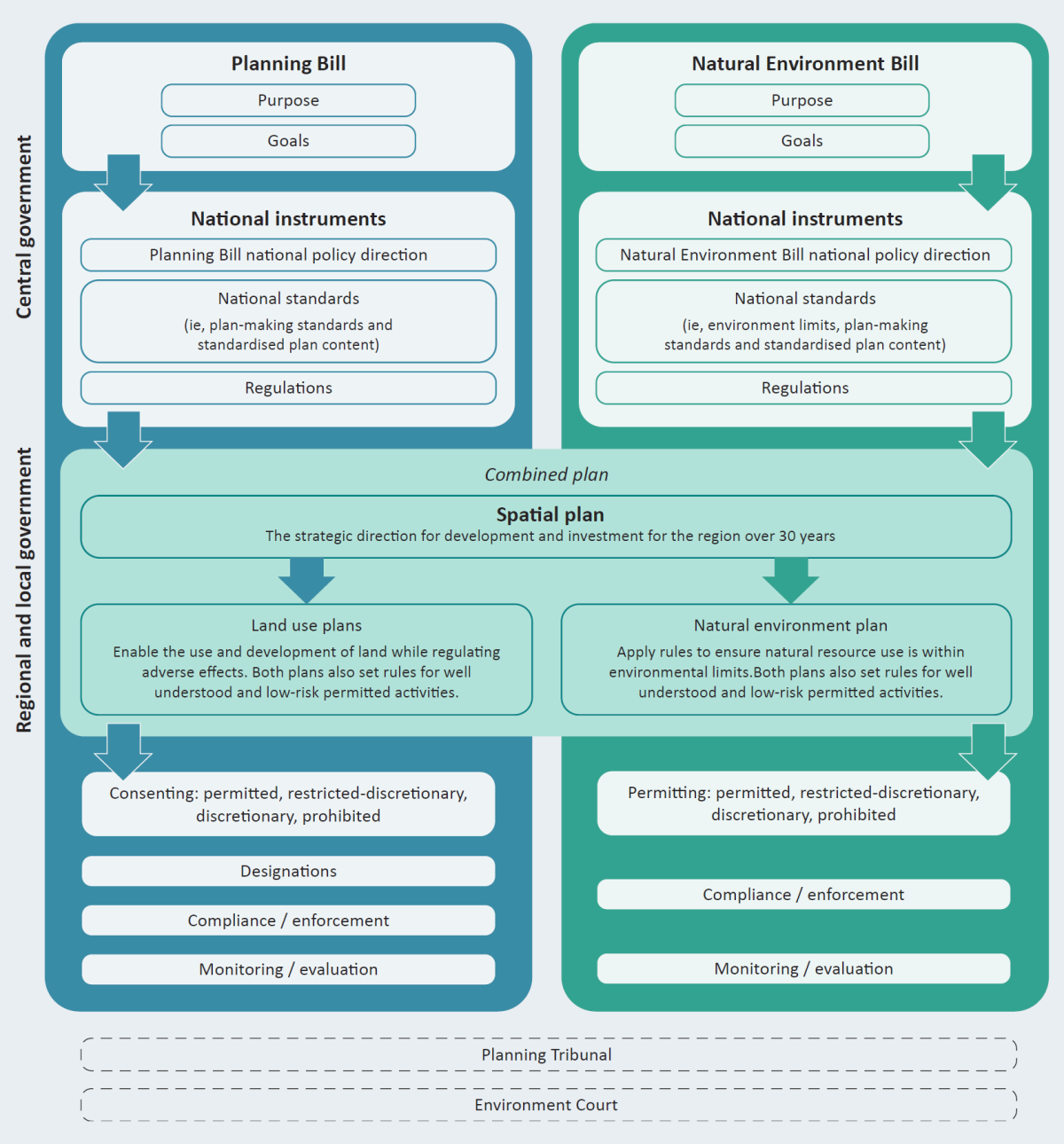

Decisions in the new system will work like a funnel. Clear goals are set at the top, then national policy direction and standards narrow what’s up for debate from there. This means decisions will stick, and investors, communities and developers have certainty.

The new planning system is all about certainty. Decision-making will work like a funnel (see figure 1), with each Bill starting with clear goals (for example, to plan and provide for infrastructure to meet current and expected demand) that narrow what can be considered at each level of the system. This will make it clearer from the start what is allowed.

At each level of decision-making, fewer things will be up for debate, and earlier decisions can’t be relitigated. This will make the system simpler and more efficient, with more activities allowed by default and fewer consents and permits needed.

National policy direction (NPD) for each Bill will provide policies, objectives and directives on the goals, including outcomes and actions that need to be included in plans.

National standards will put the NPD into action, making sure policies are applied consistently across the country for things like land-use and environmental protection. This will simplify the planning system. National standards can apply nationwide and will also give direction on environmental limits. Other kinds of national standards will have direct effect on activities ‘on the ground’, without having to be first incorporated into planning documents.

Regional combined plans will be the combined plan for the region. They will include:

Consent and permit decisions will sit at the bottom layer of the funnel. The system will be more standardised and permissive, regulating a narrower range of effects. This reduces the number of consents (for land use) and permits (for natural resources), and leads to more efficient consent processes.

The funnel approach makes the system more directive from the top, ensuring consistency across the country, and allowing local communities to focus on applying that approach in their area. It would make decision-making more focused at each stage of the planning system. As the process narrows, fewer things would be up for debate, saving time and money. It would also give people greater certainty about what they can and can’t do, helping them understand likely outcomes before they begin.

Landowners will be able to do more with their property and councils will be freed up to focus on managing what matters most.

Under the RMA, even the most minor effects from an activity have to be considered across a broad range of matters. This means more consents are required and they’re harder to get, creating hurdles for people trying to carry out everyday projects. For example, the RMA requires houses to have a certain-sized storage area outside bedrooms and kitchens.

This has caused too much regulation, made it expensive to follow the rules, and slowed down important development.

The new planning system has fewer effects that are able to be considered. That means less-than-minor effects and those that are barely noticeable3 will generally not be controlled.

The new system will take a much more proportionate approach to regulation, narrowing the types of effects councils can regulate. More activities won’t need a consent, making it easier to build.

Effects that will be in scope of the Planning Bill include risks related to natural hazards, neighbour-to-neighbour impacts like noise, vibration and shading, and the benefits of increased housing supply and infrastructure capacity (including roads).

Effects that will be out of scope of the Planning Bill include matters internal to a site (like building layout or balconies), visual amenity, private views, and negative impacts on competing businesses. Subjective landscape and amenity effects that preserve character will also be excluded, except to protect outstanding natural landscapes and features, areas of high natural character in the coastal environment, wetlands, land and rivers and their margins, and significant historic heritage.

The new system will also:

3 Bearing in mind that cumulative effects may add up to more-than-minor effects.

The national framework for decision-making will be clearer about what is most important and how to manage conflicts.

One of the critical failures of the RMA was a lack of early national direction to guide planning and decisions. Decision-making is complex and confusing because there are too many conflicting rules, which often overlap with other laws, local plans and each other. This makes it hard for people to know what they’re supposed to do.

National instruments in the new system will take a different approach. They will provide simpler, clearer and more standardised direction for decision-making and plans. ‘National instruments’ is the collective term for the suite of secondary legislation comprising:

These instruments tell decision-makers what needs to be achieved, and how to apply that direction through plans and other decisions. This will help create consistent processes, ensure nationally consistent approaches to managing activities and effects, and set standard content for plans.

The NPD under each Bill will be a short, targeted document that sets the direction, with objectives and policies that everyone must follow. Having one NPD under each Bill will:

National standards will sit below NPDs, implementing the NPD policies and objectives. They will provide the more detailed and technical direction needed for implementation.

They will also establish standardised and nationally consistent approaches to planning for and regulating land use and natural resource management, including standardised zones and environmental limits.

In addition to the national instruments, both Bills will contain regulation-making powers that will enable consistent processes and methodology to be prescribed. Regulations will be focused on administrative and other matters that require urgent or frequent updates, such as emergency responses.

We propose to deliver national instruments for the new system in two main stages. This will ensure councils receive timely and targeted direction for spatial planning, while allowing more technical and regulatory plan standards to be developed and introduced at a later stage. The new process will be shorter and less cumbersome than at present, while providing for public input.

We are aiming to have the first core suite of national instruments to inform spatial plans by the end of 2026, which will include:

The second core suite of national instruments is to be delivered in mid-2027 and will include:

Some components of the new national instruments will build on existing (or soon-to-be-finalised) RMA national direction. But to truly deliver on the ambition of the new Bills, all current instruments must be assessed and restructured to align with the new system.

This is necessary because many current instruments are organised by topic or sector, which may not correspond with the new system’s goal-based approach. Additionally, there are system goals (such as the protection of significant historic heritage and the identification of sites of significance to Māori) that are not addressed by existing national direction.

National direction recently developed or amended under the RMA is already more closely aligned with the new Bills. These updates will be readily integrated into the new system, helping us hit the ground running.

There are two processes to develop and amend national policy direction and national standards under the Bills:

We are introducing a more standardised and streamlined approach to planning how we use land and manage natural resources.

Under the RMA, most councils have developed customised district and regional plans. These plans have been criticised for failing to deliver the desired outcomes, while being costly, complex, inconsistent and difficult to use.

The designation process for setting aside land for public projects like roads, schools and utilities is also slow, complex and costly, with duplication and relitigation at different stages.

Spatial planning in New Zealand is mostly optional4 and varies in quality and content.5 Spatial plans also lack legal power to direct land, transport and funding plans, which can slow down how quickly they are put into action.

A key feature of the new system will be a more standardised approach to council plans with a regional combined plan that brings together:

All councils in the region will jointly prepare regional spatial plans. The plans will:

Each district or city council will prepare land-use plans, and each regional council will prepare a natural environment plan. A unitary council would prepare both. A land-use plan will enable the use and development of land, while regulating adverse effects. A natural environment plan will set out how the effects of the use of natural resources in that region are managed, including managing within environmental limits.

Land-use and natural environment plans must follow national instruments and regional spatial plans. Most of the plan content will be standardised, with flexibility to include customised rules for local needs.

When plans use standard rules that have already been decided nationally, the public can give feedback on where those rules apply but not on what the rules say. When plans include customised local rules, people can give feedback on both the content of those rules and where they apply.

Plans will include objectives (the outcomes to be achieved), policies (the actions to deliver those objectives), and rules (which will have legal effect) and methods to support the implementation of both.

A reduction in the number of plans, from more than 100 plans to 17 regional combined plans, along with greater standardisation and a more streamlined process, will mean plans are quicker to prepare and easier to use.

4 The Local Government (Auckland Council) Act 2009 requires Auckland Council to prepare and adopt a spatial plan for Auckland.

5 The National Policy Statement for Urban Development requires future development strategies for 13 urban environments, but these are mainly focused on long-term housing and development capacity.

Table 1: Regional combined plans

| Plan | Bill | Council responsible | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional spatial plan | Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill | All regional, district and unitary councils in a region | To provide strategic direction for growth and infrastructure and enable strategic integration of decision-making between the Planning and Natural Environment Acts |

| Natural environment plan | Natural Environment Bill | Regional councils and unitary councils | To regulate use and protection of natural resources |

| Land-use plans | Planning Bill | District councils and unitary councils | To regulate use and development of land |

The new system would improve the designation process by allowing infrastructure needs to be identified and protected earlier, especially through spatial planning. There would be two main pathways available for designating land: a spatial planning process and an improved, less onerous version of the current process. Once a proposed designation is in place, a construction project plan could be submitted to manage how the work is done (and not whether the work can be done).

We are standardising rules across the country to make the system more consistent and user-friendly, saving people time and money.

Under the RMA, councils can create their own rules and approaches for land use and natural resource management. One of the key areas of variation and complexity across the country is the use of zones and overlays. These are mapped areas within a district or region where specific rules and standards apply, providing certainty about what activities are allowed where.

Zones separate land uses that don’t work well together. City and district councils prepare district plans that set out zones for land use and subdivision.

This has resulted in more than 1,100 different zones across the country, with wide-ranging differences in rules and definitions for similar types of land or activities. This increases cost and uncertainty for everyone involved.

Overlays can set stricter rules than zones, sometimes requiring a resource consent for activities that would otherwise be permitted under the underlying zone rules.

National standards will include standard rules for things like zones and overlays, how to manage certain activities and consent conditions, and how plans and maps should be structured. Consistent rules across the country will:

In addition to the national instruments, both Bills contain regulation-making powers that enable central government to establish nationally consistent rules, set procedures, and provide technical detail to support their implementation.

The Planning Bill and the Natural Environment Bill empower the Governor-General to make regulations by Order in Council. Regulations may address administrative, procedural, financial, compliance, enforcement and emergency matters. This flexibility allows the government to respond to emerging issues, ensure regional consistency, and clarify technical aspects of the resource management system.

We are reducing the need for consents and permits, and making it faster, cheaper and easier to get consents when they are needed.

Under the RMA, resource consents are required for most activities that are not expressly permitted by a plan, rule or regulation. There are six activity categories, and the consenting process is often slow and costly, relying heavily on case-by-case decision-making.

Many types of effect are regulated, and there is significant variation in how councils interpret and apply rules. There is also a low threshold for limited notification and participation.

The new system simplifies activities into four categories:

The new system will no longer include the RMA categories of non-complying and controlled activities. The non-complying activity category has a high threshold, making it very difficult to obtain consent.

Under the Planning Bill and the Natural Environment Bill, more activities will be permitted without the need for a consent or permit, particularly those with less-than-minor adverse effects. Where consents or permits are required, most will be restricted discretionary activities, meaning assessments will be limited to the criteria set out in the relevant plan.

This is an effective way of focusing assessment on the effects that matter, and because assessment is restricted to listed matters the applicants will know in advance what will be considered.

The new system will:

This streamlined consenting process will be faster and cheaper, increase certainty and reduce the number of consents required.

Limits will be set to protect the natural environment and human health, and new approaches will be rolled out over time to allow fairer allocation of scarce resources.

Environmental protection under the RMA mainly involves managing the negative impacts of individual developments. However, the absence of strong, stable and clear environmental limits across all domains has resulted in unintended outcomes – some of which are difficult to reverse.

Under the new system, central and local government decision-makers will be required to set binding environmental limits informed by environmental data and communities’ aspirations. Central government will set national limits to protect human health, informed by Ministry of Health guidelines. Regional councils will set limits for the natural environment in their respective areas following nationally directed methods. These limits will both apply to air, freshwater, coastal water, land and soils.

The Government will retain flexibility to be able to set minimum levels for ecosystem health. There may be circumstances where a council and community consider it appropriate to set less stringent limits to those set by the Government, which is possible provided a justification report is prepared.

Setting limits will require a decision-maker to balance the protection of human health and the life-supporting capacity of the natural environment with social and economic aspirations of the country and the region.

Limits will be linked to specific geographic areas (management units), and resource use must be capped or managed through action plans. Exceptions will be available for critical infrastructure – but the limit will still apply, and the action plan will need to set out how the limit will be managed back to, over time.

Setting clear and transparent environmental limits will:

Under the RMA, the taking or use of natural resources such as water, coastal space and discharge capacity is allocated through a combination of permitted activities and consents. Consents are generally granted to applicants in the order they are received, and existing consent holders seeking replacement consents have priority over new applicants.

This approach is inefficient and inequitable when resources are scarce. It does not incentivise the most efficient or highest-value use of resources, and it has disadvantaged Māori and new entrants. It means those who apply first can secure long-term rights, potentially locking out others who might deliver more benefit to the public.

The Natural Environment Bill initially retains the RMA’s allocation approach, including ‘first-in, first-served’. Over time, national instruments will enable new ways to allocate resources by type or by region. These may include market-based approaches and comparative consenting. Where this is possible, it will make resource use more efficient, especially when in short supply, helping New Zealand’s economy.

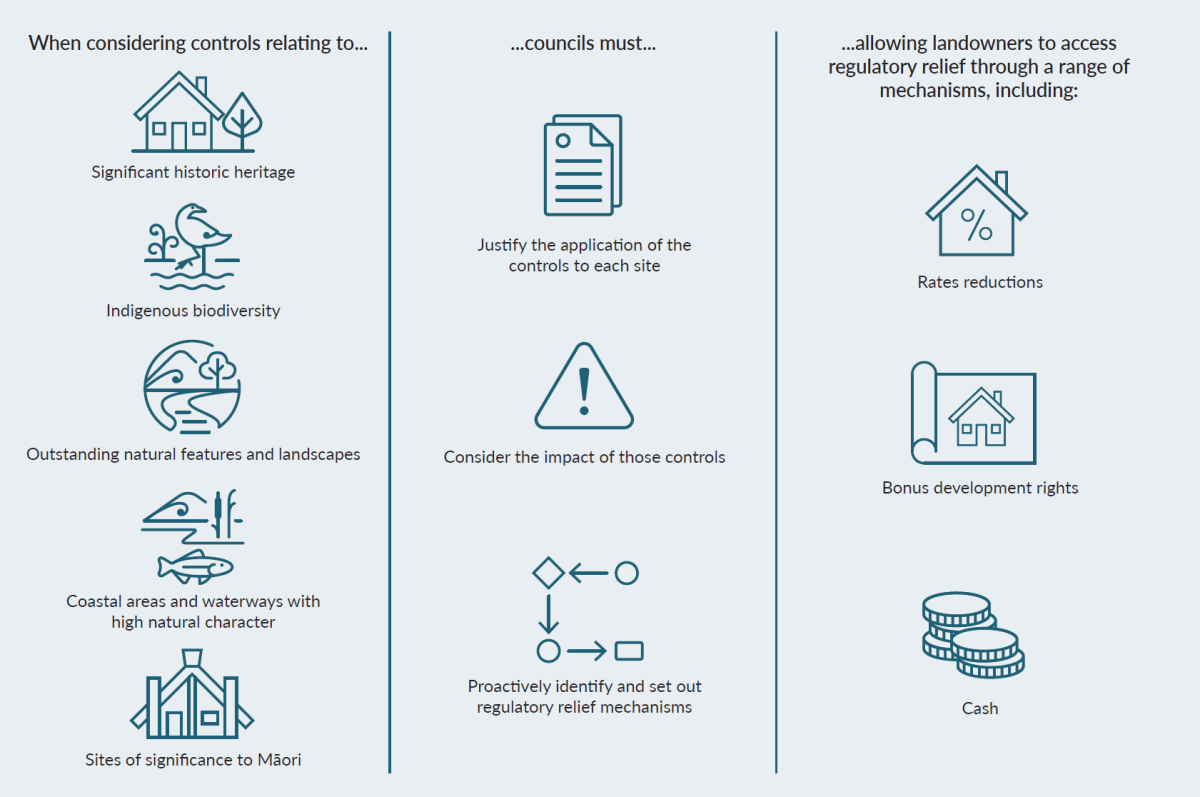

We are introducing better recognition of the impacts on landowners when some planning controls limit the use of their land.

Under the RMA, planning controls imposed by councils can impact how landowners are able to use their land. Access to relief for such regulation is limited to only extreme scenarios where the land is considered incapable of reasonable use.

The new system will introduce a new regulatory relief framework that requires councils to consider the impact of some planning controls on landowners when they are developing plans. Councils will have to provide relief where this impact is significant, and the threshold for relief will be lower than under the RMA.

These planning controls are:

The framework will apply to all privately held land, including private property in the coastal and marine area.

Councils will be able to use a range of tools when providing relief, including cash payments, rates relief, bonus development rights, no-fees consents, land swaps, and access to grants or expert advice. The Planning Tribunal will have a role in resolving disputes about how councils have provided relief.

The new system will also provide a pathway for landowners who face severe or unforeseen impacts from planning controls, regardless of whether those controls are covered by the regulatory relief framework.

Compliance and enforcement will be stronger in the new system.

Weaknesses in the current system have led to inconsistent and often poor enforcement of the RMA. Responsibility for compliance and enforcement is spread across many councils, each with different approaches and levels of resourcing. Some councils do more than others, and about half report no enforcement actions in a typical year. Without central oversight or standard practices, enforcement is uneven and creates uncertainty for users of the system.

Ensuring people comply with planning and environmental management laws is essential for the system to work properly and achieve its goals. The new system shifts the regulatory focus from case-by-case consenting to ensuring compliance with nationally standardised rules. This is a significant shift, and it will require stronger compliance and enforcement.

We have strengthened the core compliance and enforcement components compared to the RMA and added new provisions. This includes measures to:

The Government is taking advice on whether to establish a national compliance and enforcement regulator with a regional presence to administer the compliance and enforcement functions under the new system. If progressed, the new regulator would be established through a separate legislative process, and is not proposed in this legislation. A national regulator’s functions could include:

We aim to provide more certainty about how Māori interests and the Treaty of Waitangi are provided for within the new system, and better enable the development and protection of Māori land.

The RMA provided for Māori interests and Treaty of Waitangi obligations through a mix of general and specific provisions, including a general requirement to take into account the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. The general provisions required interpretation and, along with other aspects of the RMA, created uncertainty and complexity.

The new system aims to provide more certainty for all users of the system about how Māori interests and the Treaty of Waitangi are provided for. Māori interests will be provided for higher up in the system through involvement in national instruments and plan-making.

The Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill will include descriptive, non-operative Treaty clauses that list specific provisions in each Bill that relate to the Crown’s obligations under the Treaty.

The goals in both Bills set out the strategic outcomes for the system and will work alongside a specific goal that will provide for Māori interests. That goal will provide for Māori interests through:

Policies and objectives for this goal will be set through national policy direction and national standards, which councils will have to give effect to when developing plans under the new legislation. Councils will work with tangata whenua to identify sites of significance and apply the prescribed rules and policies in national standards.

The legislation will include clear requirements for iwi participation in the development of national instruments as well as regional combined plans (these are set out in table 2). The intent is that providing for Māori interests through national instruments and planning will provide more certainty for consent decision-makers about how these interests should be considered.

Table 2: Provisions for Māori interests in the proposed new system

| Processes in the new system | Provisions for Māori interests |

| System goals |

|

| National instruments and standards |

|

| Planning |

|

| Consents and permits |

|

Many Treaty settlements interact with the RMA in a variety of ways. The Government has committed to upholding Treaty settlements and related arrangements that interact with the RMA in the new system. The new legislation reflects this commitment by:

Additional provisions to provide for specific arrangements under Treaty settlements and Ngā Rohe Moana o Ngā Hapū o Ngāti Porou Act 2019 may be included in the legislation during the legislative process, subject to the agreement of all relevant parties.

Table 3: Changes for different sectors

| Sectors | Key changes |

| Infrastructure providers |

|

| Property developers and homeowners |

|

| Farmers |

|

| Aquaculture |

|

| Mining operators |

|

| People who participate in the system |

|

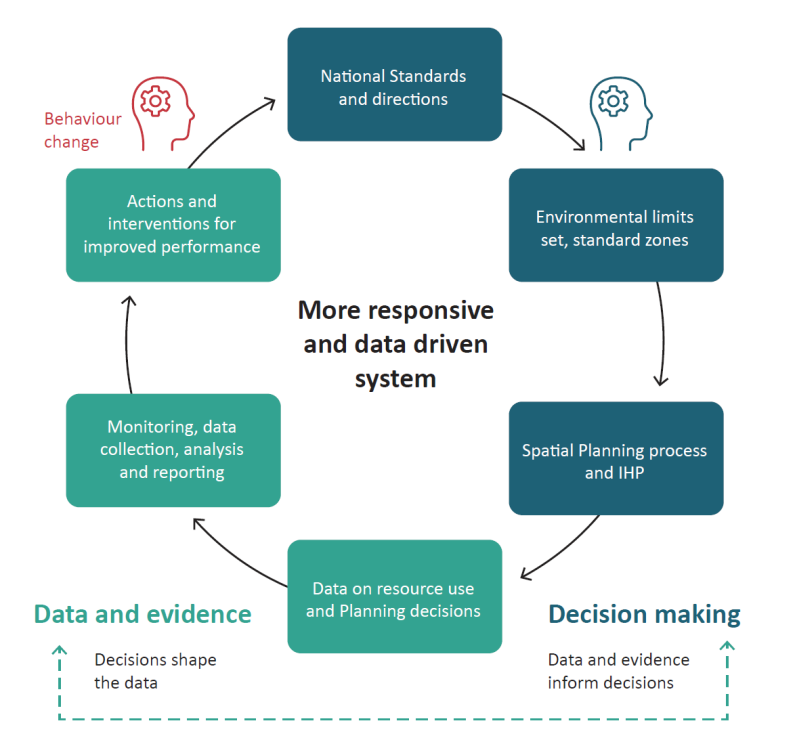

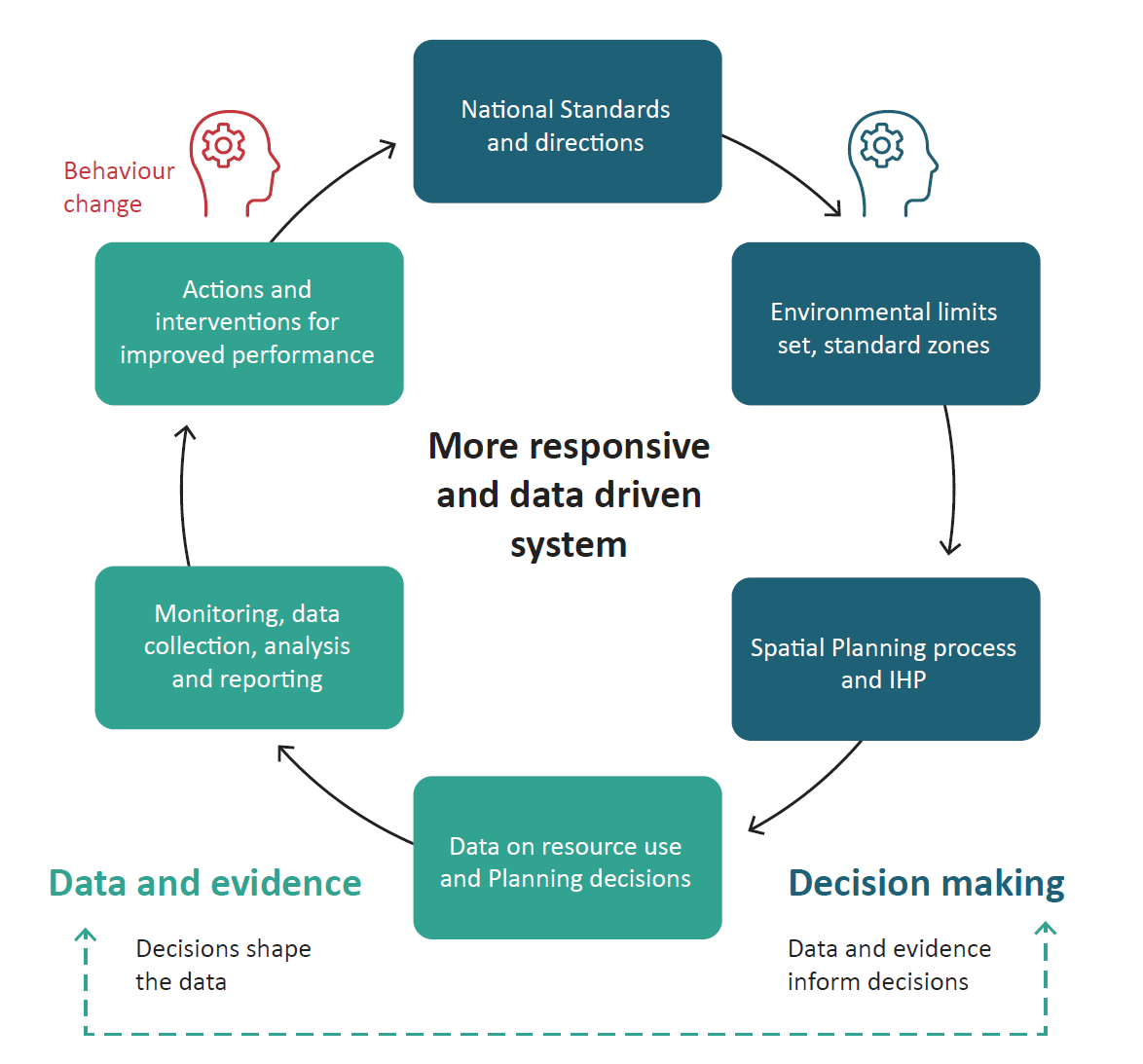

We are moving to a modern data-driven and digitally enabled system that is simpler, easier and faster.

Poor outcomes under the RMA are not just due to how the system was built – they also come from the way it has been implemented. Inconsistent rules and outcomes across the country have largely resulted from a lack of national guidance, limited investment in data and monitoring, and inconsistent enforcement practices. We want to avoid making the same mistakes. The new system will require regular reporting on how the system is working to deliver key outcomes so we can get in and fix things quickly.

We are working on ways to make the new planning and environmental system data-driven and digitally enabled for a modern New Zealand.

The system will be more efficient, better connected and easier to use. A more standardised approach will help us use new technologies like artificial intelligence. This means people can access clearer information and advice about their property, while also supporting faster and easier consent processes.

It will be easier to track whether the system is meeting its goals – allowing the use of natural resources while staying within environmental limits.

Under the RMA, each regional council produces a regional plan, and each territorial authority produces a district plan. Having so many separate paper and digital plans across the country makes it hard for people to understand the rules.

Under the new system, each region will have one combined plan that follows a standardised format and structure. The intention is to host these plans on a national e-planning portal so they are more accessible and user-friendly. The national e-plan will be updated whenever national or local planning rules change so everyone is working from the latest version.

Monitoring and evaluation of system performance has been limited under the RMA, with few feedback loops to support learning and continuous improvement. A system performance framework will be the key central government tool to track the implementation of the new system and its ongoing operation.

It will track how the system is delivering outcomes in housing, infrastructure, growth and environmental protection. It will also provide decision-makers with information and insights they can use to ensure the system is efficient, responsive and aligned with Government priorities.

The framework will consist of:

The Environment Court currently handles most appeals and disputes under the RMA, but this creates a heavy workload. It can also be costly and complex, making it hard for some people to access. The Government plans to set up a planning tribunal to deal with smaller disputes more quickly and affordably. The Environment Court will still handle more significant cases. This will also provide an accountability mechanism to ensure the new system is embedded and applied as intended by decision-makers, as there is easier access to challenge of out of scope or disproportionate decision-making.

Under the RMA, local councils cover most planning, consenting and compliance and enforcement costs, using a mix of rates, user charges and some government grants. Central government pays for national policy.

This means ratepayers and taxpayers often carry the cost, rather than those using the system. Under the new system, councils will continue to recover costs from users.

New planning processes will get underway quickly when the Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill are passed into law.

| Late 2025 | The Government introduces the Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill in Parliament. |

| Mid-2026 | The Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill are passed into law, and the transition period begins. This also marks the start of the transitional consenting period, which allows the benefits of the new system to be realised sooner. Statutory deadlines will be set for making new national instruments and plans. |

| Late 2026 / early 2027 | National policy direction under the new system will be finalised within nine months of the Bills becoming law. Mandatory national standards will be delivered in stages and aligned with council plan-making needs. |

| 2027 to 2028 |

Councils notify regional spatial plans within 15 months of the Bills becoming law. Councils decide regional spatial plans within six months of notifying them. |

| 2028 to 2029 |

Natural environment plans and land-use plans are notified within nine months of regional spatial plan decisions. The transition period ends via an Order in Council once all plans have been notified. All notified plans have legal effect, and the full new system is ‘switched on’. Consenting begins under the full new system. Councils decide land-use plans and natural environment plans within 12 months of notifying them. |

During the transition period, a transitional consenting framework will be used. The framework will allow new national instruments to have impact sooner, even while councils go through the process of updating their plans into the new system.

RMA plans will stay in place until the new system takes over. Ten-year reviews and national planning standards will remain on hold during the transition. Changes to RMA plans won’t go ahead unless they’ve been approved to continue.

Existing consents (including those granted during transition) will be valid under their current terms unless they’re due to expire during the transition, in which case they will be extended. Applications will be assessed under the rules in place when they are lodged. Section 124 protections will continue, so consent holders can keep operating under expired consents while new ones are being processed. Rules for changing or reviewing consents (sections 127 and 128) will still apply, based on the system in place at the time.

Consents that expire between when the new laws take effect and 12 months after the switchover on the ‘specified transition date’ will automatically be extended to 24 months after the specified transition date. These consent holders can either apply early under the transitional process or wait for the new system to begin.

Better planning for a better New Zealand

December 2025

© Ministry for the Environment