Te Pūnaha Whakahaere Rauemi o Anamata: Tirowhānui Our Future Resource Management System: Overview

'Our Future Resource Management System' provides an overview of the proposed new resource management system that will replace the Resource Management Act 1991 with three new Acts. The document aims to support an understanding of what is being proposed and to encourage all interested parties to make a submission on the Natural and Built Environment Bill and the Spatial Planning Bill, introduced to Parliament in November 2022.

'Our Future Resource Management System' provides an overview of the proposed new resource management system that will replace the Resource Management Act 1991 with three new Acts. The document aims to support an understanding of what is being proposed and to encourage all interested parties to make a submission on the Natural and Built Environment Bill and the Spatial Planning Bill, introduced to Parliament in November 2022.

Helping understand our future resource management system

In February 2021, the Government announced it would reform the resource

management system by replacing the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA)

with three new Acts:

This process is referred to as the resource management system reform in this document.

The proposed new system will:

This document provides an overview of the future resource management system, including its key components. It aims to support understanding of what is proposed and to encourage all interested parties to make a submission on the Natural and Built Environment Bill and the Spatial Planning Bill, which were introduced to Parliament in November 2022.

This document does not cover the Climate Adaptation Act. Public consultation on the early policy ideas for the CAA took place alongside the National Adaptation Plan consultation, which occurred in mid-2022 under the Climate Change Response Act 2002. It is expected that a Bill for the CAA will be introduced to Parliament in 2023.

Part One provides an overview of the reform process.

Part Two sets out a summary of the proposed future resource management system.

Part Three provides information on transitioning to the new system.

When this document refers to “the Minister”, it means the Minister/s responsible for the administration of the SPA and the NBA. This would currently be the Minister for the Environment

Parliament’s decisions affect all New Zealanders. You can have your say by making a submission on the new resource management system bills (once they are at select committee), at Make a submission.

To make a submission, select an item from the “Make a submission” tab and complete the form. You can also read the How to make a submission guide.

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is Aotearoa New Zealand’s main law governing how people interact with natural resources. As well as managing air, soil, freshwater and the coastal marine area, the RMA regulates land use, the provision of infrastructure and the allocation of scarce resources.

There is broad consensus that the current resource management system, introduced through the RMA 31 years ago, has not adequately protected the natural environment, nor enabled housing or development where needed. Challenges in the current system include:

In 2019, the Government commissioned an expert review of the resource management system, led by former Court of Appeal Judge Hon Tony Randerson KC. This was the most significant, broad-ranging and inclusive review since the RMA was enacted. The review was primarily focused on the RMA, its interface with other specific legislation, and a new role for regional spatial planning. The review consulted widely with local government, the private sector, Māori and other stakeholders.

The Randerson Panel’s report, New Directions for Resource Management in New Zealand 3 identified similar issues to those found in previous reviews of the resource management system; including reviews by the Productivity Commission in 2017 4, the Environmental Defence Society in 2018 5 and the Waitangi Tribunal from 1993–2020.6 The panel’s recommendations have provided a strong platform for change.

In February 2021, the Government announced it would repeal the RMA and – based on the recommendations of the Randerson Panel – enact three new Acts:

The Government set objectives for the future resource management system. These are to:

The key shifts from the current to the future resource management system are:

Policy development has closely followed the recommendations of the Randerson Panel. A Ministerial Oversight Group was convened with delegations from Cabinet to make decisions on the policy.

The development of the Spatial Planning Bill (SP Bill) has been overseen by a Spatial Planning Act Reform Board,7 consisting of chief executives from the Ministry for the Environment, Treasury, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, Department of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Transport and Department of Conservation, with the Ministry for Māori Crown Relations: Te Arawhiti as an observer.

The Ministry for the Environment (the Ministry) has led a joint effort across government to finalise the details of the Natural and Built Environment Bill (NBE Bill).

To ensure our policy development is robust, a wide range of stakeholders have been engaged on the proposed reforms.

This included public consultation by the Randerson Panel through its Issues and Options paper in 2019 and 2020, a select committee inquiry on an exposure draft of the NBE Bill in 2021, and targeted engagement on the key components of the future resource management system between November 2021 and March 2022.

The Ministry has undertaken ongoing regular engagement with local government through the Local Government Steering Group (Steering Group) and iwi/Māori collective groups. These groups have provided advice, tested policy and helped develop our thinking for implementation and transition to the new system.

We have also regularly engaged with key stakeholder groups, such as the Resource Management Reform Group (Environmental Defence Society (EDS), Property Council New Zealand, Infrastructure New Zealand, Employers and Manufacturers Association, and BusinessNZ), environmental NGOs (eg, EDS, Forest & Bird, Fish & Game New Zealand, Greenpeace Aotearoa and ECO), the Food and Fibre Forum, the New Zealand Planning Institute, the Resource Management Law Association and other key stakeholders.

In 2021, Parliament referred an exposure draft of the NBE Bill to Parliament’s Environment Committee. The inquiry conducted by this select committee allowed the public to get an early look at key parts of the proposed legislation.

The Environment Committee provided its report to Parliament in November 2021. Written and oral submissions were made on the exposure draft, with responses coming from hapū/iwi and Māori, local government, key sector stakeholders and the public. The exposure draft considered a range of environmental outcomes relating to the natural environment, cultural values, climate change and natural hazards, and well-functioning urban and rural areas.

The report also provided a list of ideas for making the resource management system efficient, proportionate, affordable and less complex.

Engagement with local government has been enhanced since 2021 with the establishment of the Local Government Steering Group (the Steering Group). The Steering Group comprises local government elected members and senior council executives. Its members come from a range of Aotearoa New Zealand’s councils, including territorial, regional and unitary councils from metropolitan, provincial and rural areas.

The Steering Group has met at least monthly since it was established and has provided independent advice on the key proposals for the new resource management system. The Minister for the Environment, Hon David Parker, meets with the group regularly. It has focused particularly on how the voice of local people can be heard in the new resource management system and has provided specific advice on this to inform the policy process. The Steering Group has also played a valuable role in advising how key

proposals are implemented.

The Steering Group will shift its focus to providing advice on transition to, and implementation of, the new resource management system and the National Planning Framework (NPF).

Engagement with local government has also included meetings with mayoral forums, elected representatives and senior local government staff. Meetings have been held with specific councils, including Auckland Council – for its experience in developing the Auckland Unitary Plan and Auckland Plan 2050 (a long-term spatial plan). The Ministry has also met regularly with Local Government New Zealand metropolitan, regional and rural and provincial sector groups, as well as Taituarā | Local Government Professionals Aotearoa.

Local government will continue to play the central role in the implementation of the new system.

The Ministry has undertaken ongoing engagement with two Māori leadership groups and their technical experts over the past year:

The Government has agreed to uphold the integrity, intent and effect of Tiriti settlements, takutai moana legislation commitments, existing joint management agreements and Mana Whakahono ā Rohe arrangements.

The RMA interfaces with over 70 Tiriti settlement arrangements. Engagement with post-settlement governance entities is underway to reach agreement on how to continue to honour these arrangements and those in other related legislation such as the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.

Engagement with relevant entities will also ensure the upholding of:>

The Crown is committed to upholding rights under the Marine and Coastal (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 and the Ngā Rohe Moana o Ngā Hapū o Ngāti Porou Act 2018 in the new resource management system. There are nearly 600 applications for recognition of customary interests to the High Court or directly to the Crown. These take the form of applications for an interest in land (customary marine title) or to have customary use rights protected (protected customary rights). Some customary marine title has now been recognised by the High Court and by the Crown in recognition agreements.

Customary marine title and protected customary rights include significant resource management rights for whānau, hapū and iwi – including the right to prepare a planning document and a permission right over some resource consents for customary marine title holders and resource consents not being able to be made if they will affect the ability of protected customary-rights holders to undertake a protected customary use right.

One of the Government’s objectives for the reform of the resource management system is to improve system efficiency and effectiveness, and reduce complexity, while retaining appropriate local democratic input. For development and infrastructure, this means unnecessary costs are removed and net benefits are maximised, with the new system delivering greater certainty, consistency and faster processes to providers.

To ensure this objective is achieved, the Ministry has established an external working group of practitioner experts to review the system (including processes and tools) to evaluate it constructively from an efficiency perspective and to identify further possible solutions.

The working group has membership drawn from a range of highly experienced resource management practitioners and the development sector. The group will provide a final report to the Ministry in mid-December 2022, and the report’s recommendations will inform the departmental report submitted to the select committee.

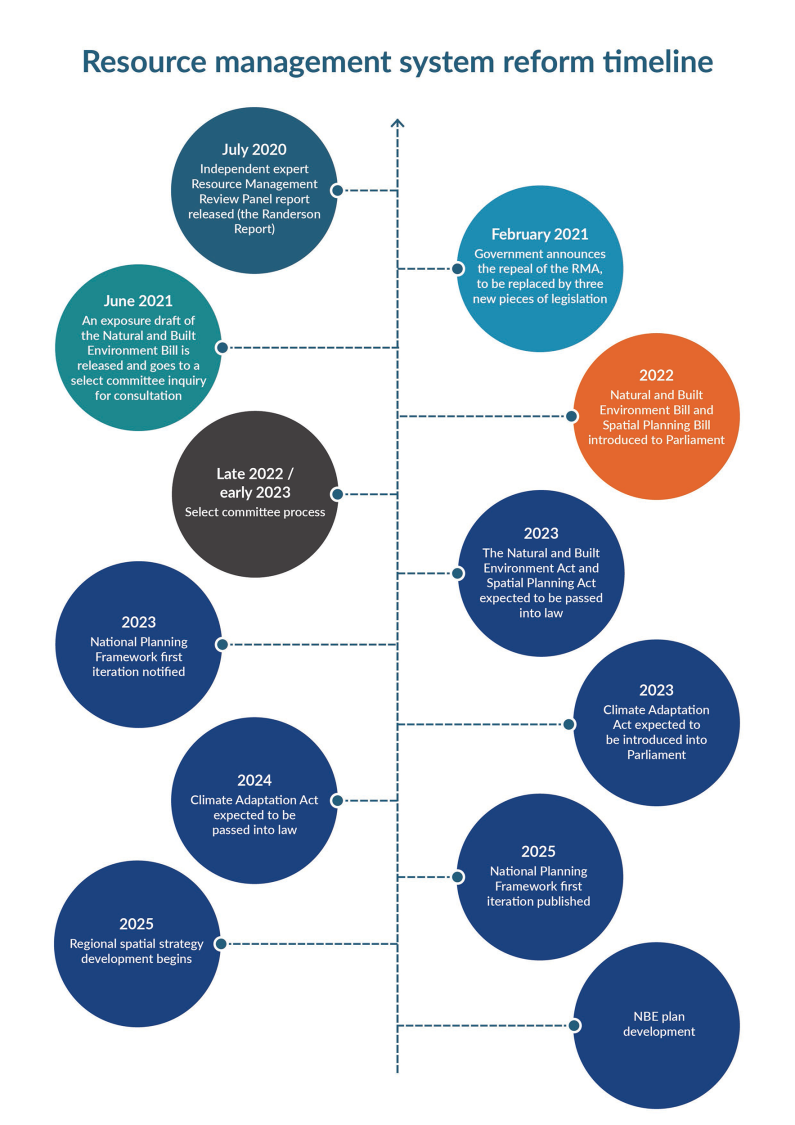

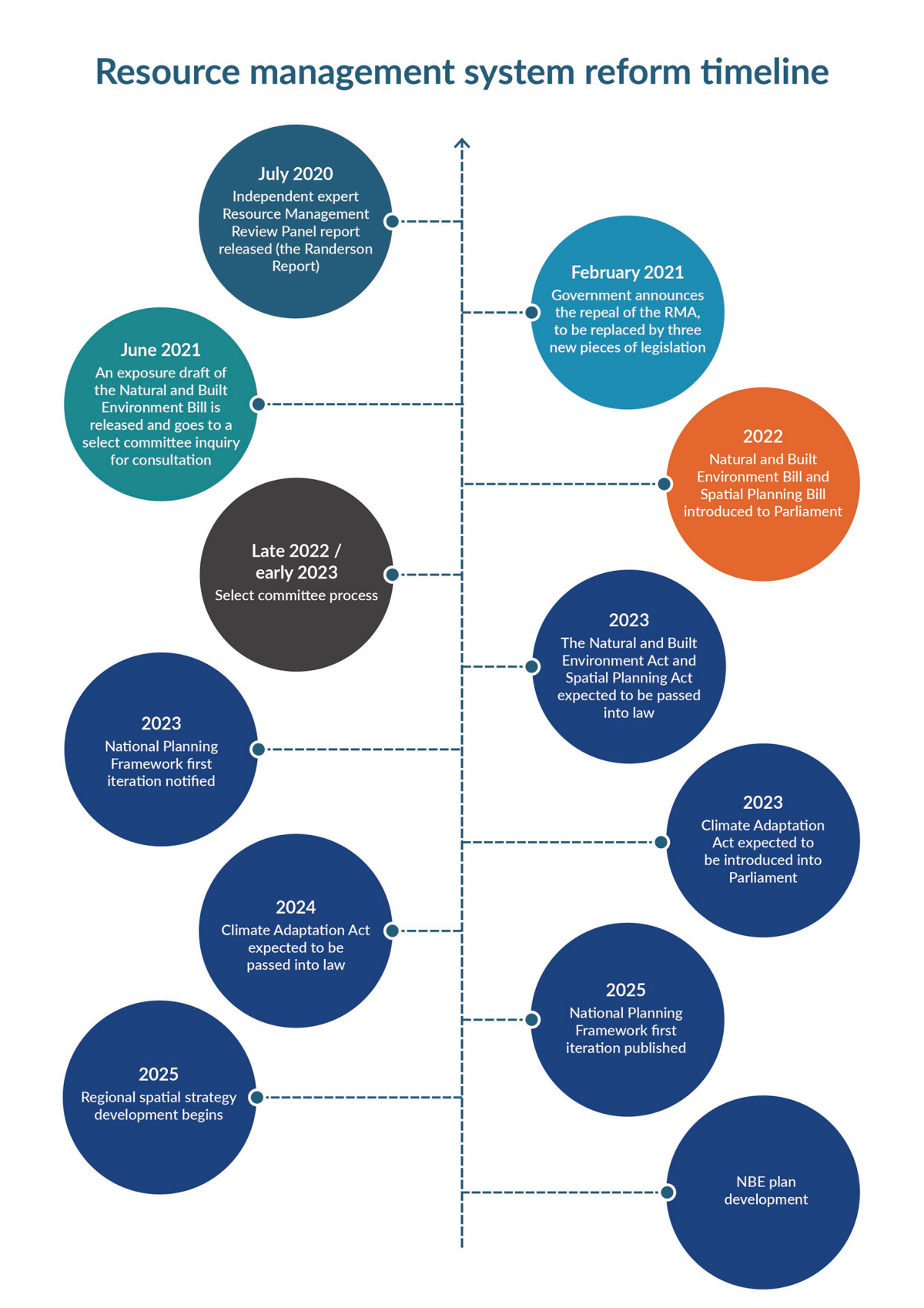

The Government intends to enact the NBA and SPA this parliamentary term. The Bills will go through a select committee process, where people can make submissions.

After the Bills are enacted, the next steps will be to develop the new system tools that are enabled by the new legislation. This includes the NPF, the RSS and the NBE plans. More about the transition and implementation of the new system can be found in Part 3 of this document.

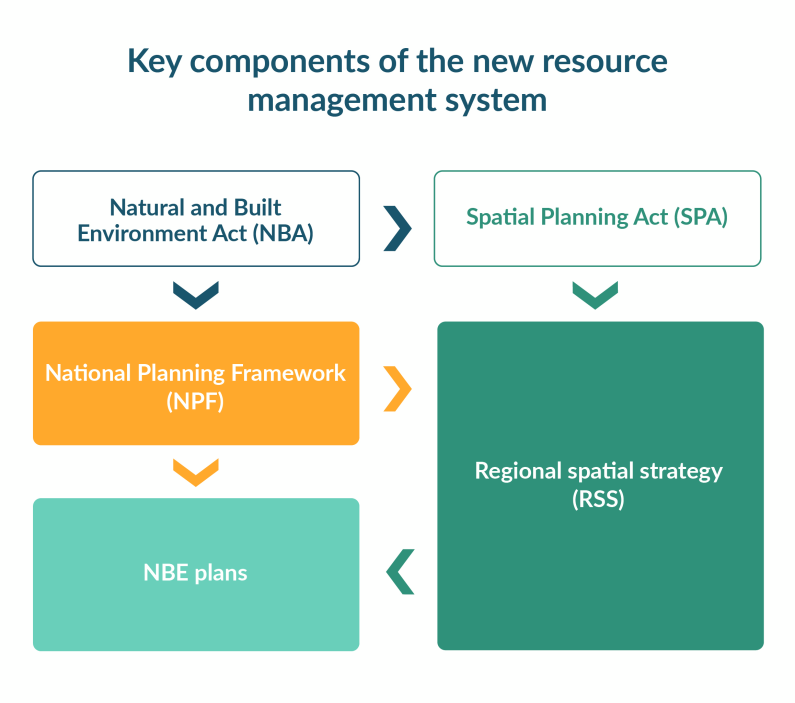

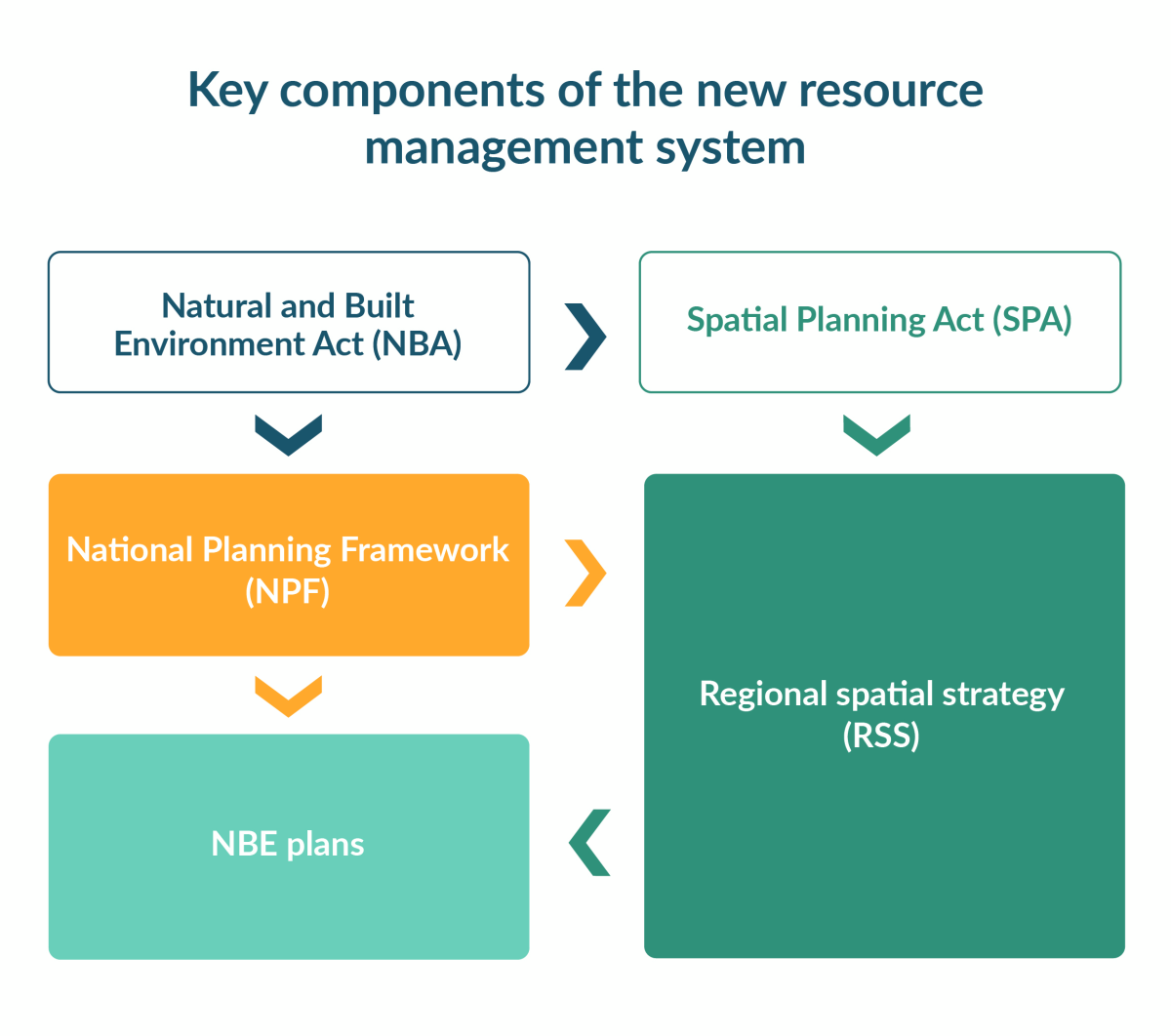

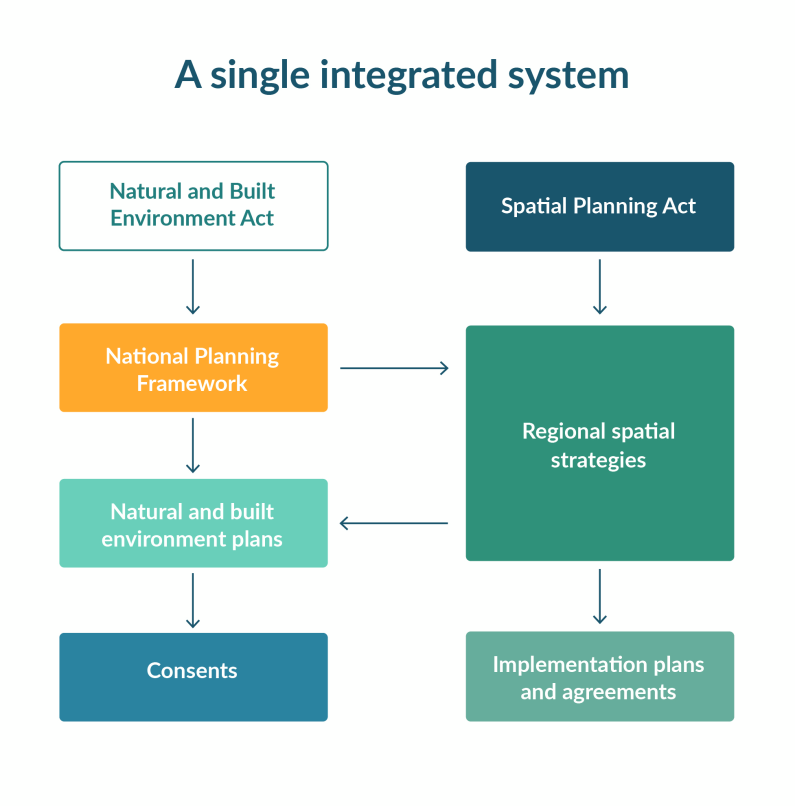

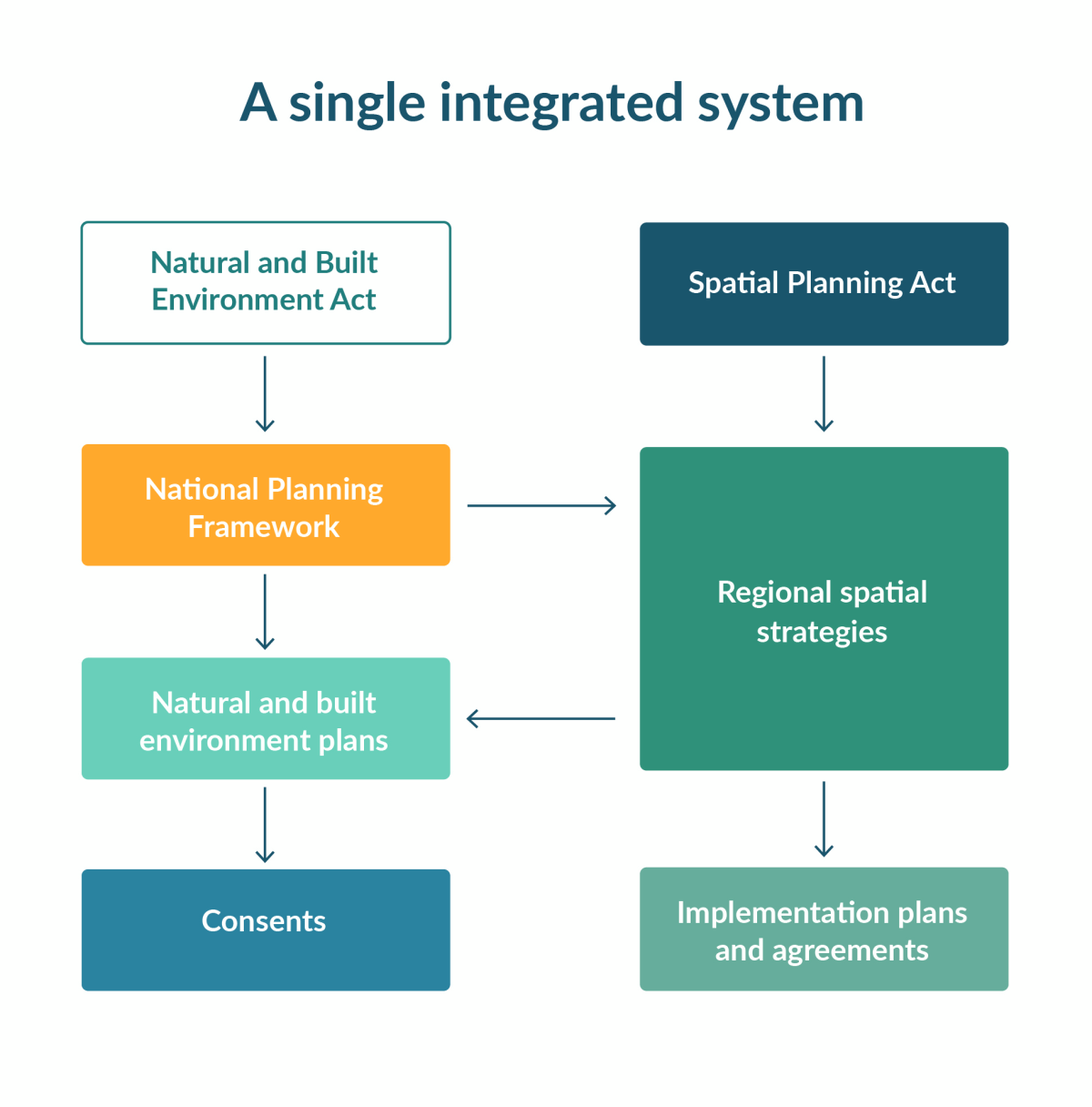

In the future resource management system, the Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA) and the Spatial Planning Act (SPA) will work in tandem to form the core part of the new resource management system. They will provide the legal framework for the planning, use and allocation of resources in natural and built environments across Aotearoa New Zealand.

The SPA will provide longer-term, spatially-based regional planning. It will introduce new requirements for a regional spatial strategy (RSS) and an implementation plan to integrate environment, land use, infrastructure, the coastal marine area and other planning.

Both Acts will require those exercising powers or functions under them to give effect to the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi (te Tiriti), as is the case under the Conservation Act 1987.

The NBA will be the primary legislation to replace the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). It will focus on protecting and restoring the environment, and on enabling land use that provides for growth and change while meeting environmental outcomes.

It will introduce a new National Planning Framework (NPF) to provide national policy direction on matters of national significance, environmental limits and targets, as well as direction on conflict resolution.

Each region will be required to develop a single RSS and natural and built environment plan (NBE plan) to guide land use and resource allocation. However, Nelson City and Tasman District will produce one combined RSS and one combined NBE plan.

The NBE Bill also introduces a revised resource consent system, which builds on the RMA consent system and introduces new process efficiencies.

The SPA aims to create a new function in the resource management system. It provides for mandatory spatial planning across all regions in Aotearoa New Zealand and requires central, regional and local governments and iwi/hapū and Māori to work together in the region.

The SPA will provide for RSS that set out the long-term (30–100 years), high-level strategic direction for each region, focusing on the big issues and opportunities they face.

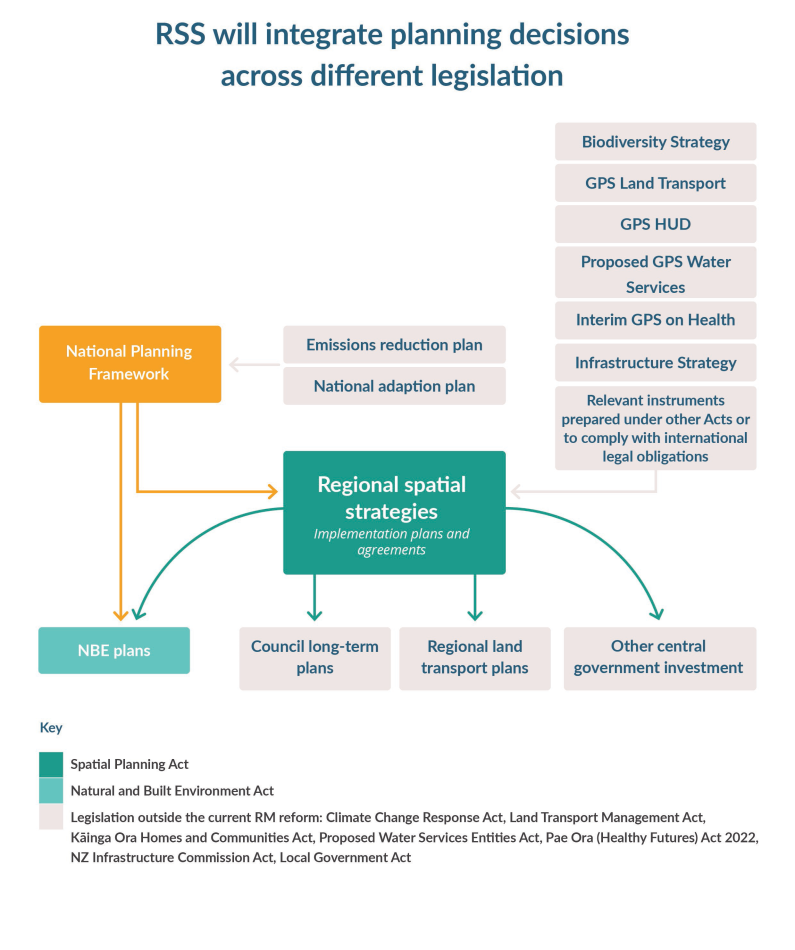

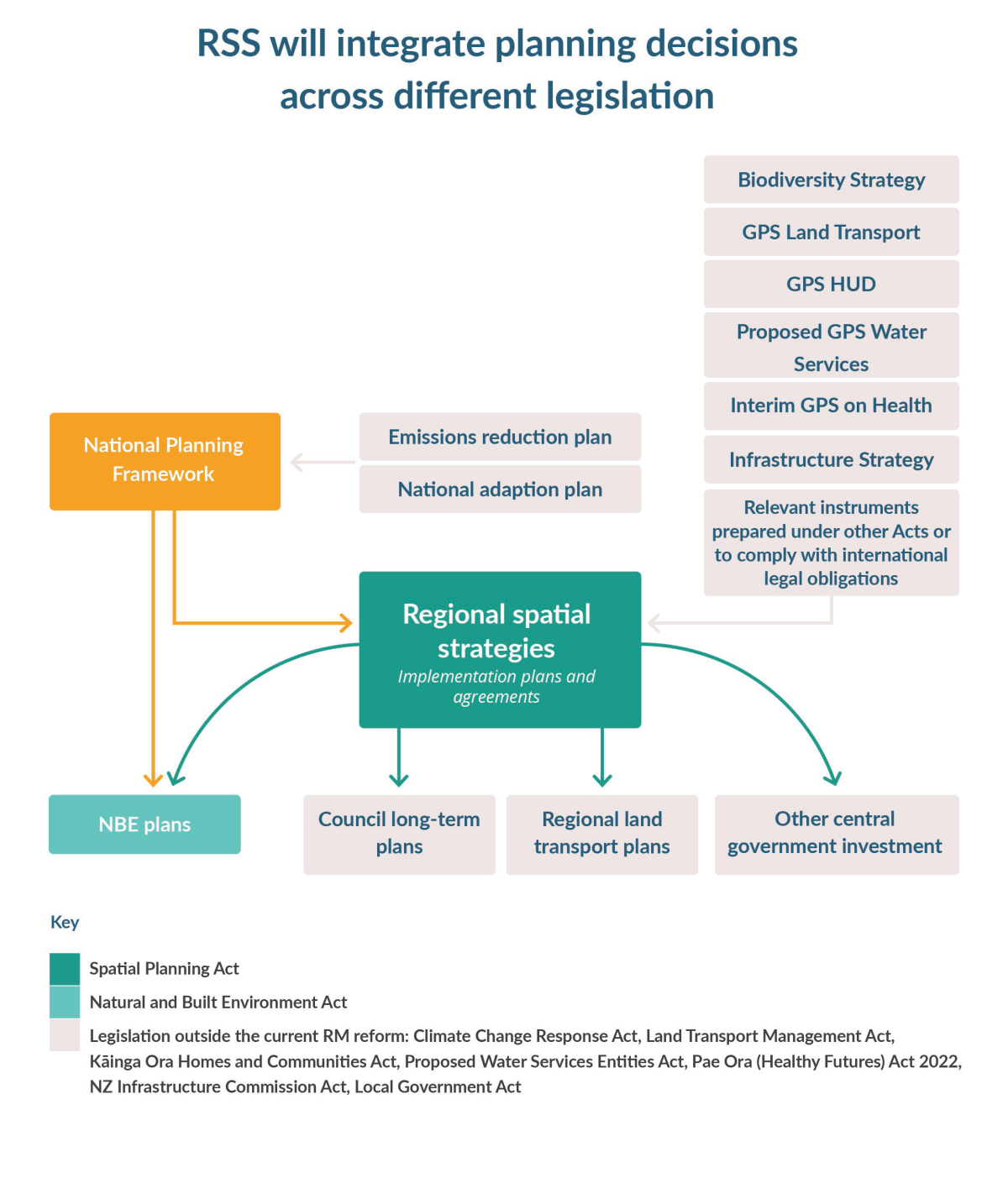

The SPA will also promote the integration of the statutory functions associated with the management of the natural and built environments across multiple Acts. These include the NBA, the Local Government Act 2002 and the Land Transport Management Act 2003. These Acts are important parts of the resource management system, and substantive changes to them are not proposed as part of this reform.

The NBA is the primary legislation to replace the RMA, and it will work with the SPA.

The NBA will integrate both land use and environmental protection. It sets out how the natural environment will be protected and enhanced and how development will be enabled within environmental limits.

Part 1 of the NBE Bill sets out the purpose, outcomes and principles. The purpose of the NBE Bill updates the RMA’s focus on sustainable management. It is an intergenerational environmental test for all New Zealanders. It draws on te Oranga o te Taiao, a te ao Māori concept that speaks to the health of the natural environment, the essential relationship between the health of the natural environment and its capacity to sustain life, and the interconnectedness of all parts of the environment

The NBA will also improve recognition of te ao Māori and the principles of te Tiriti.

The Government agreed with the Randerson Panel8 that the reforms should “give effect to” the principles of te Tiriti. This is what is proposed in the NBE and SP Bills.

The change in language – from “take into account” in the RMA to “give effect to” in the new system – ensures better recognition and implementation of the principles of te Tiriti. Guidance will be developed to help people understand what shifts in practice will be required.

The NBE Bill provides for strategic and regulatory direction from central government. It also includes implementation principles to guide how decisions are made – not just what they should seek to achieve.

Unlike the RMA, the NBE Bill specifies system outcomes that decision makers will be required to provide for natural and built environments. These outcomes include environmental protection and restoration; climate change mitigation and adaptation; well-functioning urban and rural areas, including for housing; the availability of highly productive land; public access to the coast, lakes and rivers; iwi, hapū and Māori interests; protection of customary rights; cultural heritage; and infrastructure provision. They guide the preparation of the NPF, NBE plans, and RSS under the SP Bill.

The NBE Bill will include a mandatory requirement for the Minister to set environmental limits for features of the natural environment to protect its ecological integrity and human health. These environmental limits will be either a minimum acceptable state for an aspect of the natural environment or a maximum amount of harm or stress that may be permitted to the natural environment.

A criticism of the RMA was that while there was a general obligation to avoid, remedy or mitigate adverse effects, there were no clear requirements to manage effects in ways that carried less risk of unintended outcomes. This led to less than satisfactory environmental outcomes.

The NBE Bill sets out an effects management framework for managing environmental effects on significant biodiversity areas and significant cultural heritage, unless an exemption applies or the NPF specifies a more stringent approach (eg, it may be appropriate to mandate avoidance for some effects). The NPF may also apply the framework to other resources.

The new effects management framework requires resource users to do what they can to avoid adverse effects before moving on to other options. These requirements are:

adverse effects must be avoided where practicable

any adverse effects that cannot be avoided must be minimised where practicable

after avoidance and minimisation, any remaining adverse effects must be remedied where practicable

after avoidance, minimisation and remediation, any remaining adverse effects must be offset where practicable

if adverse effects remain after avoidance, minimisation, remediation and offsetting to the extent practicable, then enhancement must be provided as redress; otherwise the activity must not proceed.

It is important to note that while this will be the general approach to adverse effects, there will be specific circumstances where either a more stringent or less stringent approach to managing adverse effects is appropriate. Those circumstances will be identified through the NBE Bill and NPF in the form of exceptions or additional restrictions.

In the new resource management system, the NPF will play an equivalent role to that of national direction under the RMA. It will be one of central government’s primary ways to influence and direct the resource management system.

The NPF will carry through, into a single integrated framework, the existing national direction in National Policy Statements (NPS), National Environmental Standards, the National Planning Standards and some section 360 regulations under the RMA. The NPF will provide direction and guidance on both RSS and NBE plans.

The NPF will provide direction on matters of national significance or, where national consistency is desirable, will provide direction on all the NBA environmental outcomes, including mandatory environmental limits that will protect ecological integrity and human health. The NPF will also include guidance on resolving conflicts.

The first NPF is the initial step to deliver national direction for the new resource management system. This will be in place by 2025, in time to inform the development of the first RSS. Particular regard must be given to maintaining consistency with the policy intent of the existing RMA national direction that is being consolidated into the first NPF.

We are currently developing the first NPF, which involves transitioning existing national direction into a combined document. This will include direction that has recently been developed, such as the NPS for Freshwater Management, the NPS on Urban Development, the RMA’s Medium Density Residential Standards, and the recently introduced NPS for Highly Productive Land.

National direction currently under development in the RMA system, such as the proposed NPS for Indigenous Biodiversity, would be incorporated into the new NPF.

A draft of the first version of the NPF will need to be ready for public consultation soon after the enactment of the NBA.

The intention is for the NPF to be amended during the transition period to provide further direction to NBE plans and as the need for more direction on nationally significant matters is identified.

The Minister will be responsible for establishing a board of inquiry to inquire into the proposed NPF. There will be an opportunity for the public to submit on it and to be heard.

The NPF will include an overarching layer that provides direction on resolving conflicts, and new national direction will be developed for:

identifying and mapping management units for limit setting

infrastructure

climate change and natural hazards

cultural heritage

outstanding natural features and landscapes

the relationship of iwi and hapū and the exercise of their kawa, tikanga and mātauranga in relation to their ancestral lands, water, sites, wāhi tapu, wāhi tūpuna and other taonga.

There will be a transition period (about 10 years) after the NBA and SPA are enacted until all new RSS and NBE plans are in force. During this time:

the first iteration of the NPF will be ready for the development of first RSS, with subsequent additions made in time to inform the development of first NBE plans

the RMA national direction will remain in force to continue directing RMA plans, policy statements and transitional decision making

powers under the RMA to develop and amend an existing national direction instrument will remain in force during the transition period, albeit with a requirement that newly developed RMA national direction will need to consider the desirability of consistency with the NBA

a new National Māori Entity will be established under the NBE Bill. It will monitor te Tiriti performance of the resource management system, input into the development of the NPF, provide advice to persons operating in the system and nominate members for the NPF boards of inquiry.

The NPF will be amended over time to respond to emerging issues and implement key government policy direction. The NPF must be reviewed at least once every nine years, with the ability for the Minister to review all or part of the NPF at more frequent intervals.

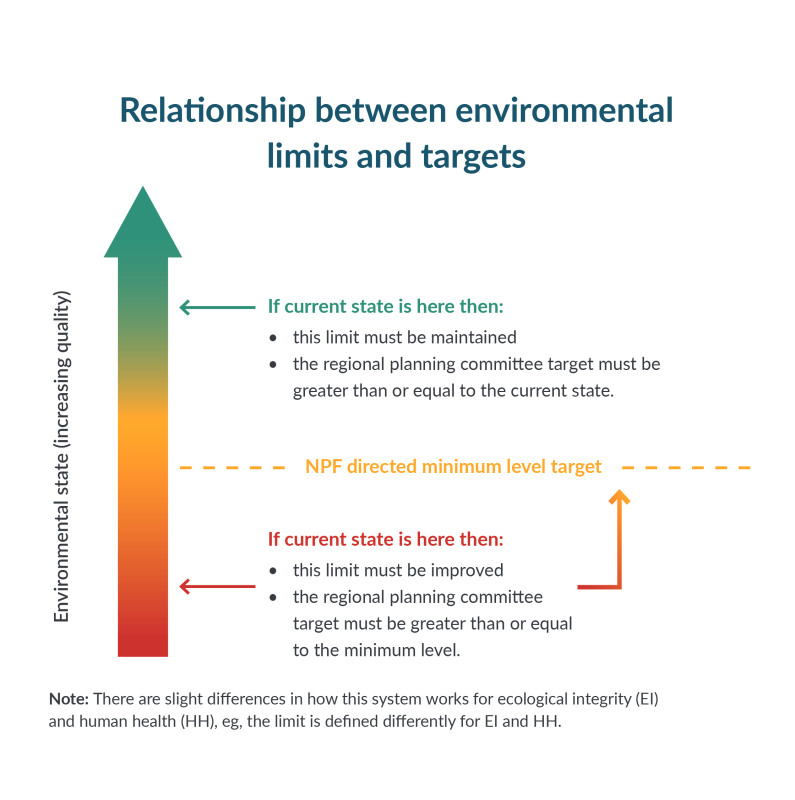

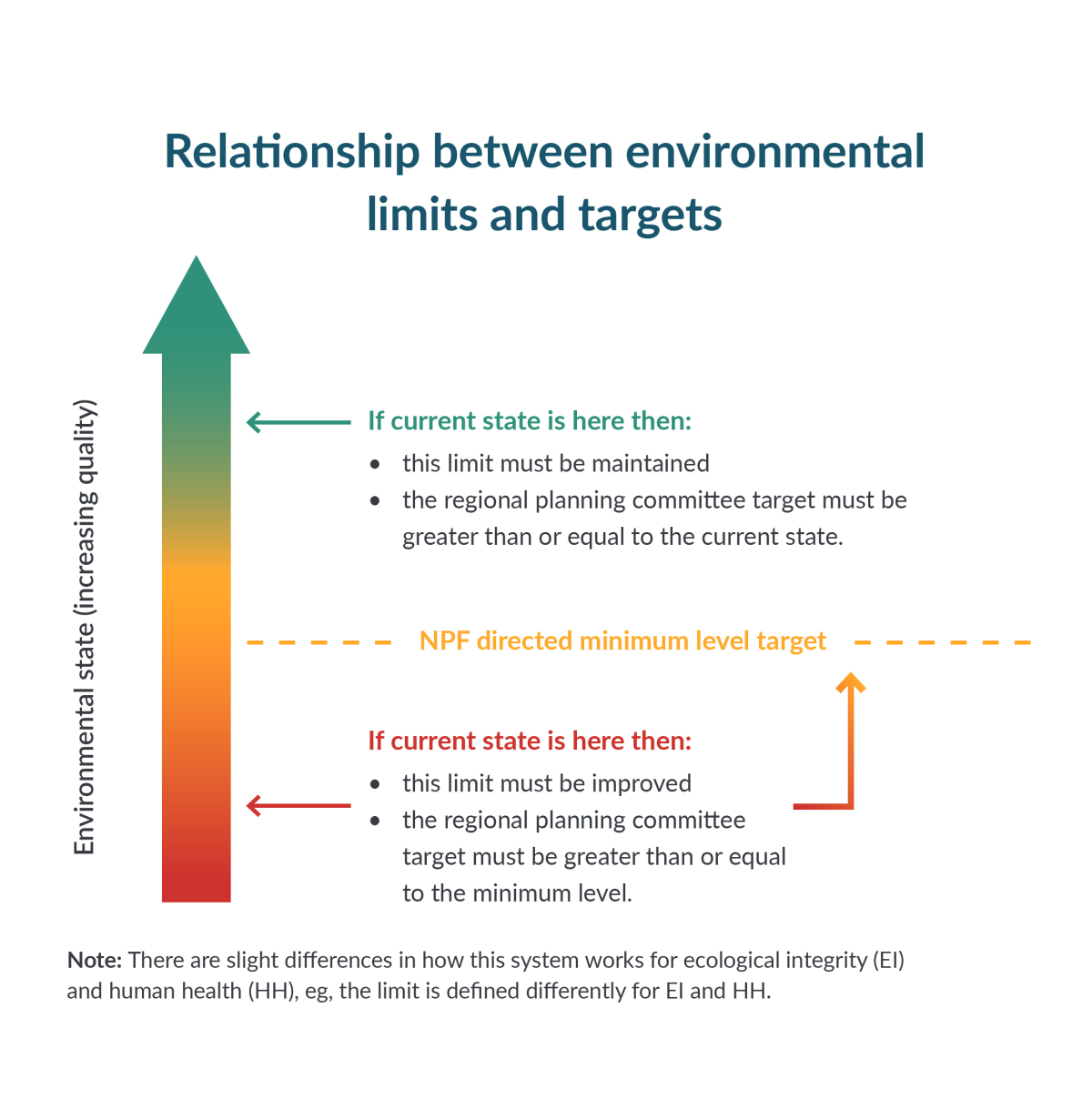

Environmental limits and targets are a primary means for the new resource management system to prevent further environmental degradation and drive environmental improvements.

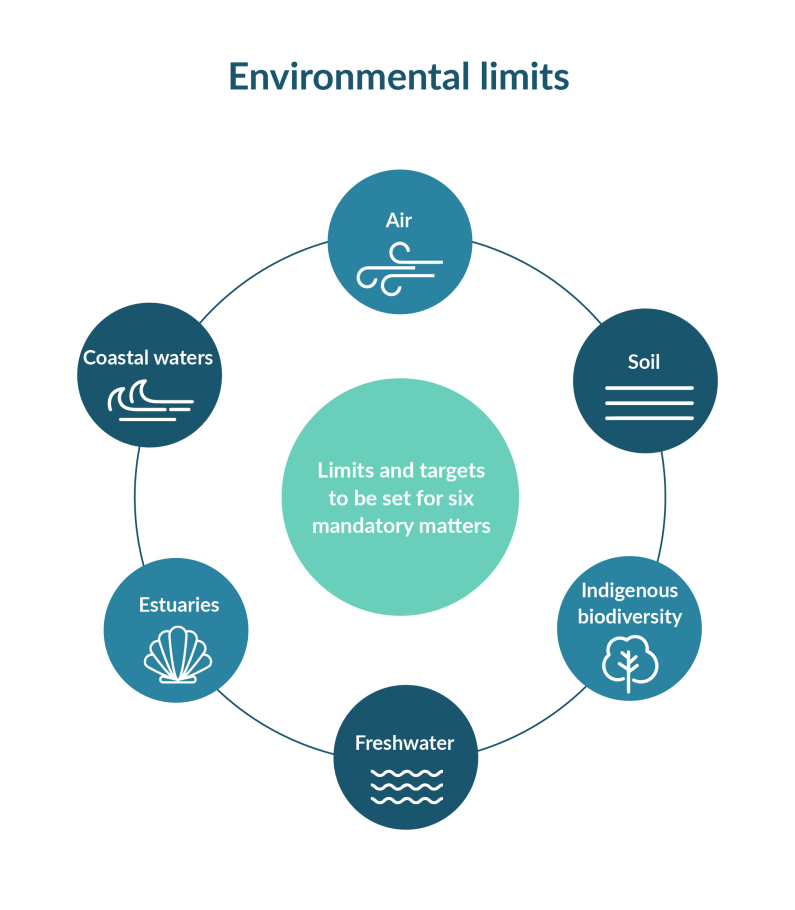

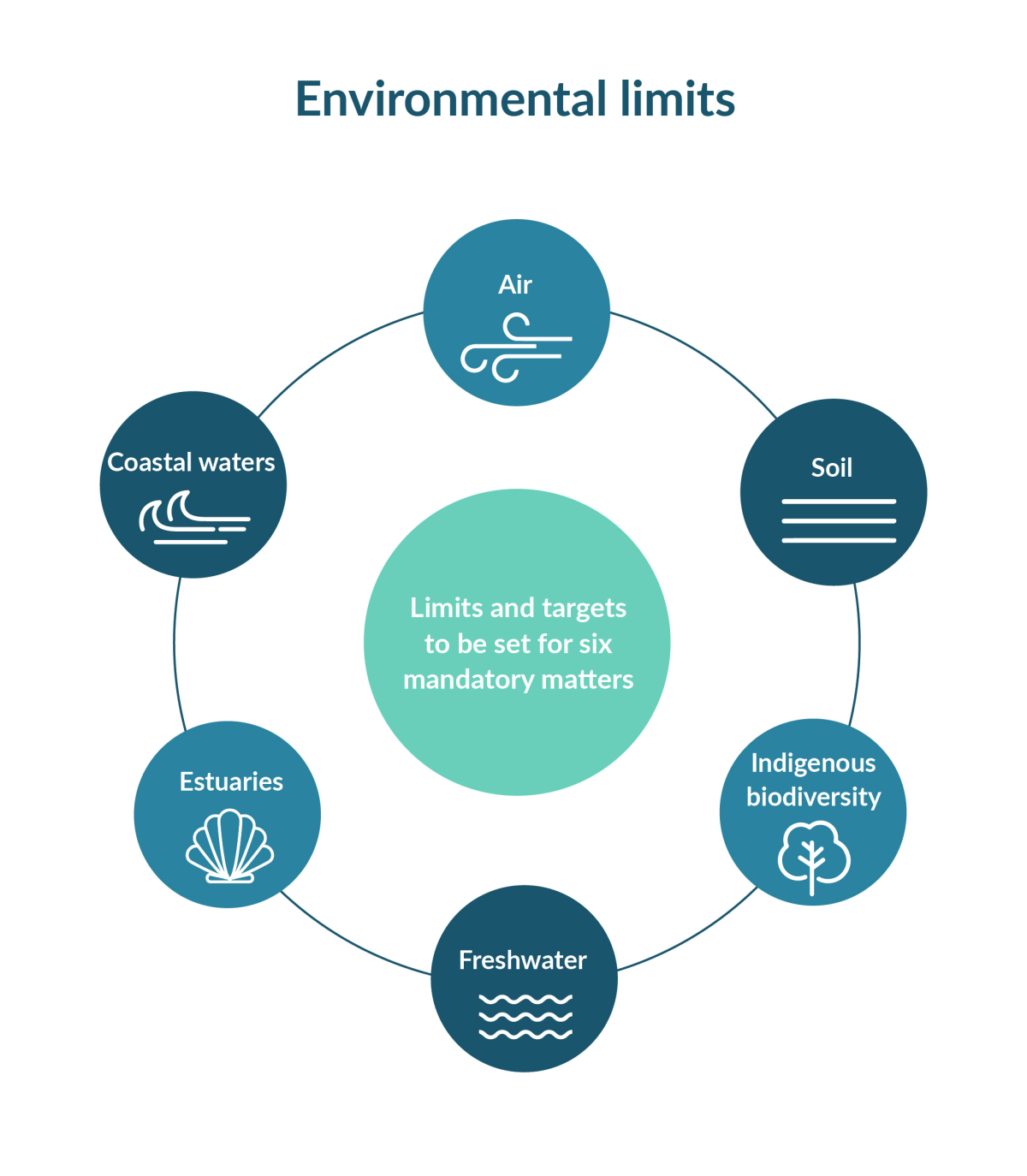

Limits and targets will be set across six mandatory matters: air, soil, indigenous biodiversity, freshwater, estuaries and coastal waters, and they may be set for other matters.

The purpose of environmental limits is to protect human health and to prevent the ecological integrity of the natural environment degrading from its current state.

Targets will be associated with limits to drive improvement of the natural environment. These will be mandatory and may be set nationally in the NPF or the NPF may provide for them to be set locally in NBE plans. In addition, discretionary targets associated with outcomes may be set by the Minister, or the Minister may direct how they are to be set by a planning committee.

The NBE Bill enables the NPF to set out:

what aspects of the natural environment to measure, across the mandatory matters for ecological integrity and human health

how these aspects are to be measured

any requirements for how to set limits or targets and their levels in plans, which may include minimum level targets

any direction on how the aspects are to be managed (that is, to defend limits and achieve targets).

Where the current state of ecological integrity is unacceptably degraded, the NPF will set out a minimum level target, and plans must include how targets are to be achieved. This is similar to the “national bottom lines” approach in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020. Minimum level targets that already exist in current national direction (such as those in the NPS-FM) will be carried over.

The new limits and targets will also be set within “management units”. These must be set at an appropriate spatial scale to ensure no loss of ecological integrity and the protection of human health.

The NBE Bill requires a panel to assess and review the science and evidence, including mātauranga, underpinning potential limits and targets before the NPF is referred to a board of inquiry.

Where a regional planning committee (RPC) identifies, during the preparation of an NBE plan or RSS, that various social, cultural and economic goals will not be met without undermining limits for ecological integrity, the committee may apply for an exemption application may be made to the Minister. Exemptions will not be available at the consenting stage to avoid unplanned degradation from cumulative ad hoc decision making on individual development applications. Exemptions must be planned for proactively and strategically and after considering options for complying with the limit.

The types of matters the Minister must consider include:

whether an exemption, from an environmental limit, results in the least possible net loss of ecological integrity that is compatible with the activity proposed

whether the activity provides public benefits that justify any loss of ecological integrity

the time limit that an exemption must be subject to and any conditions to be imposed.

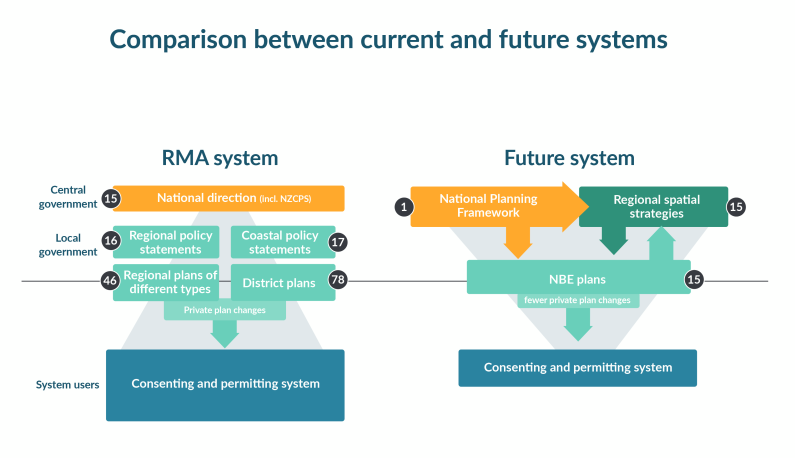

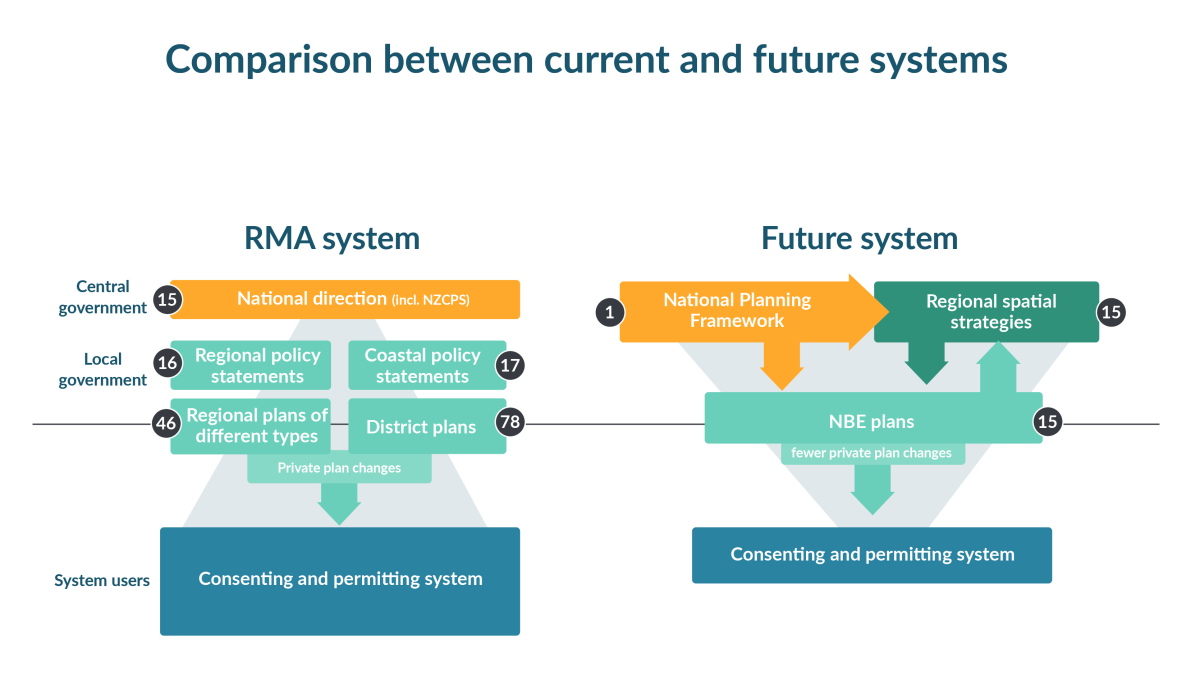

Under the reformed system, the RPC will develop one RSS and one NBE plan for each region. This will reduce the existing 100 regional policy statements, coastal policy statements and regional and district plans to 15 RSS and 15 NBE plans, simplifying and improving the integration of the system.

The reformed resource management system will be “front loaded”, covering more planning scenarios, and will be more directive and certain than the current system under the RMA.

RSS will play a critical role in driving and enabling change across the resource management and funding systems. The purpose of the RSS is to provide long-term, high-level and strategic direction for integrated spatial planning in a region. It will set out a vision and objectives to guide the region over the next 30-plus years, which will be expressed spatially, accompanied by priority actions that will help turn the vision into reality.

RSS will be developed by RPC. The strategies will be required to identify at a high level and (where appropriate) map spatially:

areas that may require protection, restoration or enhancement of the natural environment (this will uphold te Oranga o te Taiao)

areas of cultural heritage and areas with resources that are of significance to Māori

areas subject to constraints (eg, natural hazards and areas impacted by climate change)

areas appropriate for housing and development

areas where significant land-use change is required (eg, to meet growth needs or comply with environmental limits)

indicative locations for future infrastructure corridors and strategic sites.

RSS are required to be consistent with or, if specified, give effect to the NPF.

Depending on the issue, the NPF may provide high-level and principle-based direction or may require the RSS to take specific actions or use particular methods (eg, mapping methods to support robustness and consistency across regions).

In developing RSS, RPC will also be required to have particular regard to relevant Government Policy Statements (eg, Government Policy Statement on Land Transport [GPS] 2021, Government Policy Statement on Housing and Urban Development [GPS-HUD], Government Policy Statement on Health [2022 (interim)], and a proposed future Government Policy Statement on Water Services, and have regard to the Minister’s response to the 30-year Rautaki Hanganga o Aotearoa, New Zealand Infrastructure Strategy 2022–2052, along with other strategies such as the Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy.

To drive and enable change across the system, the SPA requires that an RSS be accompanied by an implementation plan.

Implementation plans will be high-level plans for delivering priority actions in an RSS. These will be approved by an RPC in consultation with delivery partners – ie, those who have an action under an RSS. This could be central government, local government, iwi, Māori or the private sector. The plan will identify the key actions that delivery partners will take to implement the RSS, as well as the approach to monitoring and reporting on delivery.

The RPC must review the implementation plan every three years or when there is a significant change to the RSS.

The delivery partners may also decide to enter into optional implementation agreements to give effect to specific projects or actions identified in the implementation plan. Together, both implementation plans and implementation agreements will provide a collaborative mechanism to link projects and programmes to funding streams from different sources, connect key parties (public, partially privatised and private) and sequence infrastructure provision in a logical way.

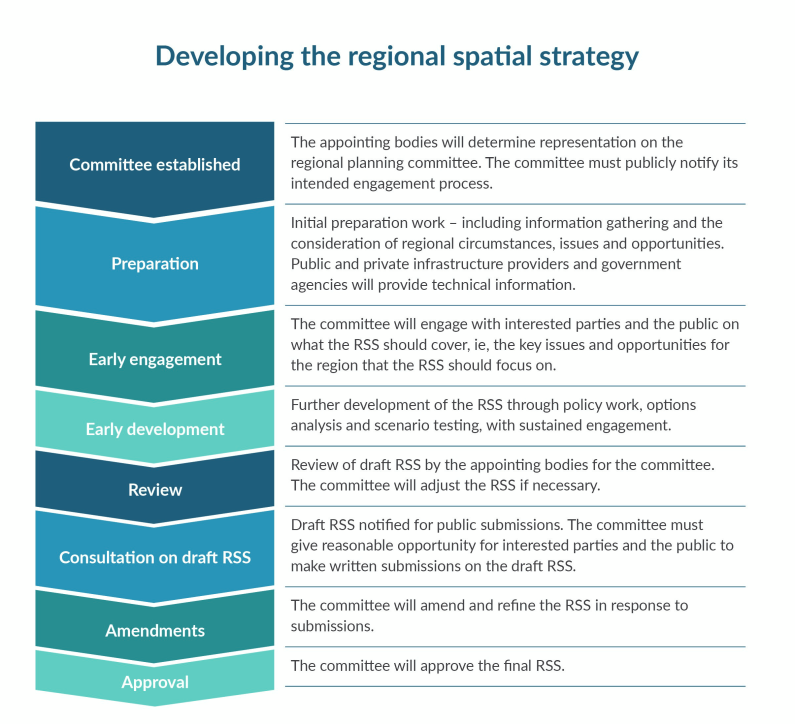

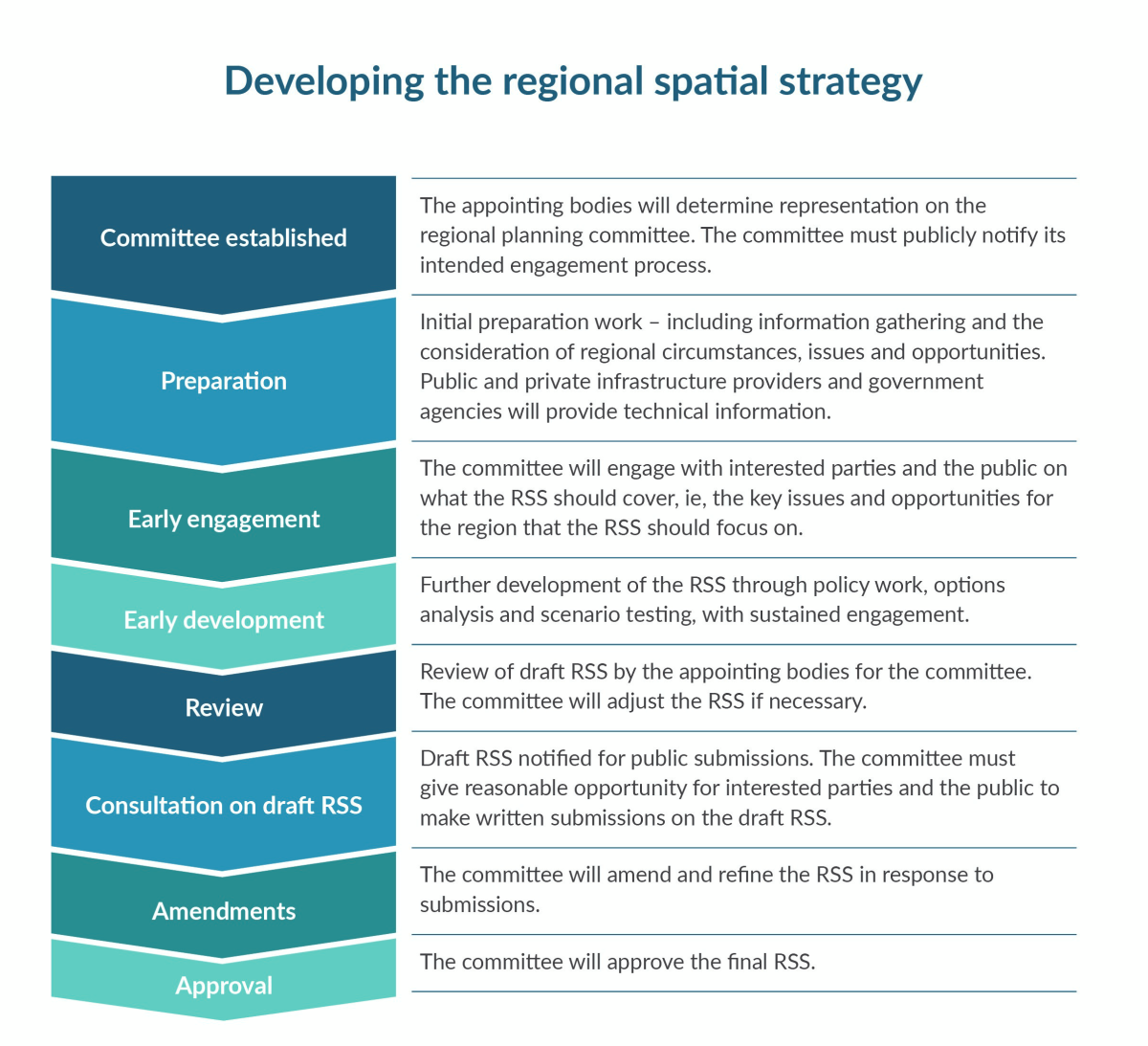

Each RPC will develop and approve the RSS. The SPA provides the RPC with significant flexibility to design its own engagement approach with the community and key sector groups.

The RPC must publicly notify its intended engagement process. Following this, the committee will undertake early engagement with interested parties and the public on what the RSS should cover and the key issues and opportunities for the region that the RSS should focus on. A draft RSS will then be developed, with options, analyses and scenarios to test with the community. If requested by an appointing body, the draft RSS will be provided to that body to review before being notified for submissions.

In doing this work, the RPC will need to gather and consider robust information, then create a draft evaluation report that sets out the key evidence used, and scenarios or options considered, and the reasons for their choices when deciding what to put in the draft RSS. The evaluation report will be finalised at the end of the process, to provide a permanent record relating to evidence used and decisions made.

The draft RSS will be notified for public submissions, with amendments and refinements made based on this feedback. Decisions will be made by consensus, but there will be a dispute resolution process if this cannot be reached.

RSS will be reviewed every nine years. The RPC will need to adopt a policy outlining what they deem to be a “significant change” that would trigger an earlier review of the RSS. If the review identifies a need for substantial changes, the RSS will be amended using a new public process. Out-of-cycle reviews of an RSS may be directed by the Minister or through the NPF.

Natural and built environment (NBE plans) will provide a framework for managing the natural and built environment for each region. The plans will be outcomes-focused, that is, focused on the results regions want to achieve and developed to give effect to the NPF and be consistent with the RSS.

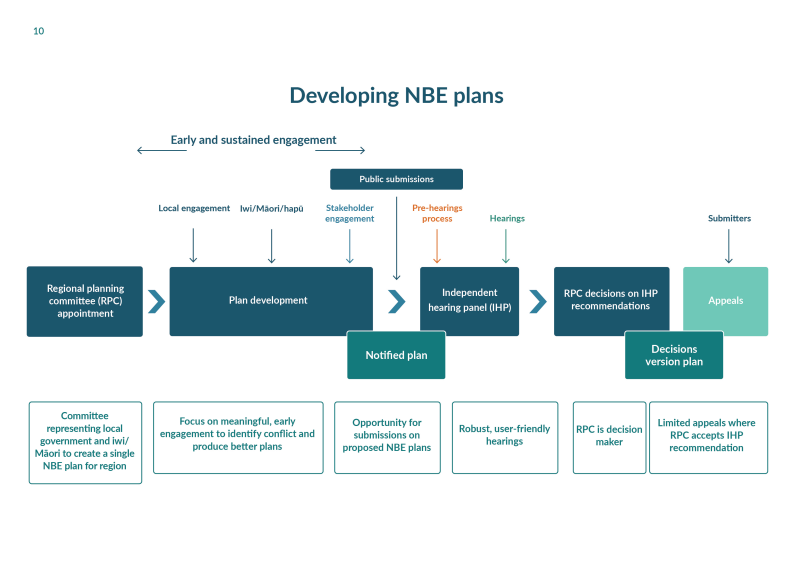

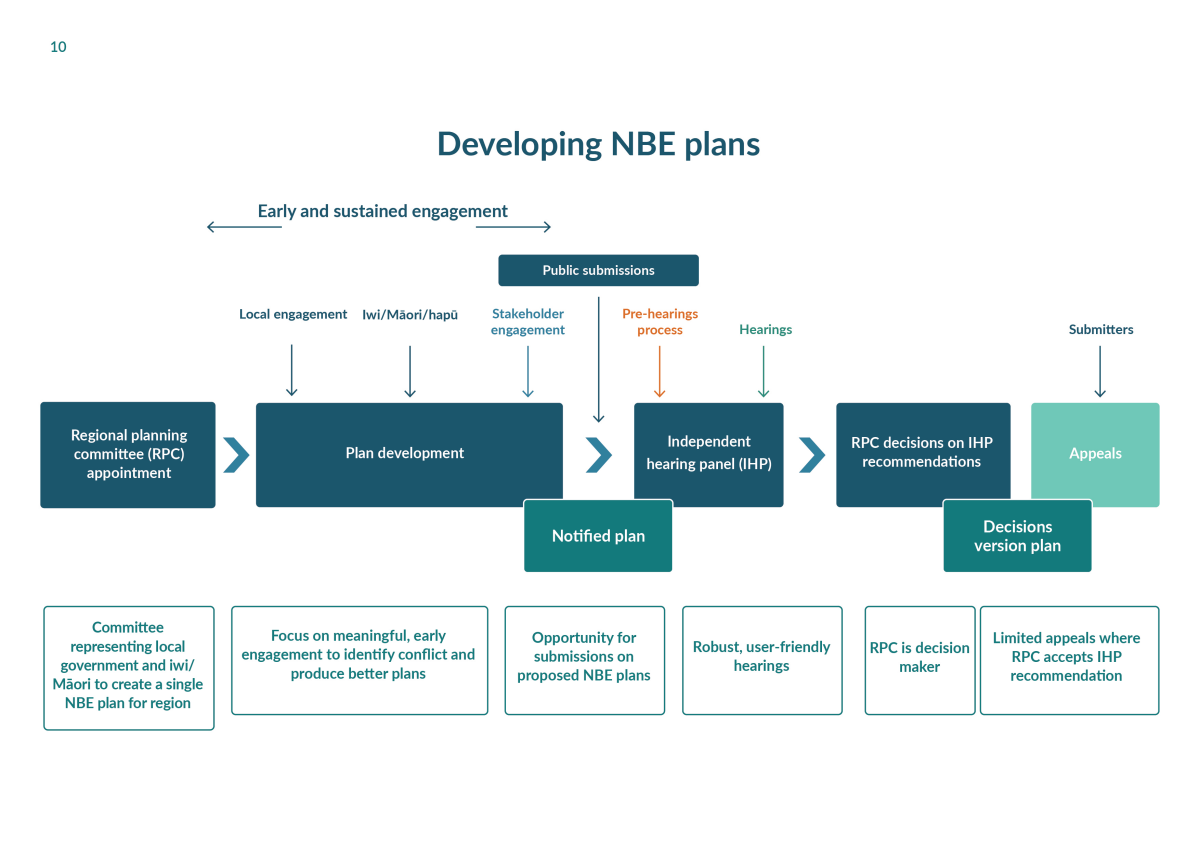

The existing regional policy statement and regional and district plans will be replaced by one NBE plan for each region. This consolidation will bring significant efficiencies into the system by providing greater consistency across a region. NBE plans will be prepared by an RPC for each region comprising local government and Māori members with support from a secretariat.

NBE plan development follows the development of an RSS. The RPC will seek input into the NBE plan from local communities, hapū/iwi and Māori; those with infrastructure and development interests; and stakeholders. This is expected to take two years.

NBE plans are intended to have a strong local voice. Early engagement will be encouraged, and parties who wish to contribute to the plan development process can register to engage in the process.

Statements of community outcomes (SCOs) and statements of regional environmental outcomes (SREOs) are proposed as voluntary instruments to provide local authorities with a mechanism to directly input local voices into NBE plans. SCOs are to be prepared by territorial authorities and will express the views of a region, district or local community. SREOs are proposed to address any significant resource management issues faced by a region, district or local community and will be prepared by regional councils. RPC will be required to have regard to the SCO and the SREO in their decision making.

Hapū/iwi and Māori entities are intended to have an early and sustained role in plan development through engagement agreements.

A new feature of the plan development process is “enduring submissions”. Submissions raised through early engagement, but lodged before the formal notification of a plan, will hold weight in the plan hearings process like normal submissions.

Checks and balances will be built into the plan development process. The Ministry for the Environment (the Ministry) will have an auditing role, checking the draft plan for compliance with the NPF and with environmental limits and targets. Local authorities will also be able to review and comment on the draft plan before it is notified.

After the plan development phase is complete, the RPC has two further years to notify, hear and make decisions on an NBE plan. Any person or entity can make a submission. Submitters must provide full information and any supporting evidence when they file their submission. This is a significant change from the current system and is designed to increase process transparency, efficiency, and fairness.

The hearings process for NBE plans will be run by an Independent Hearing Panel (IHP) and will usually be chaired by an Environment Court judge. The hearings process is intended to be inquisitorial (investigation based) rather than adversarial (opposing positions). Alternative dispute resolution processes, pre-hearings and conferencing with experts and other mechanisms will be available to resolve or narrow disputes before hearings commence. There are limits on bringing new evidence to IHP hearings that was not provided with submissions, and parties cannot be cross-examined. The IHP must make its recommendations back to the RPC who are the decision makers on the NBE plan.

The robust IHP hearings process makes it appropriate to place limits on subsequent appeals. Where an IHP recommendation is accepted by the RPC, appeals are limited to points of law in the High Court. Where an IHP recommendation is rejected, merit-based appeals can be made to the Environment Court. There are limits on bringing any new evidence to the Environment Court that was not provided in the earlier IHP process

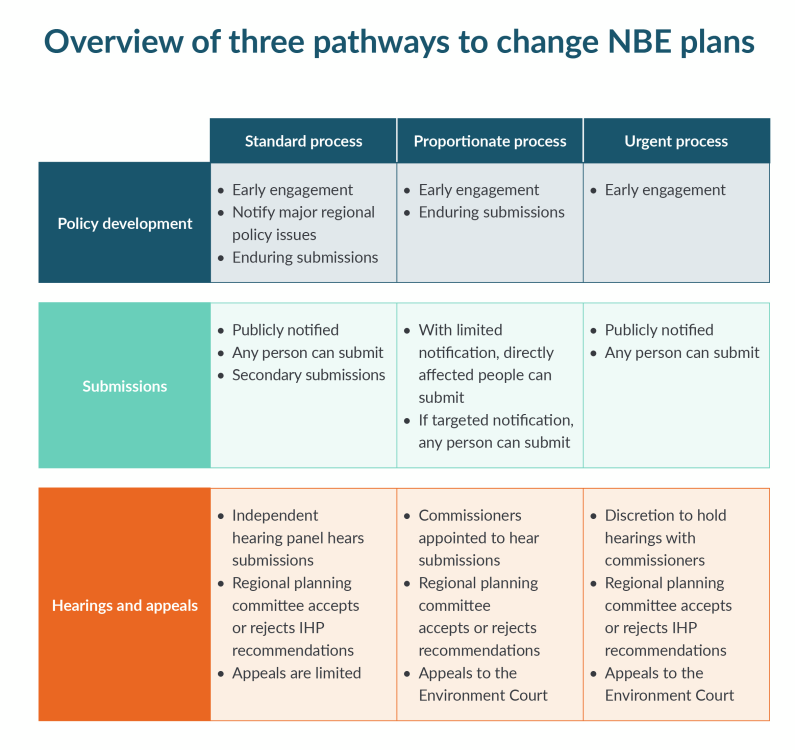

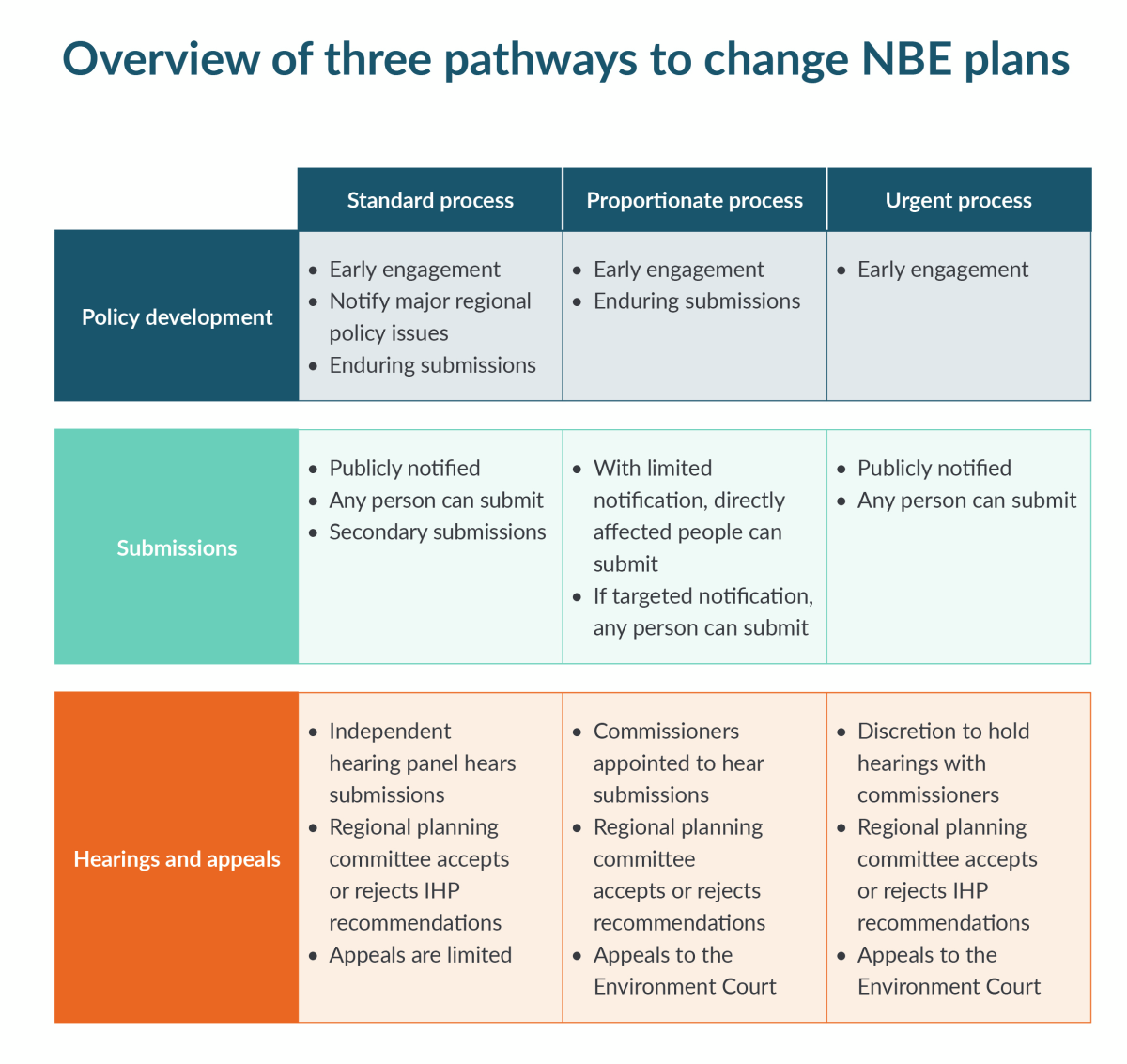

Each RPC will be responsible for reviewing and changing its own NBE plan. The committee, a local authority or any other party can initiate or request a change to an NBE plan. There are three pathways (see Figure 9) for undertaking plan changes, which are designed to respond to the scale and nature of the issues being considered.

Most plan changes will use the standard process, but less complex issues (such as local re-zoning, local centre planning or localised natural resource issues) can use a proportionate process. An urgent process will also be available, which is more expedient but subject to specific criteria, keeping the planning system flexible and responsive.

Private plan changes (now “independent plan changes”) are provided for in the NBE Bill. The NBE Bill sets requirements for requested independent plan changes, including a requirement for the change to be consistent with the region’s RSS. If the requirements are not met, local authorities can reject the request before it is passed on to the RPC.

The NBE Bill requires local authorities to report to the RPC every three years, identifying any issues, opportunities or outcomes the NBE plan should address. The RPC will then use this information to produce a three-year work programme to implement recommendations. Every nine years, the RPC must also reassess its full plan to consider whether it continues to meet the requirements of the Act.

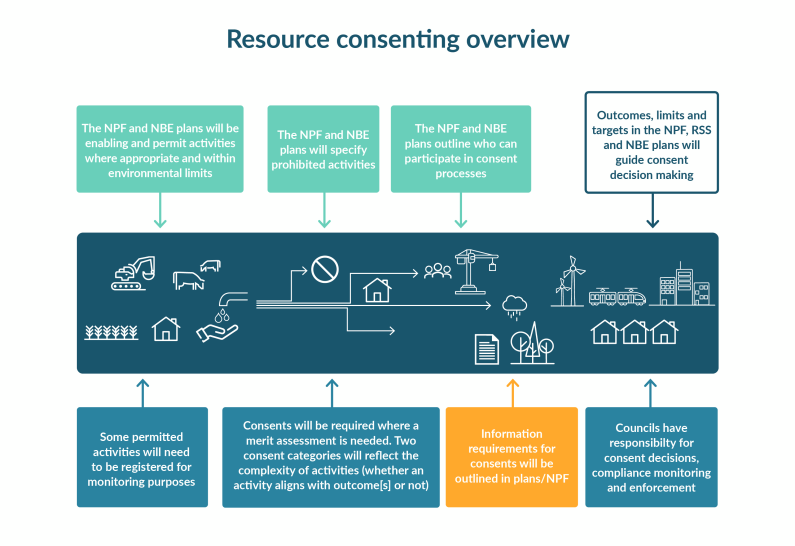

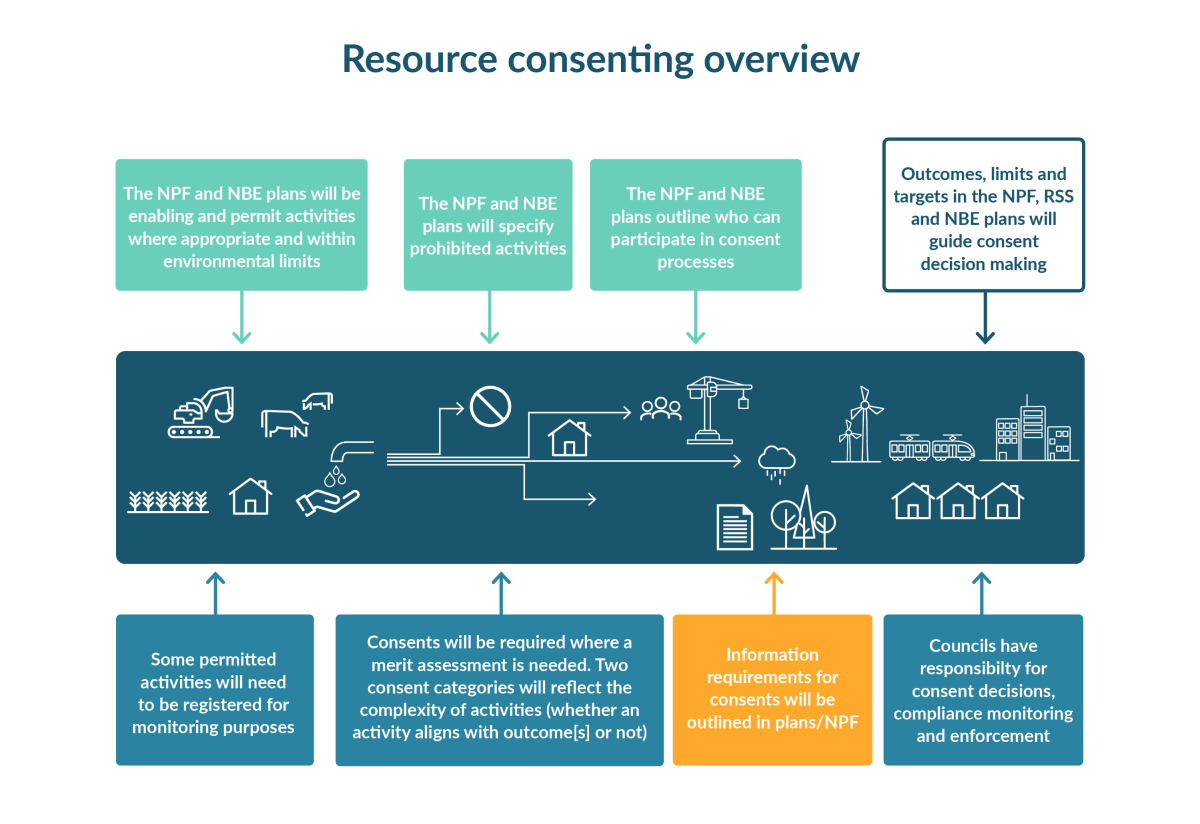

Resource consents will continue to be the primary land-use or resource-allocation approval method under the new resource management system.

The new consent system will provide more certainty and be more efficient to help reduce costs for users and decision makers. The NPF and NBE plans will enable more activities without a resource consent, where they are appropriate and within environmental limits. This will focus resource consent applications on activities with less certain outcomes and higher potential for adverse effects.

NBE plans and the NPF will guide consent requirements for activities within a region. The type of consents required will be the same as under the RMA, including:

land-use consents

subdivision consents

coastal permits

water permits

discharge permits.

Councils will be responsible for managing and making decisions for most consent applications. Some applications will be eligible to be processed under alternative consenting pathways, such as through a board of inquiry. These applications will have unique characteristics where they may be nationally significant, subject to higher risks of appeals or contain community benefits requiring more streamlined processes.

Together with the NPF, NBE plans will identify activities in one of four categories.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Permitted | Activities where positive and adverse effects are known, where environmental outcomes are met and where no consent is required |

| Controlled | Activities where potential effects are generally known and where tailored management of effects is required to meet environmental outcomes. There will be limited discretion to decline consents. |

| Discretionary | Activities that are less appropriate or unanticipated, with effects that are less known or that may breach limits or not meet environmental outcomes. |

| Prohibited | Activities with significant adverse effects and that would not meet outcomes, where no consents can be applied for. |

The NPF or NBE plans may permit an activity with or without requirements. Such requirements could include seeking a person’s written approval or obtaining an environmental management plan certified by a suitably qualified person. The NPF or NBE plan will direct some of these permitted activities to be registered with councils for monitoring purposes.

Resource consents will be required for controlled and discretionary activities to enable assessment of these applications to be considered on their merits. Assessment will be tailored to the complexity of the application and potential outcomes and effects.

A fast-track pathway for specified housing and infrastructure is proposed as an alternative process to general consenting and notice of requirement processes proposed under the NBE Bill, and replaces the fast-track consenting process under the COVID-19 Recovery (Fast-track Consenting) Act 2020.

For a project to use this pathway, it must meet the eligibility criteria in the NBE Bill and must be needed to deliver community benefits. The Minister decides if a project is eligible.

NBE plans and the NPF will clearly outline information and notification requirements for resource consent applications. An Assessment of Environmental Effects will continue to be required as part of consent applications. These will be more targeted for controlled activities to manage anticipated effects and will likely be more comprehensive for discretionary activities where outcomes and effects are less certain.

The NPF and NBE plans will set notification requirements for applications and may specify affected persons for any activities that trigger consents. This will create certainty for applicants, iwi/hapū and Māori, stakeholders and decision makers. It will also reduce potential time delays and costs. The NBE plan or NPF can authorise consent authorities to make notification decisions and identify affected persons, in accordance with the provisions. Notification decisions by consent authorities will be able to be challenged in the Environment Court.

For substantive consent decisions, there is typically an appeal pathway to the Environment Court. In some circumstances, appeals to the Environment Court would be restricted if a regional alternative dispute resolution is used.

Resource consents will continue to play a critical role in the allocation of resources, including implementing new allocation methods specified in the NPF or NBE plans. During the transition period and before NBE plans are updated in response to allocation statements, shorter-duration consents for freshwater-related activities will be issued. This is to create a greater opportunity for NBE plans to effect change.

Designations will continue as the primary land-use tool for public infrastructure under the NBE Bill. The NPF and RSS will establish the high-level policy and framework for infrastructure. An RSS will integrate land-use and infrastructure decisions, including identifying indicative areas for new infrastructure over a 30-plus-year timeframe (eg, what is needed and why). The expectation is that these decisions are not revisited at the NBA level. Instead, for infrastructure identified in the RSS, the designation process under the NBE plan will focus more on ‘how’ the infrastructure is built and operated and the management of any environmental effects associated with this.

This will enable central government, local government, infrastructure providers and developers to make strategic funding and investment decisions and strengthen collaborative approaches to infrastructure provision.

Designation powers will be available to a wider range of infrastructure providers. Port operators (under the Port Companies Act 1988) will be able to designate for land based activities (outside the coastal marine area), and fire and emergency services will have automatic access to designation powers.

Other providers will be able to apply to the Minister for “public good” infrastructure, including for a specific project or purpose – for example, public housing.

Infrastructure providers that have access to designation powers (requiring authorities) will be able to secure the land for a designation through a stand-alone process, without needing to provide information about environmental management at the same time.

This approach enables requiring authorities to secure land for future infrastructure earlier and to protect that land from conflicting land use, without needing to provide detailed information about how the future effects of construction and operation of the infrastructure will be managed. This will enable better strategic planning and more cost-effective delivery of infrastructure.

Construction and implementation plans (CIPs) will be the planning mechanism that identifies the works required to construct the designated infrastructure. These will outline the measures to manage the impacts of construction and operation of the infrastructure in its physical surroundings. CIPs will be separated into Primary and Secondary CIPs.

Primary CIPs will identify the scope of the works and address the key matters requiring management to achieve the relevant outcomes. Primary CIPs will be notified and will provide opportunities for the public and other affected parties to participate in setting longer-term management measures. Primary CIPs will direct the matters to be considered in Secondary CIPs, which will include more detailed information for consideration by the RPC.

In the new system, infrastructure projects (corridors or sites) that are identified in the RSS will be deemed to be “reasonably necessary” for the purposes of the designations process. The spatial identification of infrastructure in an RSS will also remove the need for RPC to consider alternative sites, routes or methods for new designations, helping streamline and speed up the designation process and provide more certainty to infrastructure providers, landowners and the community.

The current system of allocation can be inefficient and favour existing users. The current system is characterised by first in, first served allocation, where access is based on assessing applications in the order in which they come in, and prioritising existing consent holders over other applicants when renewing their consents.

Under the RMA, it is possible for councils to develop allocation plans for scarce resources such as freshwater. However, the RMA only provides for those allocation rules to be implemented through first in, first served consenting provisions. In practice, this means that councils have been unable to develop fundamentally different allocation methods. Also, there has been a lack of direction from central government.

The NBE Bill includes an enabling framework for allocating resources, with specific provisions for freshwater, in natural and built environment plans (NBE plans).

This framework is designed to move toward a more deliberate and strategic approach to how resources are allocated. The current legal requirement for a first in, first served approach and the near automatic renewal of existing users when issuing consents will be updated for freshwater resources, as well as other resources where planning committees choose to apply the new framework and/or the NPF directs different approaches.

The new framework implements the Randerson Panel’s allocation recommendations and enables a range of allocation methods. Three principles of sustainability, efficiency and equity will guide the development of allocation methods, alongside other relevant provisions in the NBA and any detailed direction in the NPF. RPC will be required to have allocation plans applying the allocation principles.

Fractionalised land ownership and borrowing constraints have left much Māori land relatively underdeveloped. These allocation provisions will assist Māori, and others with underdeveloped land, to access water to develop their land.

The Government has committed to not precluding Māori rights and interests in freshwater in the resource management reform process. A preservation clause in the NBE and SP Bills records that assurances were made by the Crown to the High Court in 2012 regarding rights and interests in freshwater and geothermal resources.

The preservation clause makes clear that the NBE and SP Bills do not create or transfer any proprietary rights or interests or determine or extinguish any rights or interests that may exist.

The NBE Bill provides for the establishment of a Freshwater Working Group. It will provide recommendations on matters relating to freshwater allocation, and on a process for engagement between the Crown and iwi and hāpu, at the regional or local level, on freshwater allocation.

The NBE Bill will enable a wider range of allocation methods including comparative (merits based) consenting and more market-based allocation methods for some resources.

Comparative (merits based) consenting enables decision makers to compare competing applications against criteria based on merit. The order of lodgement does not affect decision making.

Market-based allocation methods will not be possible for freshwater takes and diversions. Pricing for water cannot be enacted without prior parliamentary approval. For other resources, market-based allocation methods, such as auction or tender, will be possible.

There will be no changes to the existing RMA provisions on charging for sand, shingle, shell and other natural materials, for occupation of marine/river space, and for geothermal energy. Payments of royalties for sand and shingle extraction to customary marine title holders will continue, consistent with rights under the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011.

Long consent durations are a practical barrier to moving away from first in, first served, although freshwater consent durations are becoming shorter – for example, the average length of freshwater take consents issued during 2021 in the Bay of Plenty, Canterbury and Southland were between 10 and 13 years. Many freshwater consents will expire during the transition to the new system.

There are two shorter-term consent proposals for freshwater takes and discharges.

Shorter-term consents under the RMA

Shorter-term consents under the NBA.

Shorter-term consents will be issued under the RMA for freshwater takes and discharges during transition to the NBA. These consents must expire within three years of the relevant NBE plan being notified. This is to create a greater opportunity for NBE plans to effect change, as well as preserve future options for more equitable access to freshwater resources for Māori and others with underdeveloped land.

There will be exemptions for some renewable electricity generation, reticulated water supply and the construction, upgrading or maintenance of specified nationally significant infrastructure. Existing users will still be prioritised when replacing an existing consent and can use a simplified consenting process.

Shorter-term consents will apply under the NBA until an NBE plan is updated with an allocation plan, informed by an allocation statement (if any) between the Crown and local iwi/hapū. These consents will have maximum durations of 10 years, with similar exemptions. In the long term, consent durations of up to 35 years will be possible.

Marine aquaculture is one of the primary uses of coastal space in some parts of Aotearoa New Zealand. The allocation of space for aquaculture and management of its environmental effects within the territorial sea (that is, out to 12 nautical miles) is currently undertaken under the RMA. Other aspects such as biosecurity, take of mussel spat, food safety and some impacts on fisheries are mainly managed under other statutes.

The future resource management system will have the same roles for aquaculture but a different toolbox for carrying out those roles.

One of the key outcomes of the reform for aquaculture will be more certain and efficient space allocation and consenting processes. This aims to promote investment confidence, provide for new opportunities (such as open ocean aquaculture) and enable the industry to adapt more readily to climate change, cumulative effects and biosecurity issues. A key focus is also ensuring the Crown can best deliver on its obligations under the Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004.

Related outcomes include integration of decisions on space allocation and related developments (eg, landing and processing facilities), ensuring environmental effects are appropriately managed, upholding takutai moana rights.

Achieving these outcomes relies on upfront planning undertaken through the RSS and NBE plan development, so full achievement of the intended approach will only come once NBE plans are in place. Aquaculture planning will need to be consistent with limits and targets in the coastal marine area set through the NPF.

Strategic spatial planning in the coastal marine area will occur as part of RSS preparation. RSS will set the strategic vision for aquaculture in regions for the next 30 years, which could include identifying how mu potential aquaculture growth is anticipated. RSS will look across both the land and sea, making connections between anticipated aquaculture growth and the land-based infrastructure required to service that growth. RSS can also ensure that the location of aquaculture is considered alongside other uses (eg, shipping and cables) and values (such as protecting marine mammals).

RPC will be required to consider the new space plan developed under chthe Māori Commercial Aquaculture Claims Settlement Act 2004. The committees will provide early notification of draft RSS content to the Minister to prompt engagement between the Crown and iwi to ensure the Crown's settlement obligations in that region can be meaningfully delivered in the future.

RPC will, through NBE plans, carry out detailed planning and zoning for aquaculture. The committees will have access to a range of tools for allocating space, including to address competition for space and Tiriti settlement requirements and to ensure effective use of space. The plan and consent processes will also address effects of aquaculture on the environment and other activities, and the plans can help protect aquaculture operations from the effects of other activities (eg, discharges that would affect water quality).

Central government will continue to have tools to enable the Crown to play a more active leadership role in aquaculture planning and allocation at a national or regional level. The Minister responsible for aquaculture will retain the ability to recommend regulations that amend plan provisions to achieve the Government’s objectives for aquaculture – including providing for aquaculture settlement obligations. This tool will be enhanced to enable that Minister to specify situations where they, rather than the regional council, would be responsible for allocating authorisations for aquaculture-related resources.

That Minister will also be able to apply a temporary stay on receipt of consent applications for aquaculture (either at their initiative or at the request of regional councils or RPC) in situations of high and competing demand, in situations where better planning controls for biosecurity are needed or in order to support aquaculture settlement.

Consents for aquaculture will continue to have a default minimum consent duration of 20 years, with some exceptions, to provide greater investment certainty for existing and new aquaculture developments. Maximum consent durations of 35 years will remain, in line with consent durations for other resources. Consent lapse periods for aquaculture will be brought into line with other activities so will be set at five years.

Several amendments are also proposed to the RMA to enable the outcomes sought by some of the proposed enhancements to existing aquaculture-specific provisions to be realised during the transition.

The future resource management system will be supported by a robust and effective regime for compliance, monitoring and enforcement (CME), which will be implemented by local government.

Proposed changes to CME include:

broadening the cost-recovery provisions for CME in the NBE Bill, allowing for costs to be recovered for compliance monitoring of permitted activities and investigations of non-compliant activities

reducing the risk of inappropriate influence or bias in compliance and enforcement decision making

a substantial increase in financial penalties, broadening the range of offences subject to fines for commercial gain and increasing the limitation period to two years

prohibiting the use of insurance for fines, infringement fees and pecuniary penalties

allowing consent authorities to consider an applicant’s compliance history in the consent process

providing for alternative sanctions to traditional enforcement action and providing for new intervention tools, including enforceable undertakings and consent revocation.

Oversight of the NBA and SPA will help ensure the system is being implemented as intended, that the legislation remains fit for purpose and that the objectives and outcomes of the system are being delivered.

Central government will play a stronger regulatory stewardship and operational oversight role in the new system. This will be underpinned by a requirement in the NBE Bill to develop a system monitoring, reporting and evaluation framework that covers both the NBA and SPA. The framework is expected to contain a range of indicators and metrics to enable consistent monitoring of key system performance indicators, track the implementation of the new system and assess progress against key environmental and development indicators.

The framework will provide a basis for government to report annually on the monitoring of the NBA and SPA system performance and to report to Parliament at least every six years with an evaluation of NBA and SPA operation and effectiveness. This monitoring and reporting will provide regular information on the implementation and effectiveness of the system and any changes needed as a result.

The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE) will be required to independently review and assess the quality and robustness of the Government’s evaluation report and to report any findings or recommendations to Parliament. The Government will be required to respond to the PCE’s independent review.

The PCE, along with other bodies like the Office of the Auditor-General, will continue to provide independent oversight of the system.

Ministerial powers of assistance and intervention will largely carry over from the RMA into the NBE and SP Bills. These include powers to:

investigate the performance of a local authority or RPC and make recommendations

direct a change or review of an RSS or an NBE plan

appoint persons to perform powers, functions and duties under the NBA.

A new power will be added to enable the Minister to direct RPC and local authorities to take action in certain circumstances. New powers will also provide the Minister with the ability to address unsatisfactory performance of RPC.

Once established, the National Māori Entity for te Tiriti monitoring will monitor how the resource management system is giving effect to the principles of te Tiriti. Reports will be provided to monitored groups, and responses required, to demonstrate consideration of and subsequent action from the Entity’s findings.

The new Acts will work together as a single integrated system. The intent of the new system is to shift the weight of activity to the planning stage – and to reduce the need to litigate RM outcomes on a consent-by-consent basis.

Consistent with this intent:

The NPF will guide the development of RSS and NBE plans.

RSS must give effect to provisions of the NPF (where this is explicitly stated).

RSS must otherwise be consistent with the provisions of the NPF.

RSS will guide the development of NBE plans.

RSS will have sufficient weight on NBE plans to avoid re-litigation of the decisions taken in the RSS.

NBE plans must give effect to the provisions of the NPF.

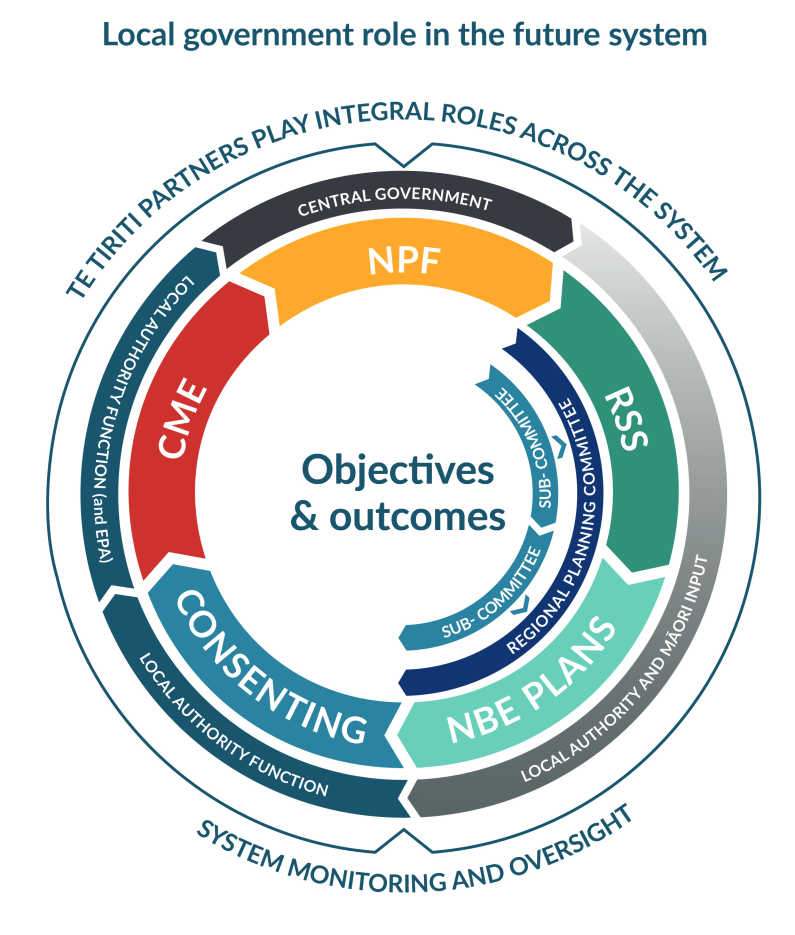

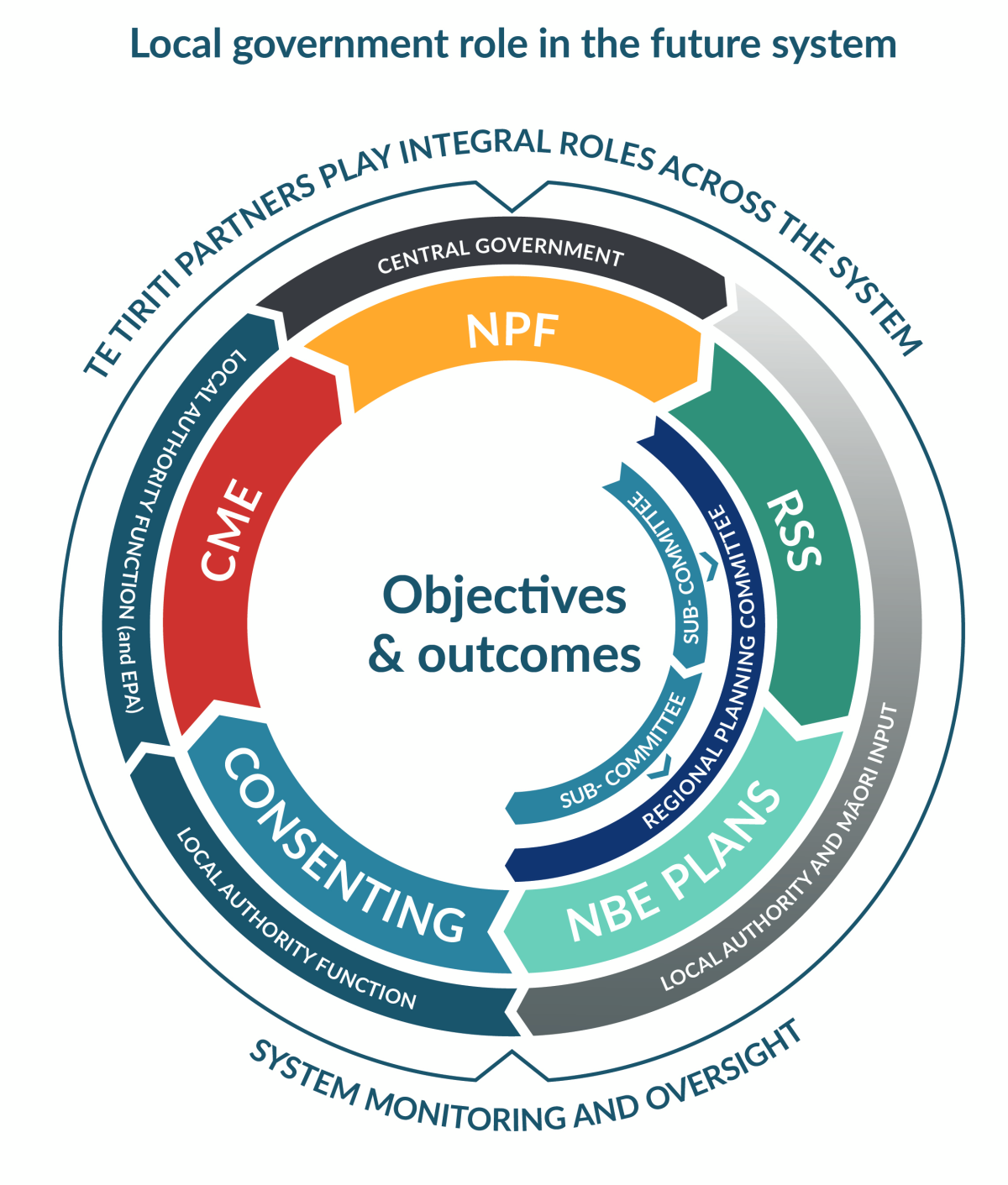

Regions will establish regional planning committees (RPC), which will include members appointed by local authorities and Māori in the region. For decision making on RSS, one member will be appointed by central government. RPC will make final decisions on RSS and NBE plans.

There will be flexibility in how RPC are formed, but there will be some minimum composition requirements. Each RPC will have a minimum of six members, with a minimum of two Māori members appointed through a Māori appointment process. Regions will be able to decide for themselves whether they want more members above these minimum requirements.

For local government, members will be appointed by the councils, with each territorial authority and regional council able to have a member on the RPC. For central government, the Minister will appoint one member to the RPC, who will join it for SPA matters only (with full voting rights).

Local government members may be an elected mayor, chair of a regional council, councillor, or any other person that a local authority agrees to appoint.

Iwi and hapū will lead the process to determine who will appoint the Māori members to RPC, engaging with iwi, hapū and other Māori groups with interests in the region.

Following engagement, iwi and hapū in the region will determine the Māori appointing body or bodies who will then make appointments to the RPC. Those Māori appointing bodies may take any form and may include the iwi or hapū themselves, a Māori group with interests in the region, such as a mātāwaka group, or a combination of iwi and hapū with other Māori groups with interests in the region.

Any appointments made under the Māori appointments process will be in addition to any required under relevant Tiriti settlements.

Each RPC will be supported by a secretariat, which will prepare advice for the RPC and develop a draft RSS and NBE plan, and support the RPC to make sure local communities are involved in developing the RSS and NBE plan.

An RPC will have flexibility to determine the working arrangements for their secretariat. Staff working in the secretariat may be employed or contracted by the secretariat, seconded to the secretariat from a local authority, or remain at the local authority and work collaboratively across the region.

The director of the secretariat will be able to bring in any technical skills needed, and the secretariat will need to have expertise in local kawa, tikanga and the mātauranga of the iwi and hapū in the region.

RPCs will also have flexibility to establish sub-committees to focus on particular matters or for a sub-region.

They will be required to establish at least one sub-committee for freshwater to make recommendations on the freshwater component of the first NBE plans. These freshwater sub-committees will be comprised of members nominated by regional councils and Māori appointing bodies.

This section sets out the roles and responsibilities for the main decision makers in the system.

Local government

Central government

Hapū/iwi and Māori

As the key institution in the new system, local government will continue to have critical roles in implementing the future resource management system. Local government will continue to shape our regions, cities and districts through the strategies and plans they will develop together. Local government will work with central government and Māori on an RPC to identify how the region will grow, adapt and change over the next 30-plus years.

Local authorities will:

play an essential connecting role between local communities and RSS and NBE plan development

support effective community engagement processes to ensure RSS and NBE plans enable local place-making and will give effect to significant views through governance and decision-making arrangements

contribute to RSS and NBE plan development, including through provision of information, resource and expertise (nb, involvement of councils through the secretariat will provide an avenue for council input into drafting)

provide local plans to inform strategy and plan development, with the NBE Bill providing for place-shaping documents, such as local plans, under the Local Government Act 2002 (eg, town centre plans, community plans)

lead the development of statements of community outcomes and statements of regional environmental outcomes, which will be an important contribution to the development of the RSS and NBE plans

support engagement with local communities on strategies and plans, collaborating with hapū/iwi/Māori and building on existing relationships

review and provide feedback on draft strategies and plans.

Local government will continue to be the key institution to implement our future resource management system.

Regional councils will retain responsibility for natural resource functions, and territorial authorities will retain their core land-use and subdivision responsibilities.

Local authorities will implement RSS through their plans and functions under the Local Government Act 2002 and through implementation plans and agreements under the SPA. They will continue to be responsible for consenting.

Local authorities will continue to be responsible for compliance, monitoring and enforcement, including deciding when to take enforcement action. Local authorities may be required to provide consistent and regular local-level environmental reporting and would likely have roles in monitoring the implementation of RSS and regulatory instruments under NBE plans.

Central government will have a more active role in the resource management system, with stronger system stewardship and participation at the strengthened regional level.

This includes:

the Minister providing greater national direction – having responsibilities for the NPF, along with powers to ensure that it is fully implemented through the RSS and NBE plans (eg, by directing that changes to these are made to give effect to provisions in the NPF)

the Minister being responsible for setting limits and targets (including prescribing any requirements for planning committees to set them in plans)

a more active role in the regions through appointments to RPC for the development of RSS

bringing together central government agencies to engage with the SPA process and be the “voice” of central government. Having this one touchpoint will enable more effective engagement with central government, addressing a frustration of local government that central government can be hard to pin down

communicating central government priorities when developing RSS, being part of the decision-making process for RSS and actively supporting their implementation through implementation plans and agreements

engaging with iwi/hapū at a local level on matters of freshwater allocation

having key responsibilities in monitoring, reporting, evaluating and responding to the performance of the system

playing a stronger role in providing oversight of the system, including more active participants (and therefore identifying issues earlier) and undertaking formal monitoring. Oversight will also be provided at a national level by independent bodies such as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment and the proposed National Māori Entity

providing support for the transition to and implementation of the new system, including through supporting development of digital tools and supporting the first tranche of regions to develop their RSS and NBE plans.

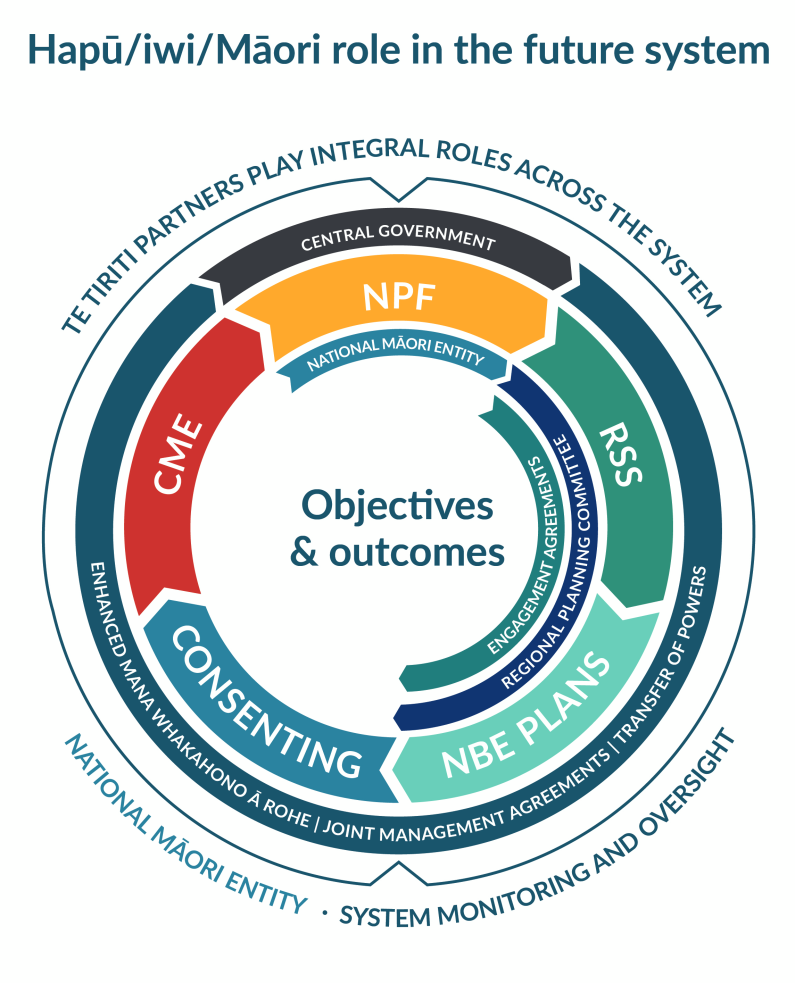

The new system will improve on the RMA by providing for more effective roles for Māori and by requiring decision makers to give effect to the principles of te Tiriti, rather than just take them into account. Introducing this requirement means that Tiriti principles will be considered and implemented across all decision making under the NBA and SPA.

Proposals for the allocation of freshwater resources are outlined on page 37.

It is proposed that a National Māori Entity be established to have a specific role in monitoring Tiriti performance, providing input into the NPF and more broadly advising people in the resource management system. The National Māori Entity will be an independent statutory entity and will operate independently of the government of the day. The Entity will be able to choose its own name. The Entity will provide an additional voice on Tiriti performance but will not replace the need for central and local government to engage with iwi/hapū/Māori in their area on resource management matters.

The National Māori Entity is to be set up in a way that does not usurp the mana of hapū, iwi and Māori in an area.

In more detail, the National Māori Entity will:

monitor and assess whether the resource management system is giving effect to the principles of te Tiriti (with reports provided to monitored groups, and responses required, to demonstrate consideration of and subsequent actions from the Entity’s findings)

provide direct input into the development of the NPF, using its insights and findings from Tiriti performance monitoring

have the opportunity to nominate members to be considered for appointment to the NPF board of inquiry and will have the right to be heard at the board of inquiry hearings

provide advice to those in the resource management system, either proactively or on request

be consulted by the Chief Environment Court Judge when the Judge is making appointments to Independent Hearing Panels (IHPs) as part of the NBE plan development process (noting that nominations of members to IHPs will be determined by those representing the regions). It is intended that Māori will determine membership of the National Māori Entity. Details on the appointments process are currently being worked through.

At a regional level, Māori will have roles and functions in the creation of RSS and NBE plans. Māori will appoint members to each RPC. The process for Māori appointments will be self-determined by Māori and be led by iwi and hapū in the region.

Engagement agreements is a new tool that will provide a straightforward way for iwi, hapū, customary marine title group holders and other Māori groups to agree with the RPC on how they will be engaged in the development of RSS and NBE plans.

The engagement agreements recognise that while many councils have formal relationships with Māori already, the RPC are a new form of collaborative governance, and the agreements will be useful to clarify engagement expectations on the RSS and NBE plans and how this engagement will be funded.

e will be a requirement for a minimum of two Māori members on each RPC.

Existing tools under the RMA – such as Mana Whakahono ā Rohe, transfers of powers and joint management agreements – will be maintained and enhanced in the NBE Bill, including enabling hapū to be party to these tools. Legislative barriers to their uptake will be removed, and positive obligations will be added for RPC and councils to investigate their use.

These tools will enable local flexibility in relationships between hapū, iwi, local authorities and RPC.

Existing Mana Whakahono ā Rohe, transfers of powers and joint management agreements will continue and be upheld in the new system.

There are issues in relation to Māori land in the current resource management system, such as barriers to the ability to use and develop Māori land beyond those that apply to general land. Māori land is subject to Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993. It is a taonga tuku iho of cultural importance and is often held collectively (with the average Māori land block having 111 owners).

Consideration is required for Māori land across a range of matters to recognise the unique ownership, legal and practical characteristics of this land.

Specific provisions proposed for Māori land include direction to be provided in the NPF to facilitate enabling approaches for non-commercial housing and papakāinga on Māori land, protections for Māori land in the designations framework and requiring Māori landowner consent before placing heritage protection orders on Māori land.

The system is designed to encourage broad engagement with both RSS and NBE plan development to ensure an RPC has access to good information and understands the perspectives of all parts of the community.

The RPC will be required to develop and notify an engagement process under the SP Bill, with the committee having the flexibility to determine how this is done. The SP Bill contains some key outcomes that must be achieved and basic steps that must be included, such as early engagement with key parties and the public.

The RPC is expected to consider how best to encourage effective input from the region, using a range of tools and approaches. This could include different engagement approaches for different issues, parts of the community or parts of the region.

A key step in the engagement process will be notification of a draft RSS, with a call for written submissions. The RPC may decide to hold hearings for all or part of the RSS.

The SP Bill does not provide for appeal rights, but judicial review will be available to those who consider the RSS process or content was not consistent with the requirements of the Act.

The RPC will be able to amend the RSS, including if issues are encountered in translating the provisions into the NBE plans. The level of engagement for any amendments will vary, but significant changes that are not required by the NPF will require preparation of an engagement process.

Developing an NBE plan will follow preparation of an RSS. Each RPC will seek input from local communities, Māori, infrastructure providers and stakeholders. NBE plans are intended to have a strong local voice. Early engagement will be encouraged, and parties who wish to contribute to the plan development process can register to engage in the process.

A new feedback process called “Enduring submissions” will be introduced to allow submissions to be lodged before plan notification and throughout the plan hearings process.

Statements of community outcomes (SCOs) and statements of regional environmental outcomes (SREOs) are proposed as voluntary instruments to provide local authorities with a mechanism to directly input a local voice into NBE plans. The public will have the opportunity to contribute to the SCOs and SREOs

After the plan development phase, the RPC will notify, hear and make decisions on an NBE plan. Any person or entity can make a submission. Submitters must provide full information and any supporting evidence when they file their submission.

The hearings process for NBE plans will be run by an IHP.

Limits will be placed on subsequent appeals. Where an IHP recommendation is accepted by the RPC, appeals are limited to points of law in the High Court. Where an IHP recommendation is rejected, merit-based appeals can be made to the Environment Court. There are limits on bringing any new evidence to the Environment Court that was not provided in the earlier IHP process.

The new consenting system will still enable public participation for certain consent applications. NBE plans and the NPF will state which activities cannot be notified and which require full or limited notification – applications with more significant effects being open to submissions. However, NBE plans and the NPF may also specify that no party needs to be notified as the effects are generally known. The Environment Court will be able to review councils’ notification decisions.

A supplementary analysis report (SAR), which considers the regulatory impacts of the SP and NBE Bills has concluded that Cabinet objectives for the new system can be achieved. The cost-benefit analysis in the SAR provides a strong, positive indication of the value the new system can deliver. Conservatively, the monetised benefit-cost ratio is 2.58, but realistically could be around 4.90. Large non-monetised benefits could also be realised, including for the natural environment.

To ensure a successful transition to and implementation of the new system, we need to ensure our partners and stakeholders can transition to and successfully participate in the new system. The new system will require shifts in how we work across local government, hapū/iwi and Māori, central government and stakeholders.

The Ministry for the Environment (the Ministry) has work underway to support the transition to and implementation of the new system.

The objectives for transition and implementation are to:

have the necessary measures in place to ensure transformational change in the resource management system

provide as much certainty as possible through transition for system users and implementers

enable iwi/hapū and Māori to effectively participate as partners in the new system and to enable te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori to guide transition and implementation of the new system

maintain and strengthen system integrity and stewardship

transition and implement the system in an efficient and effective way, focused on reducing complexity and partnering for success.

The current transition and implementation work programmes are described below.

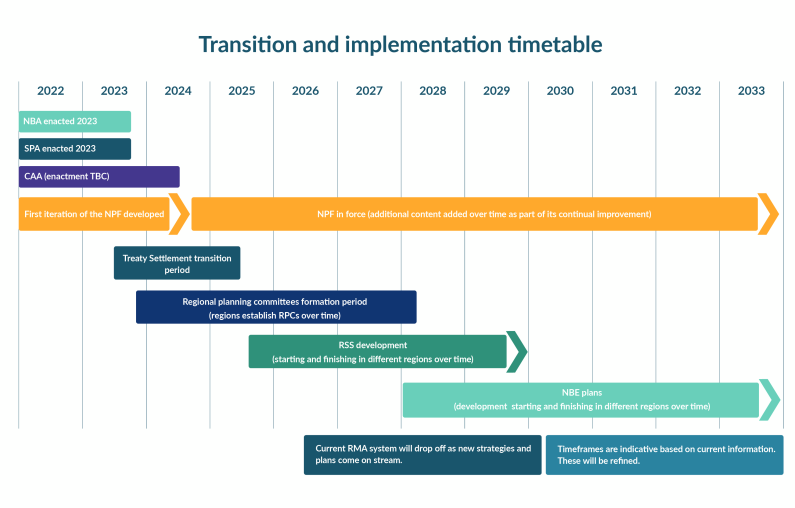

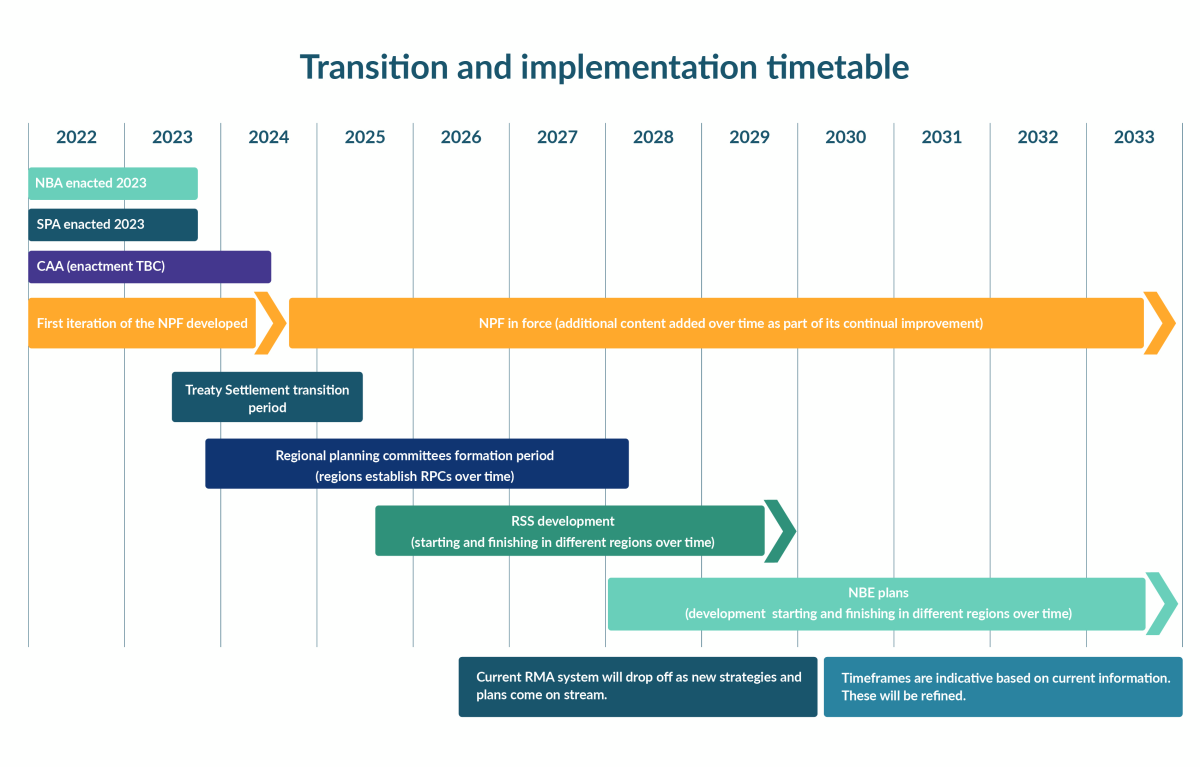

The transition to the new resource management system is expected to take about 10 years before there is a complete national application of the Spatial Planning Act (SPA) and Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA). This timetable was indicated in the Randerson Review Panel report and is largely driven by the need to ensure that the hierarchy of direction and guidance from the National Planning Framework (NPF) to RSS and natural and built environment plans (NBE plans) is achieved.

A staged approach is anticipated, whereby three regions will begin the regional spatial strategy (RSS) development process, followed by another group of regions 12 months later. Statutory deadlines for several steps can be set via secondary legislation (eg, a deadline to establish a regional planning committee (RPC) and a deadline to notify an RSS for public submission). A backstop date for RSS notification is set at seven years after enactment if an earlier date has not been set in secondary legislation. The NBE plan development timeframe is prescribed at four years, and this four-year period must commence within 40 working days of an RPC adopting their RSS.

To support the first RSS and NBE plans, the Government will support a “model project”, which will consist of the first regions to develop the strategies and plans in the new system.

The model project aims to provide guidance and support t these regions as they establish their regional planning committees and develop their strategies and plans. Working through these first plans will test and demonstrate the workability of the new system and provide learnings for the regions that follow.

Many detailed commencement, savings and transitional provisions are not included in the Bills. However, Government policy decisions for these provisions have been taken and some of the key decisions are summarised under the sub-headings below.

Various parts of the NBA will come into effect at different times and will replace Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) provisions through a staged approach. The staged approach will enable new RSS and outcomes-based NBE plans to be in place before any resource consents are considered under the new legislation and to ensure the current resource management system can continue to operate with minimal disruption.